For one wild month, Woody Guthrie was paid to write songs about the Pacific Northwest

written by Isaac Peterson | photos courtesy of the Bonneville Power Administration

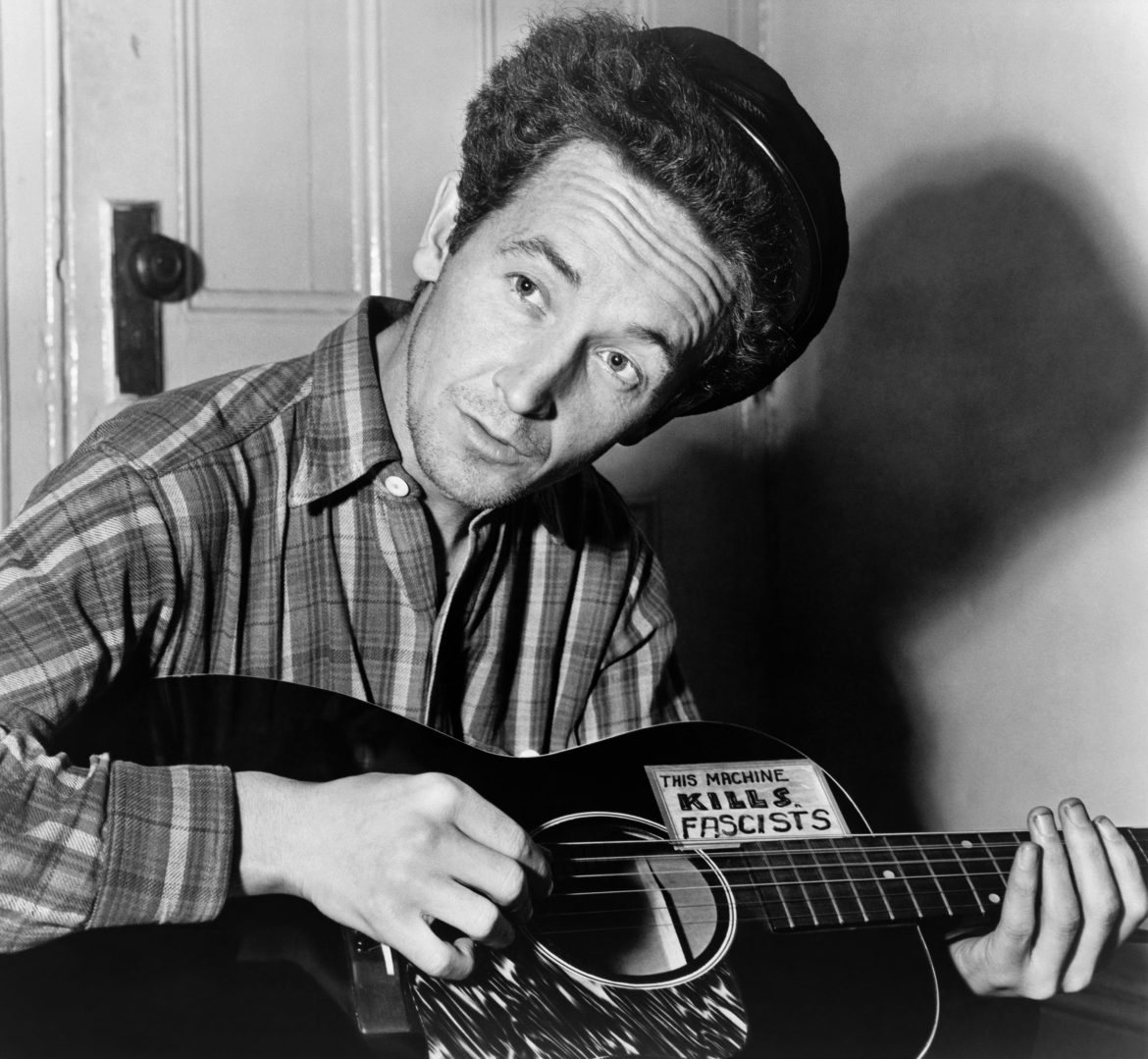

Biographies of Woody Guthrie sometimes include the footnote that he visited Oregon for a month in the spring of 1941 and wrote a few songs about the Pacific Northwest during his brief stay, notably “Roll on, Columbia.”

