Kelly Butte’s hidden nuclear hideout

written by Sig Unander

It was a lazy late summer day in Portland, not unlike others. It had dawned cloudy but by mid-morning warming sunshine cleared the light overcast.

At 10:35 a.m. air raid sirens split the city air with a high-pitched wail signaling an impending attack. Early warning radar had detected unknown aircraft, possibly Russian bombers, over Canada, on a course for Portland.

Deep beneath a forested volcanic butte east of the city, Mayor Terry Schrunk and other key officials hunkered down in the operations room of a two-story underground Command Center designed to preserve city government and maintain communications in the event of a nuclear blast.

Firefighters and police went into action as hospitals, schools and offices emptied. Thousands of cars filled main evacuation routes heading out of town. Shoppers crowded into building basement bomb shelters and tuned radios to emergency frequencies. Noon passed. Enemy aircraft were expected over the city at 2:45. People waited anxiously while minutes ticked off.

As the Cold War threatened to turn hot in the early 1950s, Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin kept a chokehold on eastern Europe. American fighter pilots dueled with Russian MIGs high above Korea. Both superpowers developed arsenals of atomic weapons and long-range bombers to deliver them.

Civil defense planning, first prompted by the threat of a Japanese attack on the West Coast during World War II, took on new urgency. Schoolchildren were taught to duck and cover. Backyard fallout shelters were dug, an emergency radio alert system was established and placards with the ubiquitous triangular civil defense logo posted on buildings.

Portland was at the forefront of these efforts. Strategically located at the confluence of the Columbia and Willamette rivers, the Hiroshima-sized inland seaport was designated a “critical target area” for a nuclear strike, and the city had a plan.

In 1952, voters passed a $600,000 levy that enabled major city departments to work together to provide emergency services and educate the public in disaster response. Three years later Portland held a citywide exercise called Operation Green Light, during which 1,000 city blocks and 101,074 residents were successfully evacuated within a half hour.

Impressed by this example of planning and civic cooperation, the CBS television network produced a documentary program in which Portland citizens —starring as themselves—re-enacted Operation Greenlight for the cameras.

Narrated by actor Glenn Ford, the film shows schoolchildren, office workers, police and fire personnel as they hear alerts and follow planned emergency procedures. Radio announcers cut in with updates and instructions. In one scene, Mayor Schrunk strides briskly through the underground Command Center. Sanding before a wall map, he fixes the camera with a stony gaze and gravely intones, “In less than three hours, an H-Bomb might … fall over Portland.”

As updates are given, “THIS IS NOT AN ATTACK” flashes on screen, doubtlessly intended to spare CBS the flak it had received after broadcasting Orson Welles’ panic-inducing 1938 radio drama simulating a Martian invasion of Earth. The television program’s ending was deliberately unresolved, leaving the viewers to consider what they would do in such an emergency.

The documentary was filmed in multiple locations in Portland on September 27, 1957 and aired nationally in December of that year as The Day Called X. While it depicted an imaginary attack, it showed what would have occurred had hostile aircraft actually penetrated Oregon’s airspace.

The underground Command Center in which Schrunk and other key officials acted out a scenario that fortunately never materialized, was the nerve center of Portland’s civil defense setup. The special levy and matching federal funds paid for construction of a “Disaster Relief and Civil Defense Communications and Control Center” with everything that city leaders, emergency managers and 250 staff would need to keep government functioning for two weeks after a nuclear attack and to coordinate emergency services.

A photomap included in the 1954 funding application shows bomb target areas A (downtown Portland) and B (docks and fuel storage facilities downriver) with the Control Center site located on Mt. Tabor. It was later moved to Kelly Butte, a few miles farther from the target areas.

