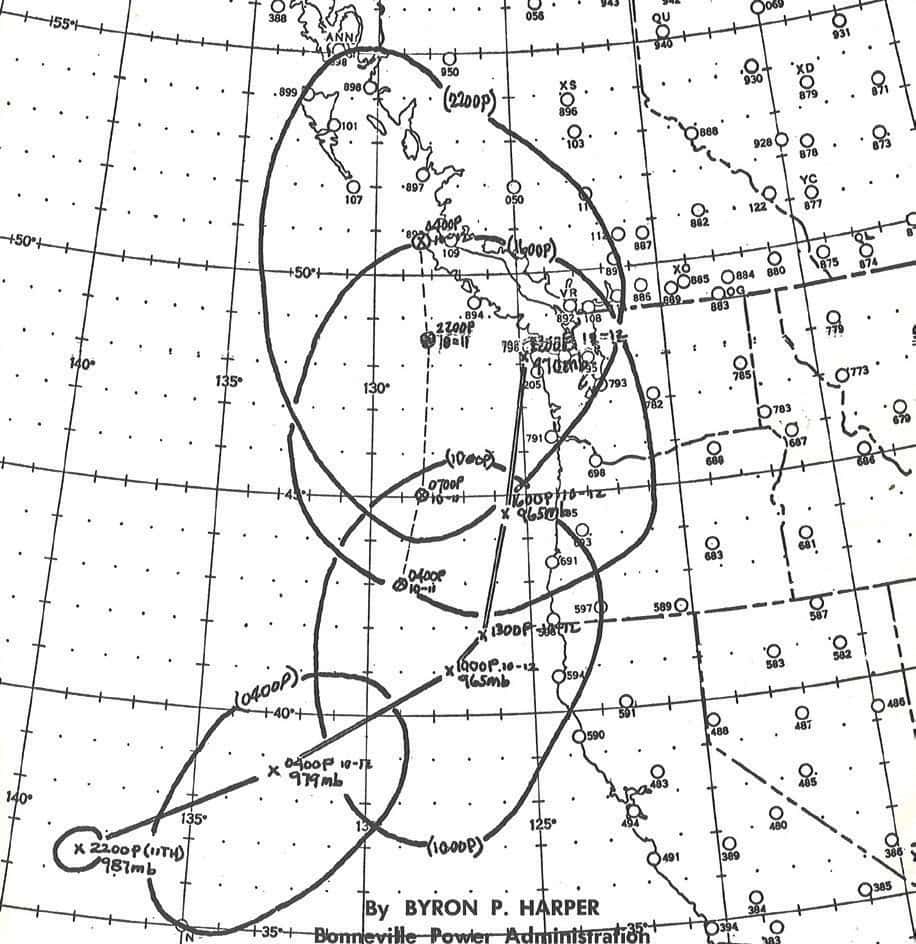

THE GREAT COLUMBUS DAY STORM OF 1962

written by Sig Unander

Jack Capell was puzzled.

As the veteran television meteorologist sat at his desk in the U.S. Weather Bureau office in Portland amid clacking teletypes and office chatter, he looked over routine weather reports that had come in that October morning. Reviewing the sketchy data, he thought he saw—or sensed—something unusual.

Capell was no novice. Ten years into a long career as a meteorologist in the Pacific Northwest, his calm, professional on-air presence was familiar to viewers. He had previously served in World War II as a U.S. Army infantry soldier, surviving almost a year of combat before helping to liberate prisoners from a Nazi death camp at Dachau.

In 1962 there was no Doppler radar, satellite imagery or computer-generated models. Meteorologists relied on spotty ship reports, data from far-flung weather stations and their own experience with volatile northwest weather patterns. Television weathermen drew crude isobars and arrows on white boards as they explained forecasts to viewers.

An early fall storm had slammed southwest Oregon the previous day, causing some damage in the Coast Range but had blown itself out. The Friday, Oct. 12, forecast was for clouds and a few showers. Good weather was expected on the weekend. Portlanders were looking forward to attending the Oregon State-University of Washington football game at Multnomah Stadium (Providence Park) on Saturday or driving up to Seattle before the World’s Fair closed for good.

Far out in the central Pacific Ocean where great windstorms form and fade, Typhoon Freda was slowly dying. The Category Three storm had gradually weakened to a large low-pressure area of unusually cold air that was now moving south from the Gulf of Alaska.