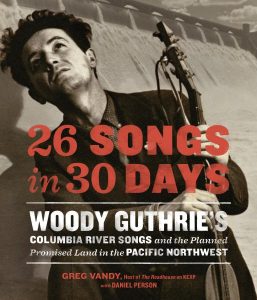

New research by Bonneville Power Administration Library & Visitor Center archivist Libby Burke and 26 Songs in 30 Days, a book by Greg Vandy, reveal Guthrie’s month-long sojourn in the Pacific Northwest was more than just a footnote to his art and legacy. It may have been the folksinger’s defining moment.

The story begins sometime in the early ’80s when Bill Murlin was reviewing an old 16mm film in the Bonneville Power Administration’s media office in Portland. The film, called “The Columbia,” had been completed by the BPA in 1948 to communicate the benefits of hydroelectric power. It was unusual for a government informational reel. Director Stephen Kahn’s luminous black and white photography, set to a sweeping score of orchestral music and folk songs, revealed the Columbia River as the living heart of the Pacific Northwest. Murlin knew he had found the centerpiece for the anniversary celebration.

When the credits began to roll, Murlin had a moment of revelation that must have been akin to discovering a Renaissance masterpiece at a garage sale: Woody Guthrie was credited as the songwriter. Murlin was an accomplished folksinger in his own right, and his curiosity was piqued. He knew federal processes would have required Guthrie to work as a salaried employee in order to join the project. Had Guthrie worked for the federal government under the auspices of the Bonneville Power Administration? If so, what were his job responsibilities? The songs used in the film were well-known and included “Roll on, Columbia,” but Murlin guessed that learning the details of Guthrie’s work on the film might reveal new songs no one had heard. Guthrie was an incredibly prolific songwriter, creating more than 1,400 songs in his lifetime.

Murlin called the U.S. Office of Personnel Management and learned Guthrie had indeed been a salaried employee and what’s more, the office had his employment records—in a cardboard box trundling down a conveyor belt to the in-house industrial shredder. Should they pull them from the line if they hadn’t yet been destroyed?