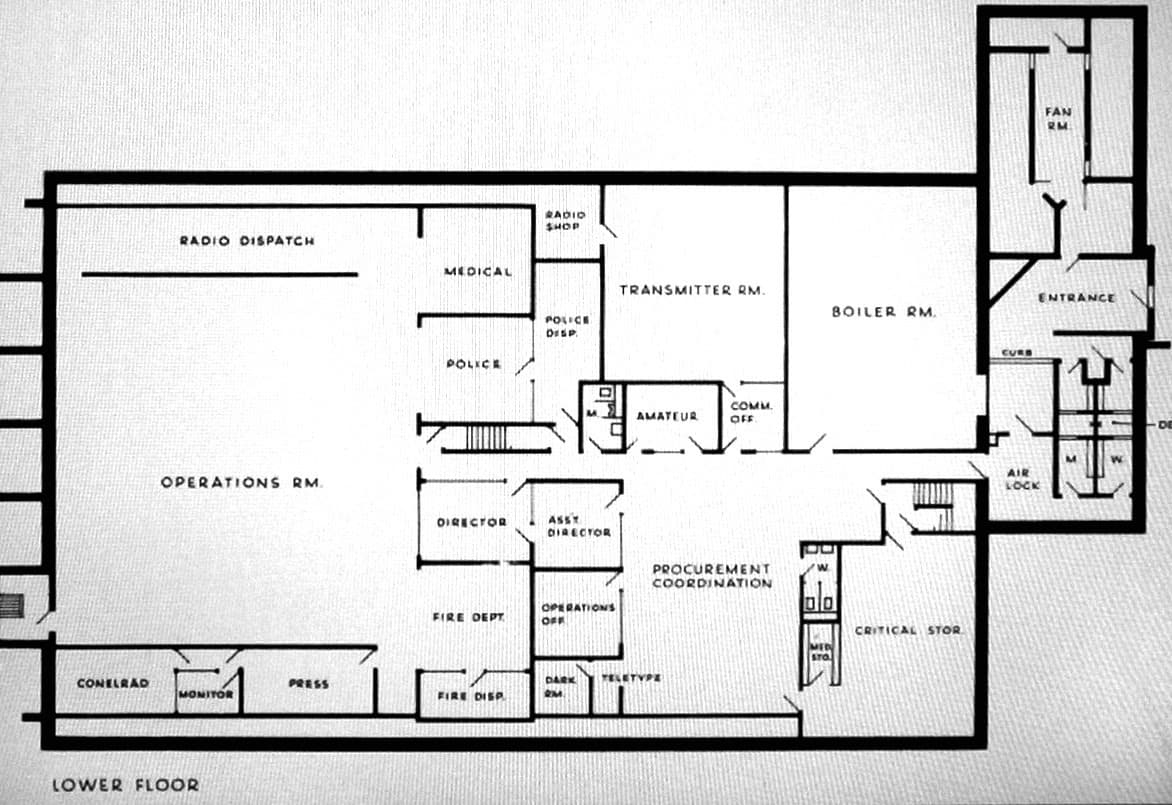

The design specification was an 18,820-square-foot two-story rectangle measuring 180 by 90 feet with an arched roof of reinforced concrete two feet thick. Reinforced steel doors and air locks sealed the entrance to prevent blast waves of a 50-kiloton airburst from penetrating. There were “provisions for air conditioning and filtering biological, chemical and radiological agents.” On the east side of the Butte facing away from the target areas, a large plot was cleared, leveled and excavated. A foundation was poured, the structure built and covered with thirty-five feet of packed earth.

