Eating Oregon’s dulse can save the world

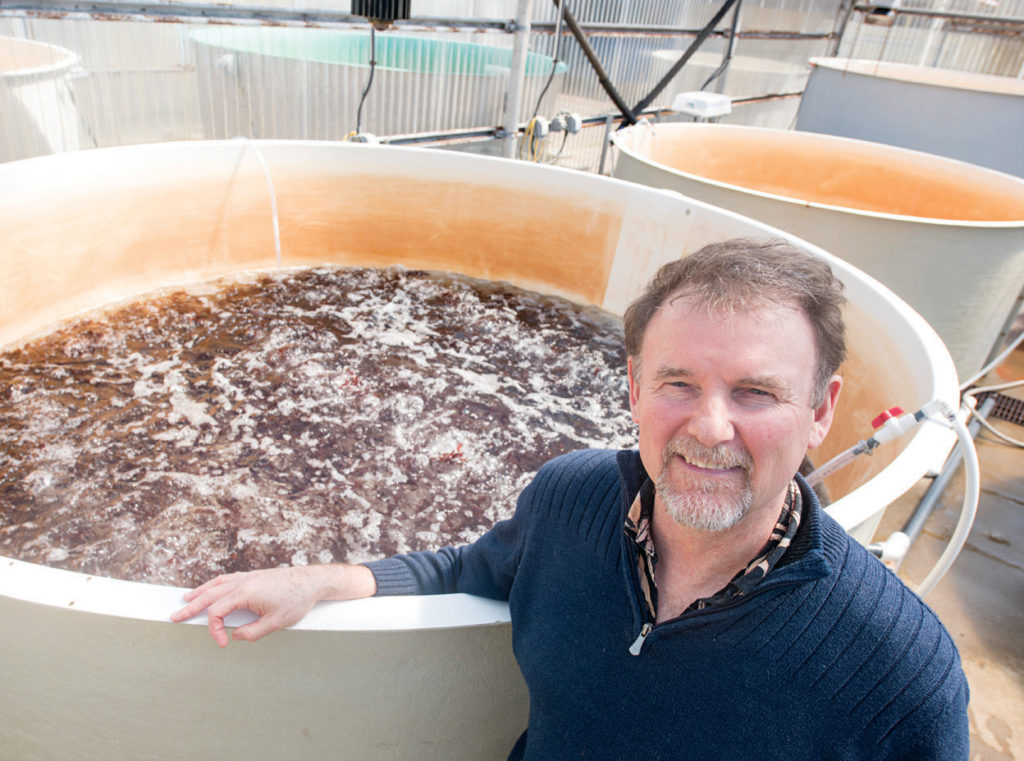

True, you might not be interested in eating a clump of seaweed. When you’re hankering for a hefty meal, a red alga poking about in the tide might not be what you had in mind. It’s often called a weed, after all, and who wants to eat weeds? But there are particular strains of seaweed called dulse that you might want to consider. Patented in the labs of Oregon State University, under the guidance of professor Chris Langdon, who has specialized in aquaculture for decades, and promoted by Chuck Toombs, an entrepreneur who is part of OSU’s School of Business, dulse is something you should really get excited about.

You’re not excited yet. It’s seaweed. But why can’t dulse be the new kale? It’s high in protein, provides natural iodine, has twice the potassium as a banana, has all the amino acids a body needs, and it’s chock full of antioxidants, B12 and more. Here’s the thing: It tastes like bacon when fried. Yes, bacon, and some of the world’s leading plant-based meat substitute companies are quite interested in the dulse being created in Oregon. So, too, is the World Bank, along with environmentalists. There is more to this seaweed.

You can grow more dulse in a smaller area than you can, say, soybeans. It’s also more environmentally friendly than soybeans in that you don’t need soil, pesticides or fertilizer. Dulse grows quickly in recirculating aquaculture tanks, which means that it can be a part of the solution to feeding our rapidly increasing global population.

There is more about dulse to tout. It eats carbon. It’s a negative carbon protein. That is to say, if you were to have a 20-square-mile seaweed farm in the middle of Oregon somewhere, the state would become a carbon neutral state just by all the carbon being sequestered by the dulse. “The more you eat of this stuff,” Toombs says, “the better the world is.” Langdon concurs. “It’s not only good for humans to eat, it’s good for the world.”

In Langdon’s labs at OSU’s Hatfield Marine Science Center, he has been focusing primarily on molluscan shellfish, marine fish larval nutrition and sea vegetables. He was working on creating a super-food for abalone, a delicacy in many parts of the world, particularly East and Southeast Asia. He started growing dulse as that super-food, and the abalone that fed on that dulse grew at rates that exceeded all known abalone at the time. He was onto something.