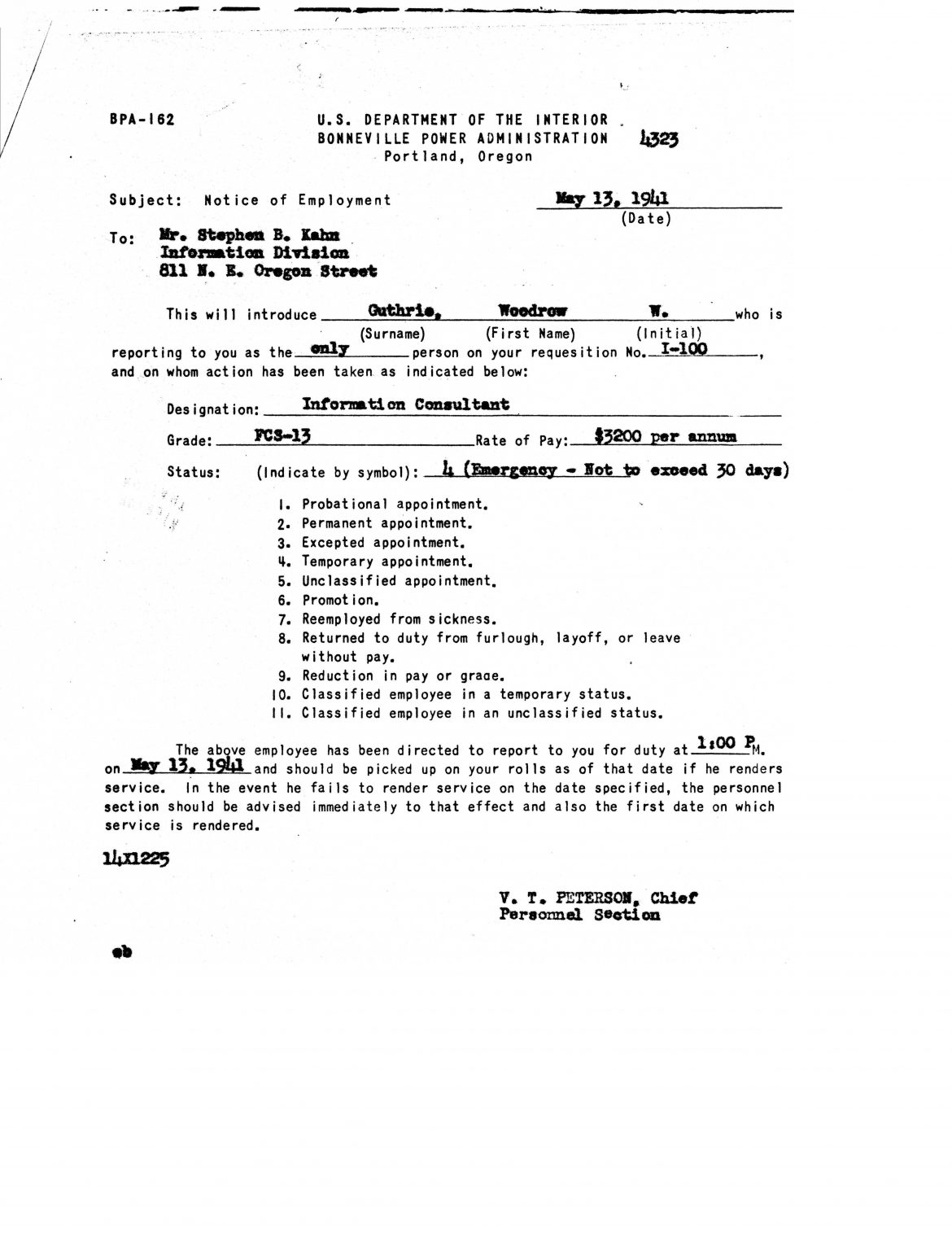

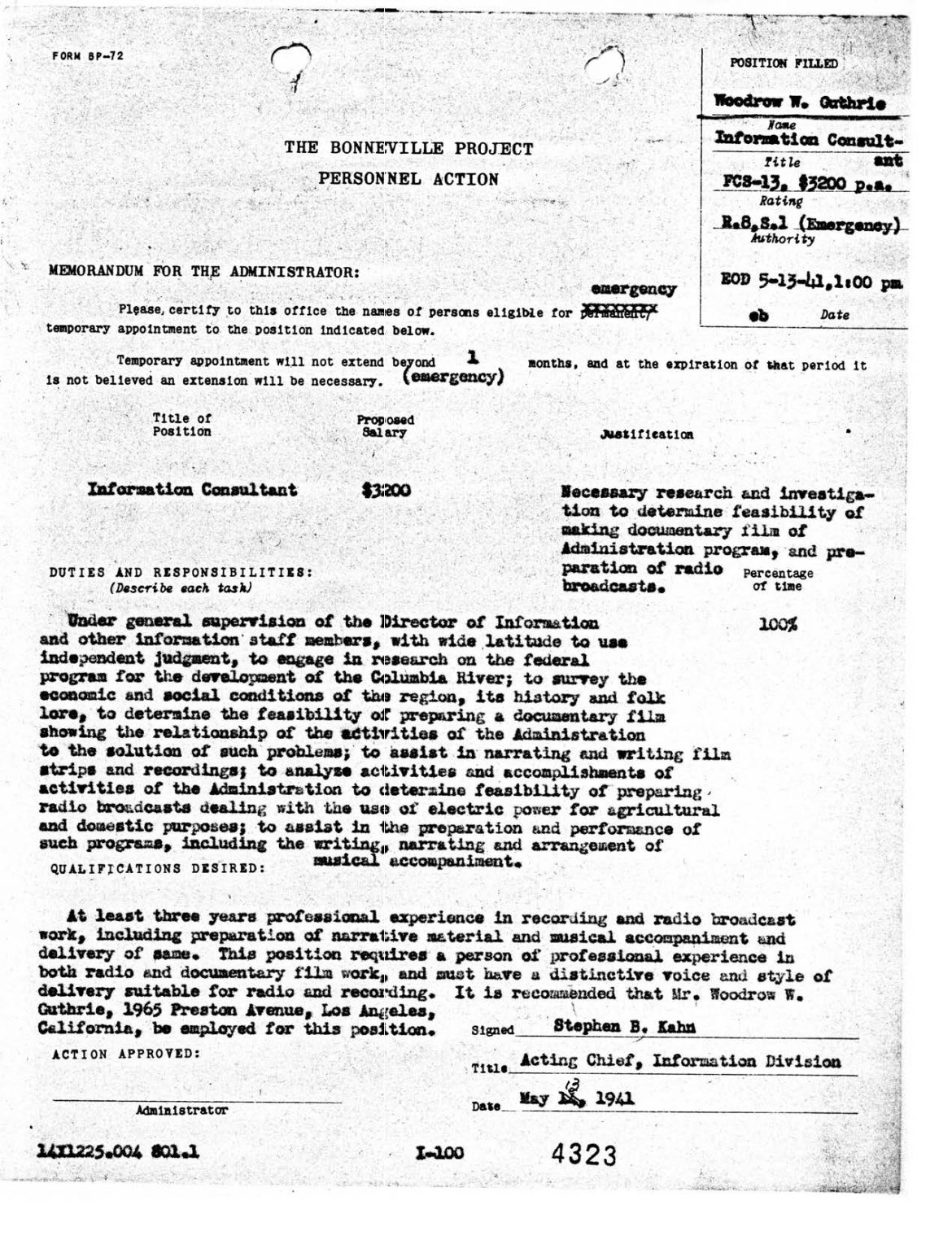

Guthrie’s federal employment documents, rescued by Murlin from the shredder, tell a strange story. In early 1941, Stephen Kahn was a BPA filmmaker who wanted a relatively unknown folksinger, Woodrow Wilson Guthrie, to write music for his new informational film on the benefits of hydroelectric power that had been commissioned by the government. Working from his Portland office, Kahn carefully navigated the labyrinth of budget requisitions and federal approvals he would need in order to get a salaried line-item for a songwriter.

By April 1941, Guthrie was nearly destitute. He had abruptly left his job at a radio station in New York, refusing on principle to sing what the advertisers wanted, and had dragged his young wife and three children across the country to L.A. Desperate and running out of money, he decided to deliver documents to Kahn in person at the BPA offices.

“He just showed up at the door of the BPA in Portland, looking for the job he’d heard about,” archivist Libby Burke said. “He was living in extreme poverty with his family, and just the possibility of a job was better than their life in California.”

Kahn took Guthrie into the office and set up an emergency appointment for the folk singer. The emergency appointment process was a way of mobilizing extra resources in times of natural disaster; Kahn had used it to employ a destitute musician from Oklahoma. Guthrie’s term as “information consultant” was thirty days. Guthrie was required to account for his hours every day, so he decided to simply write one song a day, returning to the Portland office every evening to type up the lyrics on a typewriter and dutifully perform the music for a wax-cylinder recording device.

Woody Guthrie in Oregon: A song a day

