written by Sheila G. Miller | photos by Tim LaBarge

Do you have malaria? A drop of blood and one minute is all Hemex Health needs to tell you the answer. With more than three billion people in 95 countries at risk of contracting malaria, that minute could make all the difference.

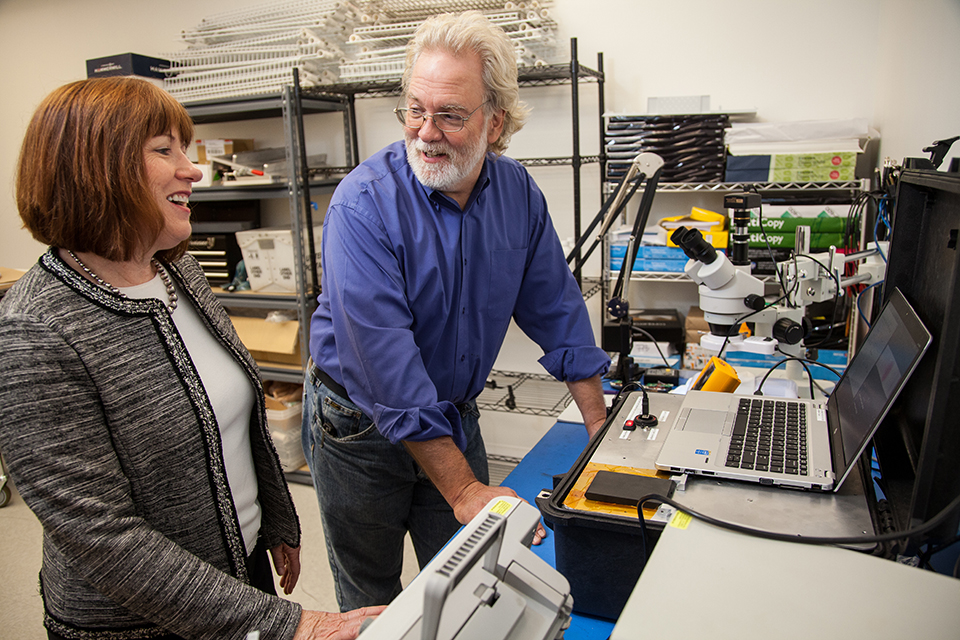

“That’s what we need in the developing world,” said Hemex co-founder and CEO Patti White. “We need to get that result right away, because you might not find (the patient) again if you need to tell them results.”

Straight out of graduate school at University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School of Business, White went to Hewlett Packard, where she worked to develop the early personal computers.

“Those were the fun years, when personal computers were really changing the world,” she said. “Then it wasn’t that way by the ’90s, so I was really looking for something that gave you that big feeling, that you were really changing people’s lives with technology.”

In 1995, White moved to Oregon to work in HP’s cardiology division. There she met Peter Galen, with whom she joined forces in 1997 to start Inovise Medical, which developed heart sound technology. They later worked together at a vision diagnostics company.

In 2015, the pair decided it was time for another startup. “We must be crazy or something,” White said. “But a number of products we’ve done … over the years have had an impact in the underserved parts of the world. It is really exciting to go to a place like China or India and see the products you’ve developed being used.”

With that inspiration, Hemex was born. White and Galen looked for technology that had already been invented but not developed for use. “We were not trying to start with an invention. We wanted to be more focused on development.”

The pair visited more than 20 universities and research centers looking at technology portfolios, eventually identifying two technologies developed at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland that they knew could have an impact. They began to devise a quick, accurate diagnostic device that is easy to use in the field.

“We also felt that it solved really big, unmet needs,” she said. “These products really do solve a real problem that nothing else does today. … And we thought we could raise money to fund the development.”

As it stands, malaria is currently diagnosed in one of two ways: microscopy (putting a drop of blood on a slide and having a trained expert examine the blood) or rapid diagnostic tests (which look and work much like pregnancy tests, but with blood instead of urine). Microscopy requires electricity and can take thirty to sixty minutes per person. It also depends on a diagnostician to correctly read the blood. RDTs take twenty minutes. Both tests generally miss malaria when it’s in the body in low levels.

By contrast, Hemex’s device takes one minute per blood sample. It can find the disease lingering in the blood at low levels, and the device can fit in the palms of your hands. “In an area where you’re trying to eliminate malaria, you might have to test a whole village of people,” White said. “A one-minute, accurate test is a huge advantage.”

The device can also test for sickle cell disease, an inherited red blood cell disorder. Eighty percent of those who carry the trait live in the developing world. In the United States, every newborn is tested for the disease. In developing countries, there’s no affordable or accessible test for the disease. Half of those who have the disease die by age 5. Studies show that early diagnosis and low-cost treatments like penicillin and a pneumonia vaccine can prevent 70 percent of those deaths.

Hemex’s device can test for sickle cell disease and the trait in eight minutes. The device is the same, and a user puts in cartridges the size of USB sticks to test for different disorders. Eventually White would like to expand the number of diseases the device can diagnose, but, for now, Hemex is starting with malaria and sickle cell disease.

In October, the Bend Venture Conference awarded $50,000 to the company in its social impact competition. The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office honored the university’s malarial detection technology with one of its four Patents for Humanity Award.

The product prototype has been tested. Now Hemex is raising money, developing more prototypes and working on a final design. White said the company is about one-and-a-half to two years away from mass-producing the device.

“A lot of times, people think that to do good for the world you can’t build a viable company, and I think that’s a really old way of thinking,” White said. “There’s a huge number of people who need these technologies and a lot of people who can afford to pay for it and can afford to fund it. … You can have a great business model and build great products that help the world.”