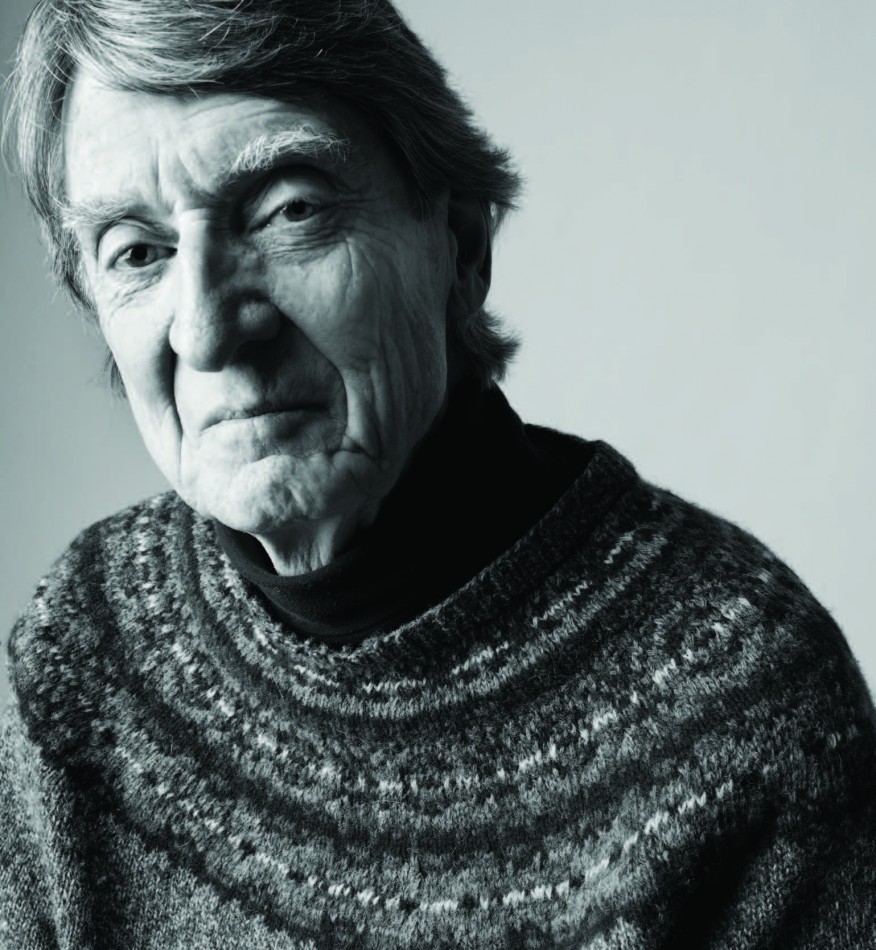

John Callahan was a graduate student researching the writing of F. Scott Fitzgerald when a literary tangent led him along a different path. In the end, it was the work of writer Ralph Ellison, not Fitzgerald, that would leave a lifelong impression on Callahan. Ellison died in 1994, leaving behind 2,000 pages of unpublished writing, an expectation that there was a second novel coming and his widow, Fanny, who eventually asked Callahan to be the literary executor of Ellison’s work. From this archive of work that Ellison left—some of it on scraps of paper and napkins—came Ellison’s posthumous second novel, Juneteenth, and Three Days After the Shooting, both edited by Callahan, the latter novel with his former Lewis and Clark student, Adam Bradley. John Callahan is the Morgan S. Odell Professor of Humanities at Lewis and Clark College. Callahan’s own writing include In the African-American Grain, A Man You Could Love, and the upcoming The Learning Room.

Tell us about your relationship with Ralph Ellison. Why would he choose a white Irish Catholic from Connecticut as his literary executor?

Ralph Ellison did not choose me or anyone else as literary executor. His illness hit him suddenly, and his last days focused on doing the tough work of facing death and being with his wife, Fanny, as fully as he could. Nor was he concerned about his writing, his legacy or anything of the kind. After his death, Fanny asked for help deciding what to do about what he had left behind, especially the typescripts and computer printouts from the long-standing novel-in-progress. I agreed to help, and once I had edited the Modern Library Collected Essays of Ralph Waldo Ellison, she asked if I would serve as literary executor. But the guts of your question has to do with my relationship with Ellison.