He was supplied a car and a chauffeur and every day drove along the path of the Columbia, looking out at the countryside, the Grand Coulee Dam and the Bonneville Dam, talking with rural farmers whose economic outlook had radically improved because of hydroelectric power, drawing and writing songs. In the afternoon, he’d work out his compositions on guitar and then return to the office to record and transcribe them.

Kahn’s emergency intervention had given the tumbleweed troubador a brief respite from his troubles, and provided a modicum of stability for the Guthrie family in the little apartment they had rented on Portland’s Southeast 92nd Street.

In Guthrie’s stormy life it was a month of calm and security. The verdant land surrounding the Columbia in the gentle warmth of spring seemed like Eden, and during this time he wrote a song that many view as his masterpiece: “Pastures of Plenty,” about poor migrant farm workers leaving Oklahoma to look for work picking fruit in the Pacific Northwest.

It’s clearly drawn from Grapes of Wrath, a book Guthrie read for the first time in Portland (Kahn had given it to him), but the fact that he wrote it while tromping around Oregon in the springtime reveals the masterpiece in a new light.

He’s using what he learned from his time with the migrant workers in California,” Burke said. “In the song ‘Pastures of Plenty,’ he’s also singing about the Pacific Northwest. He’s singing about the part of the country that we live in. The pastures of plenty are real, and the hope in that song springs out of the hardships that working people endured, that brought them here for a chance at a better life.”

Guthrie left Portland three days early thanks to vacation days he’d earned as “information consultant.” He picked up his check and hit the road—without his wife and family—and his first marriage had disintegrated by the time he hitchhiked back to New York. Back in New York he joined the Almanac Singers, then served as a Merchant Marine in World War II. In the ’50s he was diagnosed with Huntington’s Disease, a fatal genetic brain disorder that left him without the ability to speak for fifteen years before his death in 1967.

