written by Anne Aurand | photographs by Joseph Whittle

On a late June day, Todd Nash bounced his dusty Ford F250 along a remote, bumpy dirt lane a few miles outside of Joseph, in the far northeast corner of Oregon. His truck jiggled through an endless expanse of sage brush and wildflowers, facing the snow-covered Idaho Seven Devils Mountains, the Wallowa Mountain peaks in the rear view mirror. There was no other human or building in sight.

Then he spotted a cluster of cattle in the distance, shut off the truck, jumped out and grabbed a spotting scope from the back. From this view—a high divide above the Big Sheep River—he looked across the patchwork of private and public land and noticed two more bunches of cattle.

“That’s unusual,” he said. Nash’s 550 head of Angus cattle were usually more sparsely spread when grazing. “Maybe something’s been through this morning.”

Earlier this spring, Nash was putting out the cow’s delicacy, salt. Nash noticed a disoriented cow whose udder was tight. He looked around for her calf, but had to hurry off to a meeting in town on the topic of wolves. When he returned, two soaring golden eagles tipped him off to the location of the calf’s carcass.

Nash had a feeling it was a wolf kill. The 48-year-old, who has been a rancher nearly his whole life, has seen a few bear and several cougar kills before, and the carnage looked different. Cougars usually eat some of the calf and drag the rest off to a ravine or a secure spot to cover it up with branches or dirt, leaving scratch marks the way a house cat covers its droppings in a litter box. This dead calf was fully consumed and its bones were crushed. “It wasn’t like a coyote had delicately went in there and bit and chewed a little,” Nash said. “It was really ravaged.”

He called the sheriff and waited in his truck—festering with anger—until Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife officials showed up to investigate.

“Getting one confirmed a wolf kill is like getting O.J. Simpson convicted,” quipped Nash, who guffaws as much as he gripes. Most of the time, Nash said, cattle just go missing and there’s nothing left to examine.

Confirming a kill as a wolf depredation requires a trained Oregon Department of Fish and Game specialist to perform a full necropsy, assuming there is a carcass. One 2003 study in the remote and rugged mountains of Central Idaho said that one of every eight calves killed by a wolf gets confirmed.

Nash estimates that he’s lost fifteen or twenty cows to wolves over the past couple of years, but he’s had just one confirmed by ODFW. These cattle can bring in $1,300 a head, he said. Losing one is tolerable, but a few add up.

There are also less tangible costs of ranching among wolves, Nash explained. Cattle that have witnessed wolf attacks have tougher times conceiving, nursing young, keeping weight on. The same dogs that cattle were trained to work with in the field, cattle begin to distrust. “Is this what life is going to be like now?” he pondered. “I hope not.”

It’s not the first time such a heated issue has arisen in this rural outpost. In the 1980s and ’90s, the endangered spotted owl controversy played out in Wallowa County, pitting environmentalists against loggers. The loggers lost, and the mill Nash worked at closed down. With the reintroduction of the gray wolf, he feels his lifestyle is under attack again.

More than sixty years after humans annihilated Oregon’s gray wolves, and fifteen years after the federal government reintroduced them in Idaho, wolves have crossed the border and settled in northeast Oregon’s Wallowa Mountains. Now about twenty wolves live in the high country around Enterprise and Joseph and they’ve been eating local livestock, calling federal and state management practices into question and fueling controversy in the otherwise quiet towns of northeast Oregon.

