The history of Oregon’s ghost towns lives on

written by Ben McBee

Oregon has more ghost towns than any other state, largely a result of early booming mining and lumber industries that have since faded from prominence in the modern world. While some communities disappeared as the money dried up, others were victim to the destructive power of nature. These places may have vanished, but they left behind eccentric histories that made their mark on Oregon’s quirky past.

Bayocean

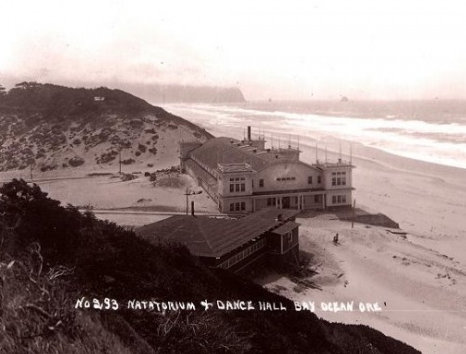

During a hunting trip along the Oregon Coast in 1906, real estate developer Thomas Irving Potter downed a goose on the seaward side of Tillamook Bay. With visions of its scenic potential, he returned to Portland and purchased the spit of land in partnership with his father Thomas Benton Potter. On that 600-acre plot they dreamed of creating “The Atlantic City of the West” and at first, their success was plentiful, despite an initial lack of infrastructure.

Potter transported tourists aboard his own private vessel, the voyages sometimes lasting as long as three days. Thanks to a particularly choppy inlet, many showed up seasick and frightened.

Still, what they experienced next cured their trepidations. By the mid-1920’s, Bayocean, the community quite literally named for its gorgeous views to the east and the west, was a thriving vacation destination, complete with a luxurious central resort, a bowling alley, a 1,000 seat cinema and a heated natatorium with a built in wave machine.

To improve nautical travel, the Army Corps of Engineers suggested building two jetties at the mouth of the bay, a 2.2 million dollar undertaking. But to cut costs, Bayocean residents only funded one, creating an imbalance that subjected the shoreline to increased erosion.

Ultimately, the misstep would be their ruin. Slowly, one by one, the buildings tumbled into the Pacific and the people left. No structures remain standing today but visitors can walk the site at Bayocean Peninsula Park and imagine the town that fell into the sea.

Cornucopia

In 1884, a man named Lon Simmons chanced upon one of the largest gold deposits in the Pacific Northwest, nestled in the southern edge of Wallowa-Whitman National Forest. As more and more claims were staked, a town sprung up in the foothills, Cornucopia, and wealth flowed from this horn of plenty.

Up to 700 men worked in the mines on 12-hour shifts, seven days a week. Initially, road bumps plagued the operations. In 1902, the mining companies were foreclosed after failing to pay a collective $40,122 engineering bill. Severe isolation and antiquated equipment hindered the profitability of the operations, but by the 1920’s electricity and technology finally developed and the outpost flourished. They even built a stamp mill with 20 enormous hammers that could crush 60 tons of ore each day.

Fiddle playing and Saturday night dances were the highlights of the week in that far away place.

In 1942, President Franklin Roosevelt shut down all gold mining so prospectors could dig up metals for war, and Cornucopia faded away. Several summer homes and a recreational tourism lodge now occupy the otherwise deserted area.

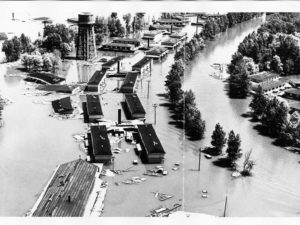

Vanport

At the onset of World War II, a hurriedly assembled public housing project designed for wartime shipyard workers sprung up on the edge of the Columbia River. Dubbed Vanport, a portmanteau of nearby Portland and Vancouver, it was home to 40,000 people at its peak, making it Oregon’s second largest city at the time.

Following the war, its population was cut in half, but the Housing Authority of Portland established Vanport College to appeal to returning veterans and their families. It enrolled 1,924 students in its first year and succeeded in retaining the community.

However, everything changed one tragic Memorial Day, May 30, 1948, when an upriver dike failed, flooding the city and killing 15 people.

Nearly half of the citizens were African American and de facto segregation was a devastating reality. The authorities’ inadequate warning and apathetic response to the disaster have been attributed to racist sentiments in the government. Whether these claims are justified or not, the outcome remains the same – the city was wiped off the map.

Vanport College, “The College That Wouldn’t Die”, refused to close and transferred to a downtown campus, eventually becoming Portland State University.

Today, Portland International Raceway marks the land on West Delta Park where Vanport once stood.

GRAVITY FALLS IS REAL!!!!!!!!

The town of Wendling Oregon 18 miles northeast of Eugene, was at one time nearly as large as the city of Springfield.It was a company town so nearly everything was transportable via rail car. When the mill burned down for the third time, in the mid 40s the town was disbanded, and most everything loaded up and shipped away. My family has owned 2 of the last remaining buildings from the town for 70 years since it died a home built around 1910 and a garage/laundry house built in the 20s when cars and hygiene came around. the only murder ever recorded in town history occurred on the northeast corner of our land over…chicken shit a rooming house owner was closed for cleanliness issues due to a pile of chicken dung a farmer was chucking over the fence hotel owner picked a fight chicken rancher wounded hotel owner killed a constable and himself before the night was over I feel so very grateful to be part of such a rich unique local history!

Wow. I really wish we could establish a photo history of Oregon through the years.

can i metal detect around that house your family owns ???? [email protected]

About Vanport. After the war ended, the population of Vanport was estimated to be between 18,000 to 18,500 of that, approximately 6,000 were black. After the war, Vanport was home to college students, instructors, veterans, returning Japanese from internment camps, and low-income individuals. Stephen Epler, the head of Vanport Extensions center (the precursor to Portland State University) lived in Vanport with his family and was there on the day of the flood.

The Vanport flood was a massive flood which affected the entire Columbia River Basin (from Vancouver British Columbia, to Washington, to Idaho, Montana, and Oregon. It was a railroad berm that gave way causing water to surge into Vanport with devastating impact — not” an upriver dike that failed.”

The number of people who died, according to official records, is 15-18. Sheriff Pratt, a Multnomah County sheriff, estimated the death count to be 51 when he was interviewed by a reporter.