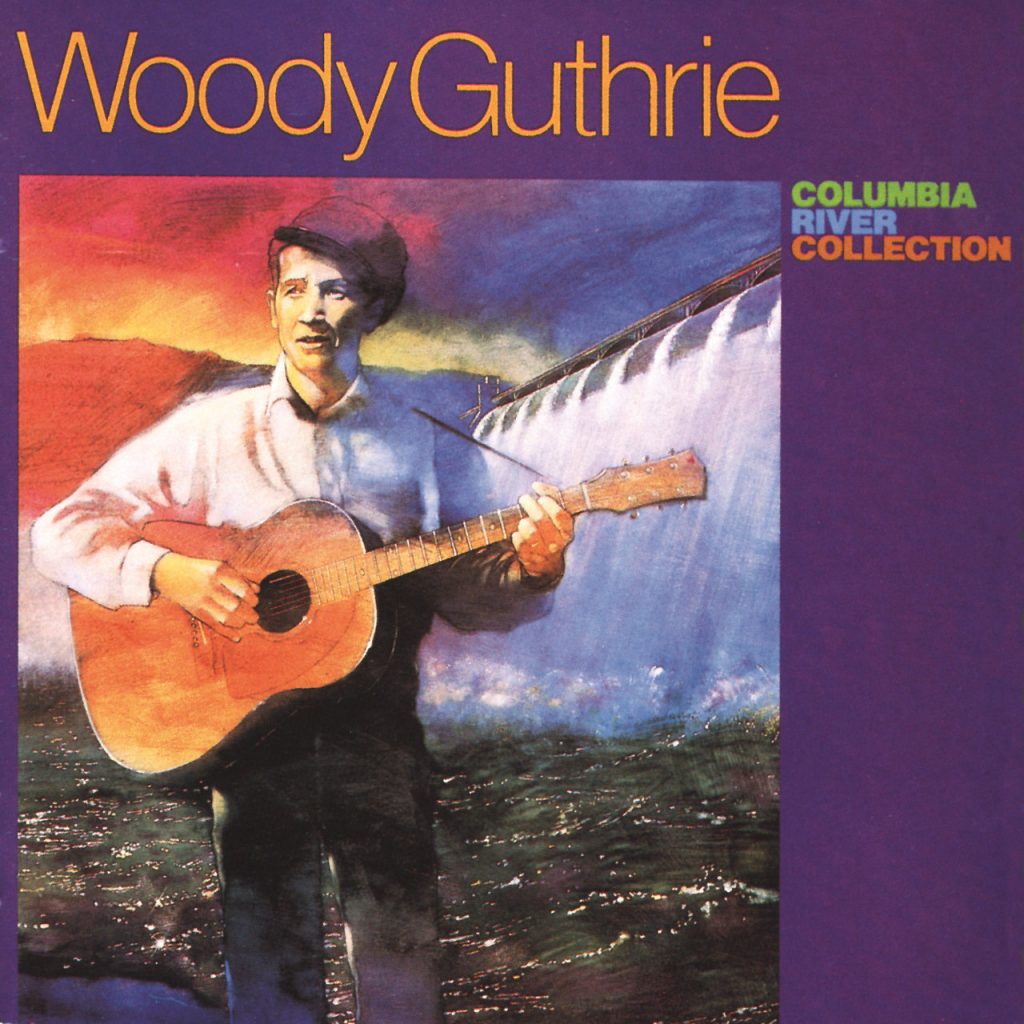

Years later, when Murlin found a letter from Guthrie noting he had written twenty-six songs for the government, he set out to find them. An article on Murlin’s discovery sparked a nationwide search for the missing songs, which would become known collectively as the Columbia River Songbook. Guthrie’s original wax cylinders he’d recorded at the Portland office were long gone, but every day Murlin unwrapped packages sent to him from dusty New York attics, forgotten studio archives, and the storage spaces of Guthrie’s friends and relatives. Gradually Murlin found all the songs. The BPA, in collaboration with The Smithsonian and The Woody Guthrie Center in Oklahoma, released the Columbia River Collection in 1988 with an accompanying book of music called the Columbia River Songbook.

In 2017, Murlin released a new edition of the songbook to honor the seventy-fifth anniversary of the Columbia River Songs. Along with Joe Seamons, he created a new recording containing all twenty-six songs for the first time, sung by Northwest artists.

Best Oregon Summer Trips: Our Top 25 Travel Destinations in Oregon