Written by Ben McBee

It’s hard to think of something that evokes the spirit of Oregon more than the rain. We have it to thank for lush evergreen forests and roaring waterfalls. One of the state’s largest companies, Columbia Sportswear, made a name for itself protecting its consumers from the iconic Pacific Northwest drizzle. The dreariness has even inspired Portlandia skits.

With all the precipitation it witnesses, it’s not surprising that Oregon has experienced calamitous floods. There was the Willamette Valley Flood of 1996, which caused more than $500 million of damage, the Vanport Flood in 1948, which wiped an entire neighborhood off the map, and the Christmas Flood of 1964, which killed nineteen people, destroyed parts of twenty major highways and ruined hectares of agricultural land—earning it the “Thousand Year Flood” title.

Incredibly, those three deluges occurred after modern flood control measures had been put into place in the form of dams at sites like Detroit Lake and Cottage Grove Reservoir.

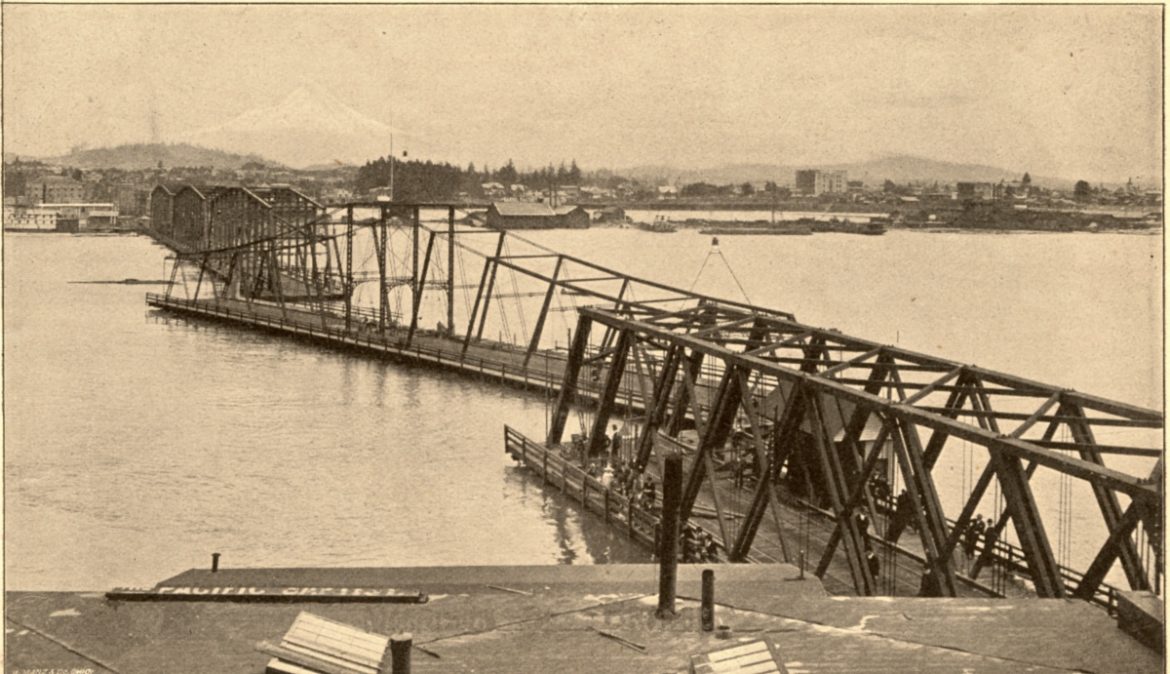

As devastating as the more recent disasters were, the waters of the Willamette River have never risen higher than they did in June 1894. Turn-of-the-century Portland sprung up as a vital economic hub due to its position at the confluence of the Columbia and Willamette rivers, a location that could be precarious when torrential rains fell. Severe spring snow melt and summer downpours combined that year to push the river deep into downtown, setting a record 33-foot high watermark that still stands today.

The Flood

As you walk through Old Town, past the long line for Voodoo Doughnuts and the tome-lined columns of Powell’s, it’s hard to imagine what such intense flooding would look like. Thanks to a burgeoning interest in photography at the time, we don’t have to wonder. The resilient and probably soggy Portlanders produced thousands of images depicting how daily life changed when streets became canals.

