Avex ‘Stoney’ Miller was 4 years old when his father, Avex Sr., a Wasco Indian, put him on a gentle “bulletproof ” horse to learn how to track cattle across the Warm Springs Reservation.

“We’d be up there in the hills riding for cattle, and dad would point out a cow track and tell me to stay on it,” said Miller, now 64. His dad would ride off and come back to check on his young tracker, “If I had lost the track or got it mixed up with another cow, he’d give me a little light swat on my leg and put me on another track.”

In the vast high desert topography of swales of obsidian rock, loamy sand and sagebrush, tracks could easily disappear or begin to look like one another. It took the young apprentice a couple years before he could single out the distinctive marks in a cattle’s track and follow it through “hell or high water.”

For generations, Miller’s forefathers made their living knowing how to track and hunt wild animals. Necessity made them good. That talent was passed down from one generation to the next.

Avex Sr. was a Wasco Indian living on the Warm Springs Reservation. His wife was white, a nurse who came to the reservation in 1937, when a hospital was built at Warm Springs. As spouses in the first mixed marriage between an Indian and a Caucasian on the Warm Springs Reservation, Miller’s parents were often the subject of taunts. Likewise, young Stoney Miller took his knocks, too. “I fought the white boys because I was Indian,” he recalled. “I fought the Indian boys because I was white. Mostly I stayed to myself.”

It wasn’t until Miller was 6 or 7 that he began to apply himself to tracking humans.

Miller and his dad were riding for cattle when they came across a recently abandoned pickup truck along the road. “Dad motioned me over and asked what I could tell from looking at the tracks. I didn’t know. He said they were hunters who had seen some deer up the hill, and that the deer took off before the men had time to shoot.”

After that day, Miller and his father increasingly began following human footprints whenever they were out hunting together—passing the tracking skill from one generation to the next. “Dad would explain what the person was doing and told me how he was seeing it from reading sign,” said Miller. “I was a pretty fast learner.”

He tracked alongside his father for years, learning to divine things that most people couldn’t see. His father told him that when he could track a grey squirrel from one tree to the next, only then he would be a competent tracker. One day Stoney and another boy were in the woods and Stoney spotted a squirrel in a tree. He turned away and told his friend to watch and tell him when the squirrel had moved on to another tree. Later that day, his friend revealed to Stoney’s father that young Stoney had done it—he had tracked a squirrel from one tree to another. His father’s teaching was complete.

Soon Miller could read signs as though they were words in a book. “A tracker can tell if a person has had a leg or back injury by the way they put their foot on the ground,” said Miller. “Maybe you step on the outside, or inside, maybe you favor your heel and so you put pressure on the ball of your foot. The way we place our feet, and our stride, shows that pain.” He could accurately guess a person’s weight in the depth of their footprint. He could fairly determine the gender from a track. Typically a woman’s stride is more in a straight line, a man’s gait more spraddled. A city boy walks with his toes turned slightly outward from walking on pavement and stable surfaces. A country boy has a more pigeon-toed gait from walking on dirt and over rocks. Members of the military are taught to elongate their stride.

The first time Miller put his newly honed tracking skills to real use was when he was 13. A young boy had become separated from his family while on an outing to dig wild potatoes above the Miller’s farm. Miller’s father told his son to saddle a horse and go help look for the boy. It took him close to an hour to work his way to the top of the ridge, where he found several men on horseback already looking for the boy. Young Miller joined them and soon began finding signs of where the boy had been. The signs told him that the boy hadn’t been worried and had been playing around, and climbing trees. After about thirty minutes, one of the trackers called the others over. “We rode over, and this fellow is sitting on his horse, arm resting casually on the saddle horn,” Miller recalled. “I saw this little shoe sticking out from under a juniper root wad. I got off my horse, not knowing if the boy was alive or dead.” Miller pulled the sleeping boy out from his makeshift bed. “I didn’t know if he was going to hug us or start bawling,” he said. “When we brought him back to his family alive, they were so full of joy and happiness. I’ll never forget that moment.”

Stoney Miller rode back home after returning the boy to his parents. “Dad was busy seeding a field, and he saw me coming off the hillside, stopped the tractor, got off and walked to the gate,” Miller recalled. “He waited for me and asked if we found the boy. He told me ‘good job,’ and that made me feel like I had really done something worthwhile.”

That day, said Miller, he learned something about tracking—a lost child will generally climb a hill because they have something familiar to grab onto while doing it, whether it be rocks, twigs or sticks. Adults, however, usually go downhill, preferring a path of least resistance. Sometimes they sit in one spot for a spell, until they figure out a direction to head. Lefthanded people generally wander to their left. Right-handed people head to their right. These notions are especially true for people on horseback. Over time, a right-handed rider will put more pressure on the left reign and guide the horse right and conversely for a left-handed rider.

The Science of Tracking

The science of tracking ultimately lies in the ability to first spot the sign. The art of tracking is interpreting that sign. Signs are rarely perfectly preserved footprints in moist soil. They can be a bent twig or disturbance of lichen.

The tracker uses a pole to measure the size of the footprint and the length of a stride. The stick is laid on the ground from the last known sign and the hunt begins for evidence of the next step. It is often painstaking and excruciatingly slow for a tracker to follow a subject through the woods or over a rock-strewn outcropping because, in these environments, the perfect set of prints is rare.