Five hundred miles off San Francisco, the fast-moving cold front collided with a warm semitropical airmass. Barometric pressures plummeted as violent eddies and currents swirled within the layered mass. Like an atmospheric Frankenstein, the moribund front, infused with warm, moist air, coalesced and began to rotate in a vast counterclockwise vortex.

At 10 a.m. that Friday, a ship west of northern California had reported a storm moving northeast. A Brazilian freighter clocked a wind gust at 100 mph. A U-2 spy plane at 55,000 feet reported severe turbulence. Yet in the Willamette Valley the air remained clear and calm.

In Portland, Capell studied conflicting data as he prepared to tape his regular 5:15 report for KGW radio, a powerful AM station that reached most of northwest Oregon. This new storm, like most, would probably track north, remain well offshore and dissipate. Bureau meteorologists issued an advisory warning but little more. Then he noticed something odd. One-by-one, coastal weather stations had ceased their hourly teletype reports.

Propelled by its own surging momentum and pulled by an extreme low-pressure gradient, the monster storm had suddenly curved inland and was now funneling north through the Willamette Valley between the Cascade and Coast ranges with incredible velocity.

An Air Force radar station on Mt. Hebo was hit by winds estimated at 175 mph and destroyed. Weather station personnel at Corvallis Airport logged a 127-mph gust, then abandoned the tower. In Eugene five died as the storm roared through the city, including a University of Oregon student whose heart was pierced by flying debris.

At Oregon College of Education (Western Oregon University) in Monmouth, Wes Luchau aimed a camera at the teetering bell tower atop historic Campbell Hall. An Air Force serviceman grabbed Luchau, steadying him in the gale as the student photographer snapped an iconic photo of the falling tower.

In Portland a gentle breeze stirred the crisp autumn air. Sunlight filtered through broken clouds, bathing the city in what some recalled as an eerie yellow glow. Capell had to make a decision: go with his gut and warn that a killer storm was about to hit Oregon’s largest city or repeat the earlier weather advisory. At 5:08, he stepped into a small booth, flipped on the mic and made the broadcast of his life.

Capell then headed across town to join anchor Richard Ross for the evening news on KGW television. He turned on the car radio and heard himself say, “The worst storm I have ever seen is approaching Portland …”

Outside the air was still, the trees unmoving. “Omigod, did I really say that?” he thought.

Convinced he had just committed career suicide, Capell turned the car south onto Vancouver Avenue. Suddenly all hell broke loose.

A massive wall of black swirling clouds loomed in the gathering dusk. Ahead of it, powerful wind blasts sheared off street signs, blew away billboards and levitated roofs. Traffic lights danced crazily on their wires. The air filled with leaves, branches and deadly shrapnel. Pieces of roofing, glass shards and boards became unguided missiles. At Portland Stockyards, the roof came off. A piece of it struck a visiting businessman in the head, killing him instantly.

In the West Hills, picturesque lanes wound along timbered ridges where some of Portland’s wealthiest residents enjoyed spectacular views. As darkness enveloped the city, winds surged to thunderous crescendos. Living room picture windows rattled and flexed, threatening to implode. Chimneys toppled. Towering firs crashed down on manicured lawns, swimming pools and cars. Atop Sylvan Hill, antenna towers designed to withstand 100-mph loads swayed like drunken sailors as gusts strained their guy wires.

Below, a carpet of amber street lights bisected by a dark swath of river shimmered across the cityscape in geometric patterns. Suddenly one section of lights went dark, followed by another and another, in an eerie chain reaction. Finally only part of the downtown core remained, an island of light in a sea of pitch black.

Photo by Wes Luchau

At Physicians and Surgeons Hospital in northwest Portland, an emergency operation was underway when the room was suddenly plunged into darkness. A backup generator failed. Nurses broke out flashlights, candles and a railroad lantern, and doctors continued the procedure.

Longshoreman Francis Murnane left his job on the river docks early to drive home. “An incredible experience,” he recalled, “… (driving) through darkened streets and falling trees. Power lines littered the streets, illuminating the darkness with sporadic flashes of sputtering fire.”

Capell drove madly through the chaos. Waved past a police roadblock he crossed Burnside, drove onto a sidewalk and raced into the television studio, ready for the upcoming newscast. “Relax, Jack,” an engineer drawled. “We’re off the air.” The new 640-foot steel television tower had crumpled to the ground.