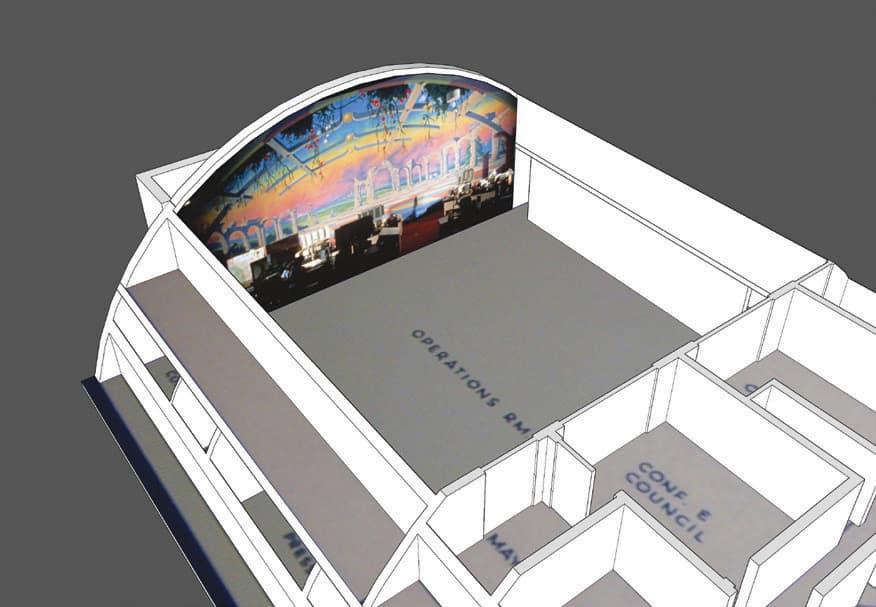

The facility’s upper floor contained offices for the mayor and commissioners, a kitchen, cafeteria, dormitory and communications center. The lower level housed emergency services managers, dispatchers, a generator, ventilation equipment, food and medical supplies. A 35-foot high operations room common to both levels contained a large wall map of Portland, a podium, desks and cubicles for civil defense and emergency services personnel. Within the bunker, more than three million city documents on microfilm were preserved. Above ground, a 230-foot communications tower was erected.

In 1956, the facility was completed and a public dedication ceremony was held. It was prominently featured the next year in the CBS documentary and was a source of civic pride.

Just six years later a different kind of emergency tested the command center’s viability. Early on October 12, 1962, remnants of Typhoon Freda merged with warm currents off the West Coast to set up a knockout blow. In one terrifying night, the Columbus Day Storm tore through Oregon, leaving 48 dead, hundreds injured and damages in the billions of (today’s) dollars. Television antenna masts in the West Hills collapsed in the hurricane-force winds but the reinforced tower atop the bunker stood intact. Inside, everything functioned perfectly: emergency personnel continued to send and receive messages and track the storm. Yet the Command Center played no major role in managing the disaster.

On that fateful and chaotic night, Mayor Schrunk was out of town. The acting mayor, a Portland city commissioner, elected to direct emergency management operations from City Hall. Governor Mark Hatfield handled statewide emergency management from his office in the Capitol building in Salem.

Soon after the storm, the Cuban Missile Crisis took both superpowers to the brink of nuclear war. Commissioner Stanley Earl led an effort to disband Portland’s civil defense program and close the Command Center, arguing that they were a waste of funds and no longer effective in light of more powerful hydrogen bombs delivered by missiles. In the summer of 1963, a ballot measure to continue funding the city’s civil defense program failed and the Council voted to end it. Ironically, the city hailed as the poster child for civil defense became the first to defund its model program.

For a time, the Command Center was used as a training facility by the Portland Police Department. By 1968, it was in suspended animation, maintained by a solitary city worker. In the early 1970s, the facility was converted into a communications center for the newly established Bureau of Emergency Communications. In 1974, BOEC moved in and began handling calls for city and county police agencies. A few years later, it began serving fire and medical responders, upgrading its equipment when the 911 call system was implemented.

As it turned out, the operations room, where call-takers toiled at their consoles before glowing computer monitors, had drawbacks. The large room made some people feel claustrophobic, and it had a stark institutional ambiance. Some workers got sick—it was said—from something in the air. There were indications of hazardous dust and seasonal affective disorder, according to Portland historian Jeff Felker.

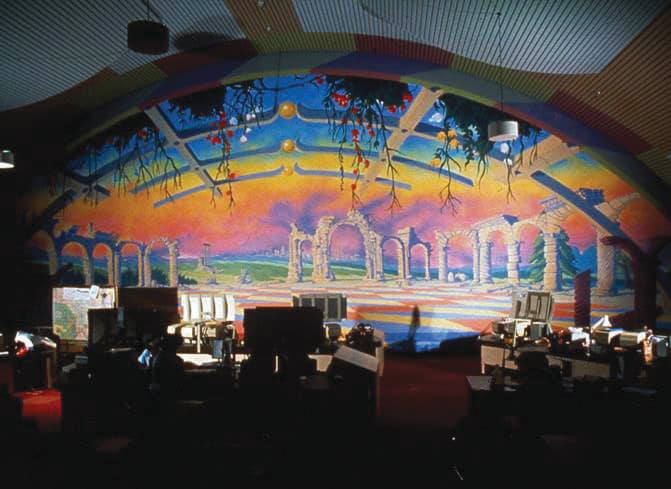

In an effort to cheer up the place and add a feeling of depth and space, noted Portland artist Henk Pander was commissioned to paint a large mural on the operations room wall that operators could see as they worked—a sweeping, surrealistic panorama of the ruins of an ancient Syrian city.

In 1992, BOAC moved operations to a new state-of-the-art above ground call center. Decommissioning the old facility was hasty. Almost everything—equipment, cubicles, furniture, cabinets, lighting, control panels and even records—was simply abandoned. The last person out was a Portland firefighter who searched to ensure no one would be trapped inside.