This is a great American story. I had read and been immensely moved and influenced by Invisible Man while I was in college. While writing my Ph.D. dissertation on F. Scott Fitzgerald, I was puzzled by allusions to the Civil War and Reconstruction in Fitzgerald’s Tender Is the Night. A close friend, the poet Michael Harper, sent a couple of uncollected essays of Ellison’s. They helped me interpret Fitzgerald and were so eloquent and fascinating I resolved to take up Ellison’s work on its own terms for its own sake. In 1977, I wrote an essay called “The Historical Frequencies of Ralph Waldo Ellison.” Still pleased with it on publication, I sent it to Ellison. A month later I was flabbergasted to receive a long letter in response, at the end of which Ellison said if I was “ever in New York and had the time he would be glad to see me.” I did and the friendship took off from there—a long liquid evening which ended about 2 a.m. with Mr. and Mrs. Ellison walking me up to Broadway from Riverside and putting me in a cab: “Yellow cab, John, always take a Yellow Cab,” Mrs. Ellison instructed me.

Ellison’s first novel, Invisible Man, is still being taught and read today. Is it still as relevant?

To pick up on your question about why Invisible Man is still read some sixty years after publication, I’ll start with Ralph’s statement in ’54 about “integration of the personality.” That’s Invisible Man’s struggle; it’s all of our struggles. And invisibility is an unsurpassed metaphor about the condition of personality in the twentieth century and now the twenty-first for the modern man and woman. Which of us truly sees another as he/she is? It’s so much easier to overlook individuality and the real work of digging beneath the superficial to discover a person and instead click another person off on some chart of demographics as Invisible Man finds that those he encounters do with him. Hell, consider Barack Obama. The response of many to him and his complexity—his blackness and whiteness. Anything and everything is better than considering him as one more individual human being with all the contingencies that go with human complexity. Then there is Ellison’s (and Invisible Man’s) eloquent writing as Invisible Man goes about the integration of personality by becoming a writer: the folk characters and their wonderful tales and set pieces, the complex fate of becoming an American as Henry James put it.

How long did you work on Juneteenth? What were the challenges in working under such high expectations?

You nailed the challenge: “high expectations.” Would the new novel be on a level with Invisible Man or Ellison’s essays? It was tough, especially as I was becoming familiar with the material for the first time, to realize how far from actual completion the novel was, as Ralph left it. Once one is familiar with all the material, a number of choices present themselves about how Ellison could have ended it. And it seems clear that, for a complex set of reasons, Ellison did not, perhaps could not, make up his mind about the book’s best shape and form. That’s part of the fascination of Three Days—and why Adam and I included a sampling of Ellison’s notes. A reader can enter the compositional process and track some of the paths Ellison could have taken as he set about to end the book. How? One novel carved out of the incomplete carcasses of three? One novel in three volumes? Like the country he loved and fought and struggled with, his second novel is an e pluribus unum riddle.

I worked for a good four plus years on Ellison’s second novel and, with Mrs. Ellison’s help, and Random House’s, came up with Juneteenth. This involved sorting out the manuscripts, computer printouts and discs and Ellison’s notes that were written on magazine subscription cards, restaurant receipts, the backs of discarded envelopes (You name the scrap of paper, he used it). When I lined it up in June-July of 1997, it was an archive, not a novel. We wanted something for Ellison’s band of readers as well as for scholars, so I took what I thought was the central story of Bliss and Hickman—the little boy who looks white, whose mama is white, whose father we don’t know and who Hickman literally midwifed into the world. He is raised by Hickman and the sisters and brothers of his black congregation, then at adolescence runs away, becomes a flimflam man on the road and on the make and resurfaces, years later as a “race-baiting senator from a New England state.” I took this story along with the prologue from Book I—always Ellison’s beginning—a few other salient passages, and the result was Juneteenth.

Tell us about call and response literature in African-American culture and what its strongest form is today.

Simply put: I to you becomes we. Artistic expression, whether in the spirituals, the blues, jazz or political rhetoric (think of Obama’s call-and-response riffs with his audiences) or, and this is the preeminent form of African-American call-and-response, the antiphony of the black church. From the beginning it’s been about black Americans’ imperative to become a people, stay a people, and put down, as a minority, cultural roots which would provide the impetus for compelling their white fellow citizens to live up to the promises made in the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. There’s a marvelous riff on this theme by Invisible Man at the beginning of the novel’s epilogue.

In your 1988, In the African-American Grain, you draw parallels between the Irish-American story and that of African-Americans. What were the similarities? How has that dynamic evolved?

I’ve known half-a-dozen fine African-American writers and to a person they’ve been fascinated by Irish culture and the Irish: the role of humor, story and music in holding an oppressed people together, and the sense that culture involves the transmission of the tribe’s experience, not as something dead but as the spirit and struggle of the past working its way on the present and the future. There’s also a sense of stoicism and the presence of tricksters in each; a sense that to survive you better know the white folks—in the case of the Irish, the English—better than they know themselves.