Somehow, the radio station’s transmitter and tower remained intact. The only station still on the air, KGW became a critical lifeline for listeners and an information source for public officials including Governor Mark Hatfield, monitoring it from an emergency command post at the Capitol Building in Salem.

Station managers and television personnel crowded into the cramped radio control room where afternoon drive announcer Wes Lynch was reading phoned-in reports on air by candlelight.

Capell took the mic, reading off barometric pressures and mounting wind speeds like a play-by-play announcer. For a moment, excitement overcame his measured calm. As a 93-mph gust tore weather instruments off the studio roof, he blurted, “And there goes the weather gauge, there goes the weather gauge!”

A half mile east, a gauge on the Morrison Bridge read 116 mph. Upriver a massive World War II LST amphibious landing ship being scrapped at Zidell dismantling yard broke loose from its mooring. The darkened hulk drifted silently down the Willamette until it slammed into the Hawthorne Bridge.

In Portland’s blacked-out commercial district, police car sirens wailed as the storm blasted between high-rise office buildings and department stores, shattering windows and scattering merchandise. Officers responding to frantic reports of dead bodies found fashion mannequins tumbling in the wind.

At Portland’s eastside Lloyd Center—built two years earlier and billed as the world’s largest shopping center—35-year-old salesman Harold E. Morrison searched for his car in the darkened multilevel parking area. Unable to see a safety railing, he fell over it, plummeting seventeen feet to his death on the pavement below.

Everywhere the storm seemed to be systematically wrecking infrastructure. Thousands of trees throughout the city toppled, taking down electric and telephone lines. Upturned roots ruptured water pipes. First responders cut through downed trees to reach victims trapped in crushed cars and damaged houses. Giant Bonneville Power Administration transmission towers collapsed. PGE reported that 98 percent of its customers were without electricity.

Throughout western Oregon, families gathered around battery-powered transistor radios in living rooms lit by candles or Coleman lanterns. As the night wore on, winds gradually lessened as the storm crossed the Columbia River.

At Kelso, the single-story house of Mr. and Mrs. Dolph Price was bisected by a massive oak tree. By sheer luck, each had been in an opposite side of their home and was untouched. The structure was a total loss.

At the World’s Fair in Seattle, 85-mph gusts whooshing through the steel legs of the Space Needle made unearthly musical noises. Guests on the saucer’s observation deck 520 feet above the city felt it oscillate twenty feet in each direction. An evacuation began, but gusts jammed the elevators, forcing workers with flashlights to escort guests on a slow, vertigo-inducing descent down an external staircase exposed to the raging wind.

At the KGW studio, candles burned low as the clock ticked past 1 a.m. A weary Capell keyed the mic and gave listeners the most encouraging report so far. The storm was still “quite violent” to the north, but wind speeds had dropped in Portland and it was calm in Eugene.

The storm began tracking out to sea off the coast of British Columbia, leaving a deluge of rain. After ravaging the Pacific Northwest in just twelve hours, the great storm gradually became what it had been at first: a wet, chilly low-pressure area in the lonely reaches of the north Pacific.

Saturday dawned sunny and mild. Looking skyward, it seemed as though there never was a storm. But as residents emerged from their homes, they confronted surreal scenes. More than 10,000 trees were down in Portland alone. Abandoned cars, displaced roofs, downed power lines and debris choked streets. Highways throughout western Oregon were blocked. Forests in the Coast Range were flattened, creating a dangerous fire hazard.

Forty-eight citizens were confirmed dead and hundreds more injured, many severely. Without power and with supplies running low, overloaded hospitals struggled to provide emergency care, doctors and nurses working around the clock.

Almost every home was damaged. Some residents would wait weeks for the lights to come on again. Families cooked on camp stoves in candle-lit living rooms and huddled around fireplaces as the autumn chill set in. Blown-out windows and damaged roofs were covered with plywood. New friendships blossomed as people shared food, tools and blankets with neighbors they hardly knew, often with a wry sense of humor about their predicament.

Chain saws were fired up. For many weeks their buzzing roar echoed through neighborhoods as utility crews and homeowners felled and bucked countless storm-damaged trees.