Of course, the modern innovations of GPS, heat-seeking infrared devices have been immensely helpful in tracking today. Yet from Miller’s perspective, the invention of the flashlight was the most advantageous tool brought to the trade in the past decades. The worst time of the day to track is high noon when the sun is directly overhead and everything appears one dimensional. Tracking with a flashlight, however, is ideal.

The reason for this becomes evident quickly. Shadows are everything to a tracker. With shadows you see the indentation made by a boot, a scuff mark on a rock, dust on a leaf, a few grains of sand where they shouldn’t be. By laying a flashlight on a track, and pointing it in the direction the tracks are headed, the next sign or track is revealed. Even when the trail passes over a bed of pine needles, tracking is easier because pine needles have a shiny side from where they have been exposed and a dull side underneath. When pine needles are stepped on they generally roll. “The dull marks in the sheen of a bed of pine needles can be followed almost at a run,” said Miller.

Miller went on to have a long career in law enforcement as a deputy sheriff in Malheur County, with the Madras police force and as acting chief of the Warm Springs Tribal Police.

Early in his law enforcement career, while Miller was working as a deputy for the Malheur County Sheriff’s Office, he was called in to track two suspects and try to locate the body of a police drug informant. One of the suspects had admitted they murdered the informant. The crime took place during a rain storm and that proved beneficial to Miller. Even though several months had passed, he was able to cut sign in this sparsely populated area of Owyhee County and piece together a trail of footprints, blood-splatter, displaced rocks and strands of hair. He followed that chain of evidence and recovered the body of the police informant. The suspects stood trial, were convicted and remain incarcerated.

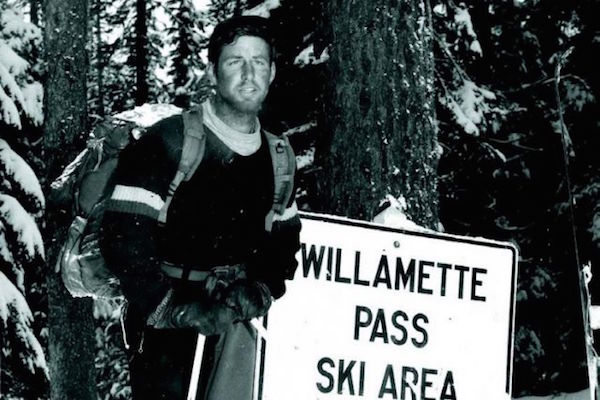

A later case, however, remains unsettled for Miller. It was the search for Corey Fay, a 17-year-old junior at Jesuit High School in Beaverton. The teenager was on an elk hunting trip on November 23, 1991 in the Cascade Mountains when he disappeared. Two days later, Miller and others were called in to track him.

“Whenever I’m called in, I try to get as much background on the missing person as I can,” said Miller, who was then with the Warm Springs Tribal Police. “As a tracker, you need to be able to get in a subject’s mind and think like they think.” Miller interviewed Fay’s sister, who acknowledged that he was a city kid but one who loved the outdoors and read lots of books about hunting and fishing. About the third time Miller talked to her, she mentioned that her brother had an unnatural fear of the dark.

Later, when Miller was following Fay’s tracks, he found a place where Fay must have been walking in the dark. “He was stubbing his toes on roots and stumps, and several times he panicked, ran and fell down,” he said. The trackers were finding signs, but after ten days or so, the search was called off. Fay’s body was never found, although after the snow had melted, his clothes were found, all laid out in a straight line—a sign of the madness behind hypothermia. His pack was hanging in a tree, his rifle leaning against another tree. Searchers also discovered tooth and bone fragments. “Every once in a while, I think back over that case, wonder what I might have missed and what really did happen to that kid,” said Miller.

Perhaps because of media stereotypes, Native Americans have been repeatedly cast as the best trackers in the world. Miller disagrees with that notion, but grins, shrugs his broad shoulders and qualifies his answer. “A lot of Indians are raised close to nature,” he countered, “out in the country, chasing cattle and riding horses.”

Now retired and bothered by asthma and a “gimpy leg,” Miller teaches tracking for law enforcement agencies more than he tracks. He emphasizes four key virtues he learned along the way: patience, perseverance, keeping an open mind and empathy for the lost person. “They need to understand it all—fear, panic, the breakdown in mental function—of someone who is lost and disoriented,” he said. “If someone can do all those things, then there is no reason they can’t become a top-notch tracker. You don’t have to be Indian.”

A Tracker’s Perspective

• A lost child will generally climb a hill.

• Adults usually go downhill.

• Left-handed people generally wander to their left.

• Right-handed people head to their right.

• A tracker can tell if a person has had a leg or back injury from their footprint.

• A tracker can accurately guess a person’s weight by the depth of their footprint.

• A woman’s stride is straighter.

• A man stride is more spraddled.

• A country boy has a more pigeon-toed gait from walking on dirt and over rocks.

• Members of the military have longer strides.

All photos by Christian Heeb

This is a wonderful article but it truly just scratched the surface of a great man who I am proud to call my good friend. Not mentioned in the article is how Avex has trained literally hundreds of community members how to track or cut sign. A no-nonsense man, he has taken the time to teach young men and women this skill but beyond that, how to be better members of our community. I can not say enough about this man other than how very proud I am to have him and his family as my good friends.

Great article. Thank you. As a Tracker myself and a volunteer with Oregon Search and Rescue, I enjoyed the stories about the training Avex Miller was given by his Dad. Especially being swatted for not following the correct track. The Indonesian tracker trainers do the same thing I hear, but use a bamboo cane to keep their students focused. Thanks again for the interesting read.