In New York, you’ve been collaborating on a script for a stage production of Invisible Man. When will it debut and will it make it to Oregon stage?

There is a dramatic script of Invisible Man being put through the paces of several workshops and dramatic readings over the next several months, which we expect will culminate in several full productions by American regional theaters in 2011-2012, and also likely in other countries and continents. The producer is hopeful that the production will make it to an Oregon stage, but nothing is settled as yet.

It’s your birthright as an Irish-American to run for public office. How did you settle on Eugene McCarthy and vice versa?

I came to Oregon in fall of ’67 as a young graduate student to teach at Lewis and Clark. One of the reasons I came out here was that Oregon was the only state in the union whose two U.S. senators (Wayne Morse and Mark Hatfield) were outspoken against the Vietnam War. It was a dismal time; increasing numbers of the young people and black people were turning toward militancy with violent overtones or outright violent action. Eugene McCarthy came on the scene with his, at first, lonely campaign. There was also a personal element. My father died suddenly back in Connecticut the day before Thanksgiving; we had been estranged as were so many fathers and sons. I remember coming back from the funeral, turning on the news and seeing this white-haired guy, passionate to the bone in his own quiet reasonable way (not unlike Barack Obama, by the way) make his announcement that he was challenging Lyndon Johnson for the Democratic nomination. Clearly here was a paternal figure calling Americans, especially young people, to take up a cause with long odds, which could change significant the policies and climate of the country. I came to have an important job in the ’68 Oregon campaign in which McCarthy defeated both Robert Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson, who by then was no longer a candidate but on the ballot. That led me to run in the 1970 Democratic primary against Congresswoman Edith Green, and, later, in 1976, to run as Gene McCarthy’s vice presidential candidate in Oregon—his best state, by the way. He got 5 percent as I remember.

What has the Obama presidency meant for the African-American narrative in America?

First of all, I don’t think there is really such a thing as “the African-American narrative in America.” There are too many strands. Among other things, though, Obama’s election and the immediate, pre-inauguration decision by Republican congressional leaders to shape its entire agenda around saying no over and over, carries with it, I think, overtones that this guy is illegitimate, that there’s some off and amiss about him being president, and, therefore, about whatever he does in his presidency, overtones which counterpoint the burst of pride and fulfillment that so many felt at his election. Over it all is a fact, however, the fact that he is president and somehow, as the first African-American, bears the burden of vindicating the people’s choice. So “the African-American narrative” business is also part of something else similar, maybe, to other elections and presidencies, that of Jack Kennedy as the first Catholic president and at a very young age. Kennedy’s assassination cut short the question of how he would have managed over a full term or two terms, but his presidency, like Obama’s, carried the freight of American history and culture beyond Kennedy, the skillful individual politician. The Republican strategy, articulated with chilling specificity after the mid-terms of 2010 is that it is their job to see that it’s over, that if he runs again, Obama will be defeated, and a failed one-term president. Somehow this is bound up with what kind of nation we are. Though it’s an enormous burden and challenge, Barack Obama has a chance through skill and savvy and a bit of luck to tap into currents of fluidity and change—again Ellison’s “integration of the personality.”

Tell us about what you are working on now?

I am finishing a novel called The Learning Room set on Shelter Island, New York, where I am writing right now. It pivots around the story and personality of a 5-year-old autistic boy named Fergus and how he breaks through to be himself. Interwoven are the stories of a man and a woman who come to love the boy and whom he comes to love and how each have their own secrets and troubles and tell those stories to Gabriel Bontempo, who is also the narrator of my previous novel, A Man You Could Love. The Learning Room is set in the summer of 2004. And a Ponzi schemer lurks in its pages behind the story’s climax.

One of the things I am after and that my character, Fergus, is teaching me is that to be human is to be autistic in some sense and to some degree. Through great struggle in the midst of great hurt, loss, and pain, more than anyone else in the novel, Fergus develops heroic qualities. Enough, I’ve got to go back to the writing and leave talking about it to its readers.

Wow, John. Here you are. And still teaching me, (and receiving back, were I in the room, as is your style)–so glad to find you here. I suspect you gave more to those of us who ventured out from your influence than you can ever truly know. Your voice and being fed this world through your students–myself included I would like to hope. I have so many memories…your visit to Maui among them! I send you all my best, and look forward to reading your novels, too! Grand news!