After the bunker was sealed, the communications tower was removed. The site became an object of curiosity and the target of vandals. The concrete entrance, overgrown with vegetation, was defaced with colorful graffiti. City crews hadn’t adequately blocked the emergency escape exit and vents. Thrill seekers and amateur archaeologists worked their way down into the stygian blackness to explore and take photos. Others had different intentions. “Makeshift camps were set up inside the belly of the bunker. The transient force took copper wire, aluminum, food, clothing and historical items,” according to Felker. Within the spooky subterranean realm, its denizens breathed toxic air, consumed drugs, defecated and set fires. Someone splashed black paint on Henk Pander’s mural. To stem the illegal activity, more dirt was bulldozed over the site, covering the exit and vents.

The Lost Palmyra Mural

After the Kelly Butte Civil Defense Command Center became an emergency call center, artist Henk Pander was commissioned to paint a decorative mural on its main wall. The intent was to provide stressed-out 911 operators a sense of space, timelessness and natural beauty.

The composition depicted the ghostly ruins of the Syrian city of Palmyra against a vast, spectral sky. “I wanted it to represent ancient history of a thousand years ago, reminiscent of the Roman Empire,” he recalled.

A smaller painting was completed and scaled up. Pander and an assistant, working on scaffolds, gridded off the 30 by 90-foot wall and laboriously painted in the squares. Entrance doors were opened so operators working on the other side of hanging plastic sheets wouldn’t be overcome by paint fumes.

The result was the largest indoor mural ever painted in Oregon. “I extended the architecture into space with vanishing points. The elements I painted into the wall are all related to the point where you enter the space, so the illusion was perfect,” Pander noted. “I painted a sky that goes through the spectrum: yellow, orange, green, blue.”

The lighting element was also important. A friend set up a computerized projection system so that light falling on the painting “moved slowly through the spectrum in a twenty-four hour (time) cycle” giving workers a sense of day and night within the underground shelter.

Since Portland was settled Kelly Butte has seen many uses, few with permanence. A county jail was erected in 1906, and in an adjoining quarry, shotgun-toting deputies watched convicts break rocks into gravel for Portland’s expanding street network. An Isolation Hospital on the western slope housed patients with serious communicable diseases. There was a police firing range, a water storage tank and a city park.

The war of words between former president Donald Trump and Korean dictator Kim Jong-un and Vladimir Putin’s recent bombast have renewed the specter of nuclear war and raised public interest in civil defense. Bomb shelters are back, more stylish now than the concrete block cubes of the ’50s. Radiation-blocking potassium iodide pills and emergency supplies sell briskly. Given the renewed threat level, could there again be a need for a hardened facility where key officials could ride out an attack, assuring continuity of government?

The one-time emergency command center is still there. Environmental and technological upgrades would be required to reactivate it. BOEC spokesman Dan Douthit gets occasional media inquiries but said there are currently no plans to resurrect it. “My suspicion is that, because there was something in the air there that was a challenge for people to work in, that would have to be mitigated. The question would be: Is it cheaper to open it back up and clean it out versus starting somewhere else?”

The Center site lies near the butte’s 593-foot summit. The access road is blocked by a steel gate. Beyond, the road ascends steeply and the pavement gives way to a patchy field of mud and grass curiously devoid of overgrowth. The roar of traffic below is muted by surrounding stands of Douglas fir and maple, only an occasional bird call breaks the silence. Routine maintenance is absent; no park signs or historic markers provide information or welcome visitors. The atmosphere is one of benign neglect, some say creepy. No homeless camps are visible, but discarded clothing and trash on unmarked trails leading deeper into the forest suggest they are there.

At the clearing’s edge where the terrain rises toward the summit lies the only part of the bunker remaining above ground. A low concrete wall protrudes from a rounded earthen berm, an emergency exit now sealed by a graffiti-covered block. Gravel fills an opening below where tunnelers have been at work.

Fifty feet or so beneath the surface lies a dark, cavernous chamber, a Cold War time capsule containing relics both functional and artistic. “It would be a great museum,” Felker said. “That’s what I always envisioned it to be—a Cold War civil defense museum.”

Even if the one-time command center is never reactivated for civil defense it might still have a useful afterlife as a restored facility educating future generations about a pivotal time in history when the city and nation faced an unthinkable threat.