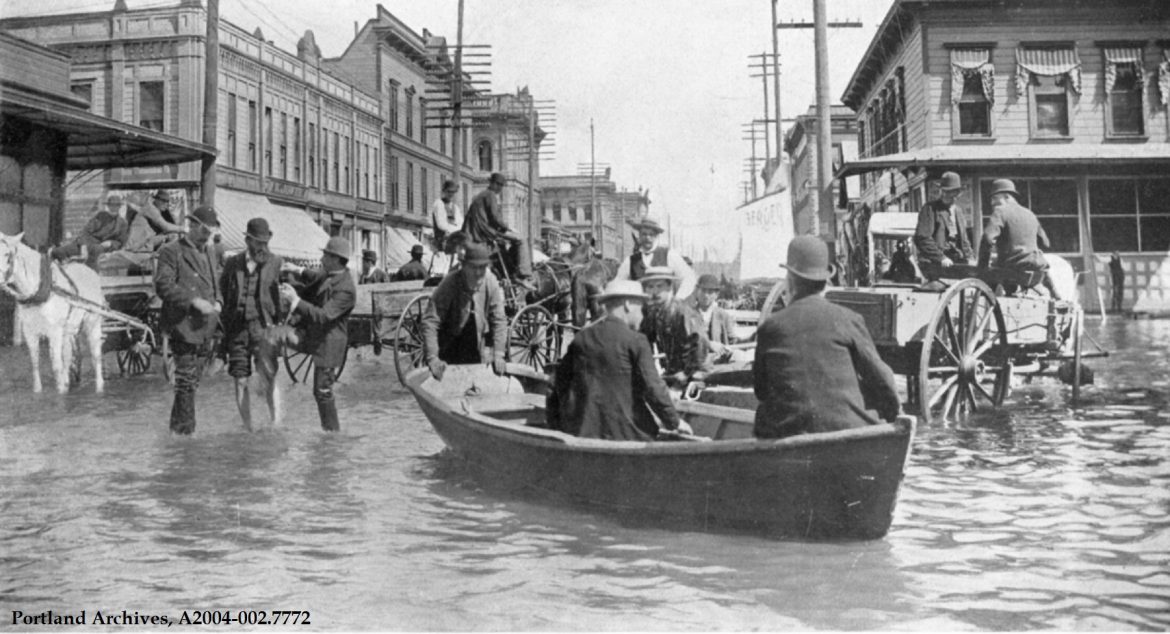

Pictures show a population determined to conduct business as usual and taking everything in stride, while often finding humor in their situation—one snapshot shows a crowd of hunters, clad in bowler hats and suit jackets, aiming their rifles at floating duck decoys.

Shopkeepers piled bricks to anchor the raised plank sidewalks in front of their establishments and constructed makeshift bridges to carry customers from one store to the next. Many didn’t bother walking—most paddled up the street and moored boats outside, where in some places goods could be passed through second-story windows.

Erickson’s Saloon, then known for its 684-foot-long bar—the longest in the world—moved operations to a houseboat anchored in the middle of Burnside Street so patrons could dry their clothes and continue to wet their whistles.

Hundreds of watercraft replaced horse-drawn carriages as the main mode of transportation, evoking iconic European cities like Amsterdam and Venice. In true glass-half-full fashion, some male laborers held boat races in Chinatown, where gambling and lawlessness were already the norm.

Before the water became stagnant, one crafty angler purportedly hauled in a 15-pound steelhead while fishing in the Union Station train depot.

The Aftermath

As much as the citizens chose to look on the bright side of things, the Flood of 1894 caused a great deal of destruction across 250 square blocks of the Rose City, with more elsewhere in the valley. More than 100 miles of train tracks were washed out, halting rail service to the city. With nowhere else to empty chamber pots, sewage began to float on the surface of the water, mixing in with rotting fish. Two drawbridges were stuck open, making travel between the east and west parts of town all but impossible.

It took nearly three weeks for the river to drop to its normal level, but the hardship continued long after that. Bacteria-laden water had to be pumped out of basements and cellars, leaving behind extremely unhealthy conditions. Erosion and seeping moisture served to destabilize the foundations of many mills, warehouses and hotels. Without the extensive photographs taken during the era, records of the downtown business district’s buildings might have been lost forever.

For scale, people can look at a placard 5 feet high on the façade of 133 Northwest Second Avenue, which shows the depth the water once reached in the area.

Seasonal flooding was a fact of life for Portland residents until the sea wall was constructed in the 1920s. Though floods of such magnitude are less likely these days, it takes but a few storm drains clogged with pine needles to fill some streets.

If that’s not enough to remind you of the city’s waterlogged past, each June Oregon History’s Doug Kenck-Crispin hosts his annual “Great Flood Field Trip” tour, which takes guests to the sites where archival photographs were originally taken. Using prints to demonstrate how much has changed over 120-plus years, the walk is a great chance to learn and enjoy a (most likely) dry summer day.

The image of the train running in front of the General Grocery building is from the Vanport Flood of 1948.