An army of electricians, telephone specialists, medics, carpenters and claims adjusters arrived from out of state to bring order to the chaos. Utility linemen made heroic efforts to restore electricity, working seventy-two hours at a stretch.

In the end, the rampaging extra-tropical cyclone was the costliest natural disaster ever to hit the region. Its sudden and extreme violence shattered the perception of readiness. It altered Oregon’s civil defense system and forest-management practices and exposed the vulnerability of the electrical grid, which had to be rebuilt to a more resilient standard.

Evidence suggests it was a very rare event. Giant fir and spruce trees in the Coast Range that had withstood centuries of fire and storm came down. The 700-year-old Clatsop Fir, weakened by the big blow, fell soon afterward. No records since European settlement began tell of a storm of such magnitude, nor do Native American oral traditions.

Six decades on, the Columbus Day Storm is still considered the standard against which all other large Pacific Northwest storms are measured. And for those who lived through that terrifying, tragic and memorable night, it remains a unique and indelible experience.

FLIGHT OF THE AEROCAR

On Oct. 12, 1962, airports throughout western Oregon became tangled junkyards as the Columbus Day Storm roared through the Willamette Valley. Pilotless planes snapped tie-downs, briefly going airborne before smashing into others.

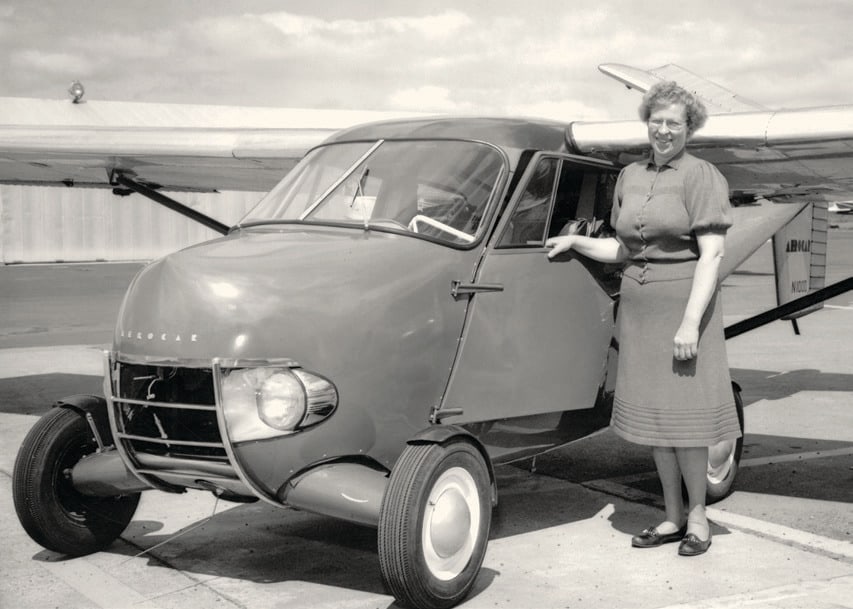

A vintage Aerocar lightplane operated by Wik’s Air Service took off from Hillsboro Airport to radio afternoon traffic reports to Portland commuters on KISN radio. As it gained altitude and approached the city, powerful gusts buffeted the aircraft, reducing its ground speed to zero. Witnesses swore they saw the Aerocar fly backward.

At the controls was Ruth Wikander, a veteran flight instructor and member of the Ninety-Nines, an international women’s aviation organization. As she fought for control, Wikander kept the colorful red-and-white aircraft pointed into the wind. Somehow, she managed to coax it back to Hillsboro, landing crosswise on the grass. Several mechanics ran out and held the plane’s wings down as she taxied it under full power into a hangar, where it rode out the storm.

The Aerocar that Wikander flew that day, N103D, was one of six built in the 1950s by eccentric aviation genius Molt Taylor for a postwar market that never materialized. The plane could be converted to a drivable car in a few minutes by one person. It had previously been flown to Cuba for an international exposition. Raul Castro took a test hop but struck a horse on the runway, damaging the plane. The dictator’s brother declined to purchase it.

The plane was flown back to the factory in Boston, repaired and leased to KISN. Wikander had the honor of driving it in the 1962 Rose Festival Parade, where it drew considerable attention. N103D is in storage in Colorado, reportedly for sale for $3.5 million. Wikander died in a tragic aviation accident in 1968.