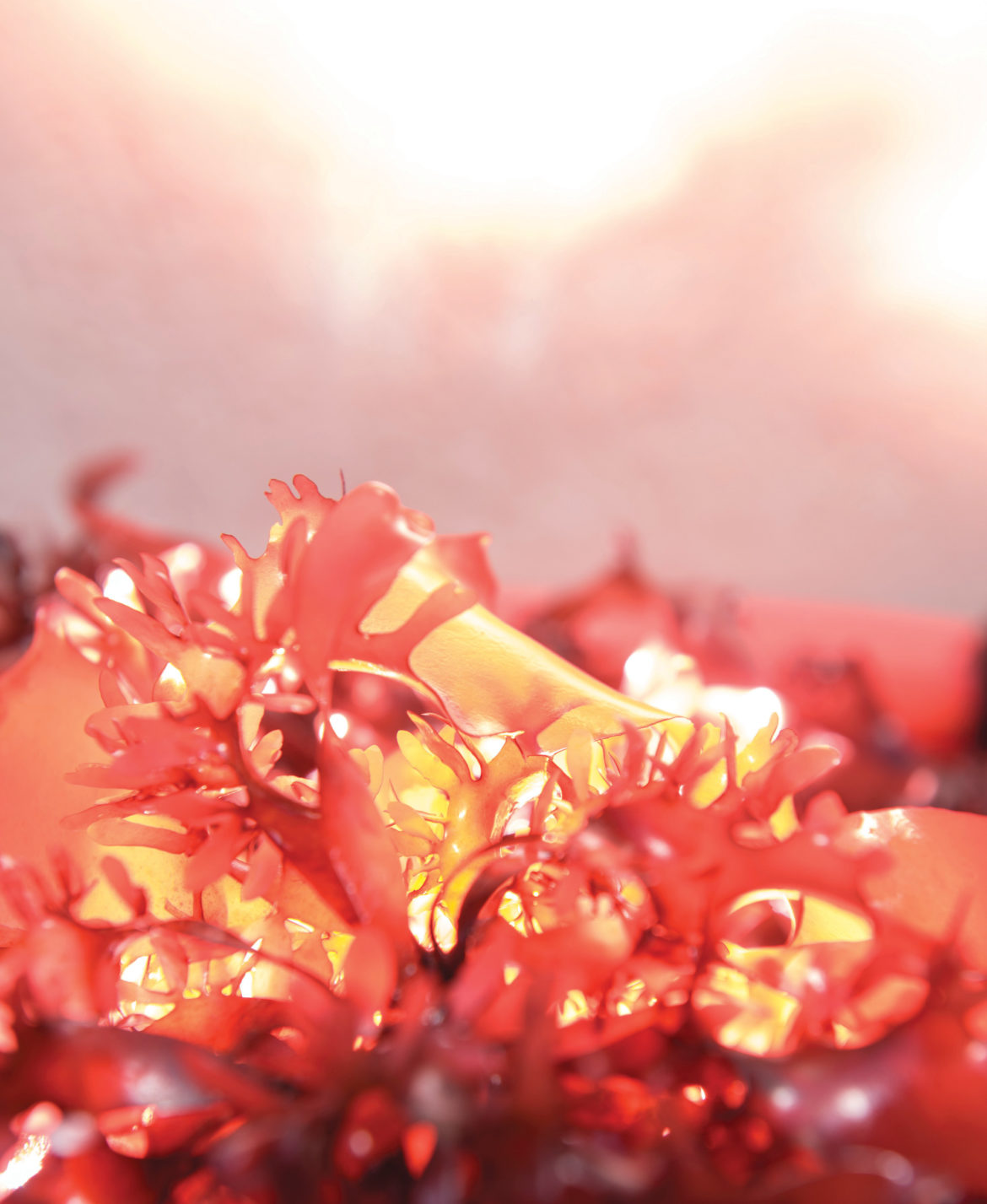

Dulse, palmaria palmata, is a seaweed that grows along the Pacific Coast and elsewhere. It has a burgundy-like color. Neither Langdon nor Toombs were the first to understand dulse’s possibilities as a food source. The earliest known record of dulse was on the island of Iona in Scotland. Christian monks were harvesting it for consumption some 1,400 years ago.

Toombs happened by Langdon’s lab at the college. A light-bulb went on over his head. Oregon Dulse was launched. Dulse grew quickly. It was high in protein. It didn’t take much room or resources to grow. It was also being sold, dried, at nearby specialty grocery stores for more than $90 per pound. “Why can’t this be the new kale?” he asked. It was Gwyneth Paltrow, Toombs notes, who was touting kale across media outlets. “But kale tastes terrible!” Toombs said.

There are now two land-based dulse farms in Oregon, with a proposed third 30-acre farm coming into fruition. It may become the largest land-based seaweed farm in the world. Brandon Farm opened in 2018. A farm in Garibaldi opened in 2020.

Oregon Dulse caters to restaurants. Protein processing facilities are being made to cater to companies making plant-based substitutes for meat products. Perhaps soon the hefty burger you crave will be dulse based. Oregon Dulse is also looking at carbon markets. “If a company says they’ll be carbon neutral within such-and-such a time, how can they accomplish that?” A dulse farm could help,” Toombs said.

“There is a lot going for it,” Langdon said. “It doesn’t need fresh water. It removes carbon dioxide. It’s a rich protein source. It’s fast growing with high yields. It’s why I’m very enthusiastic about dulse being a great sustainable food source for us all.”

Toombs, Langdon and others are eager to see where these seaweeds lead. They’ve gotten help. They have won grants from the Oregon Department of Agriculture. Portland’s Food Innovation Center has conducted its own research done on the culinary side of dulse. T Katapult Ocean, the world’s largest ocean impact accelerator, is investing. All the better that it tastes like bacon.