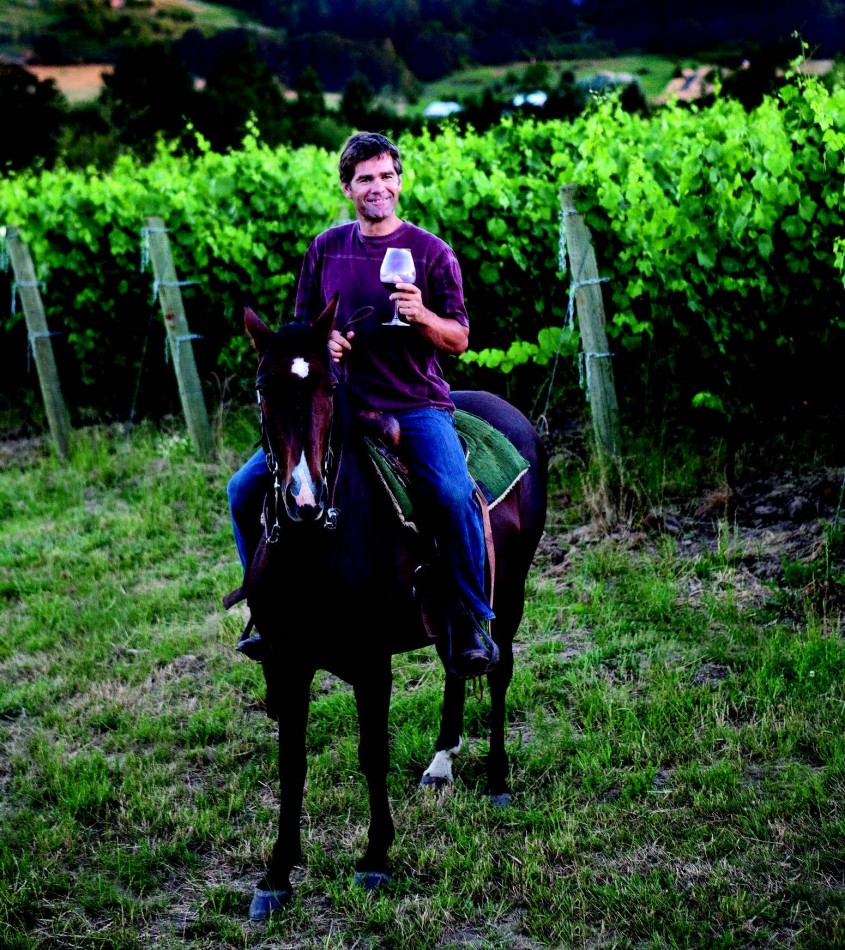

“To me, it’s real personal,” Nash said. He doesn’t want the wolves to win. Nash, who has worked around cattle since he was 6, when his family moved to Wallowa County from Davis, California, doesn’t want to make a living any other way. Cattle are his life.

The Social Balance

Firmly footed in the Old West, Joseph is largely a tourist town. Its main street is hemmed in with buildings with faux-Western facades, blooming flower arrangements, brewpubs and bronze statues. It’s home to several bronze foundries and a disproportionately high number of artists and art galleries.

As art galleries opened, the region began recreating itself on canvases and in bronze statuary. Last year, there were twice as many jobs related to leisure and hospitality than in natural resources, which includes ranching.

The presence of wolves, however, has tested the social balance in this otherwise peaceful warren. One well-known and vocal rancher slammed his fists on tables in public meetings about wolves. One business owner in the area was too afraid of offending some hostile neighboring ranchers to speak out in support of wolves.

Letters to the editor published in Wallowa County Chieftain conveyed a prevalent hatred of the wolves from locals.

In a June 17 letter to the editor from Enterprise resident Rod Miller titled, “No ‘Wolf’ in Constitution,” Miller took the hard line against wolves. “Sportsmen, hikers, businessmen and ranchers need to come together and tell the government that enough is enough, remove your pet project and your unwilling cooperation from our lives,” he wrote.

Miller’s letter drew this string of responses on the newspaper’s Web site.

“Your game populations will suffer, then on to livestock, your dogs and cats, then you and your children. If anyone thinks they stand a chance of fighting off a wolf [sic] unarmed, think again,” a respondent named Leonard said.

Marty retorted: “It is amazing to me after reading some of these posts, that wildlife ever managed to survive for 1000s of years before the lord and master ranchers arrived to save them from the horrid wolves.”

Finally, T, navigated the middle ground: “I hope this can all work itself out. I want private property owners to be able to protect their livestock on their property. I also would like to see all ranchers stay in business and I would like to see wolves in the wild of Oregon again. My hope is that everyone will look at the true facts, not just the assumptions that best serve one group.”

One long-time local gallery owner, who didn’t want his name used because “it’s a politically hot issue and times are tough,” said his untested theory is that paintings of wolves aren’t selling these days. He didn’t remove wolf paintings from his gallery, but he stopped painting new ones. “It’s like painting pictures of terrorist bombers from Al-Qaeda,” he said.

Wolves haven’t hurt his business, he said, the economy has. But he sympathizes with those more directly affected by wolves. There’s a pervasive fear about things changing, he observed. “Wolves are beautiful, but what’s more beautiful is a family able to feed their children,” he added.

Retired charter boat sailor Wally Sykes, who has lived in the mountains near Joseph for about fifteen years, has seen wolf tracks near his property but has never seen a wolf. His neighbors have heard their hair-raising howls.

“I think that on an ethical basis, it’s wrong to eliminate an entire species for what amounts to the convenience of special livestock interests,” Sykes said.

He has written pro-wolf letters to the editor of the local paper, pasted Defenders of Wildlife stickers on his car and has worn wolf shirts in public. As provocative as that may seem in a small town, Sykes said he has not experienced any overt hostility. “No one has keyed my car,” he said.

Wolves Reintroduced

Though Wallowa wolves are the firebrand of recent controversy, this saga began in Idaho fifteen years ago. In 1995, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service imported several dozen gray wolves from Canada and reintroduced them in Yellowstone National Park and Central Idaho’s 2.3 million-acre Frank Church River of No Return Wilderness.

After wolves had been virtually exterminated from the Lower 48, the 1974 Federal Endangered Species Act protected the Rocky Mountain gray wolves and required that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service try to recover them.

Various polls and surveys showed that a majority of people across the country wanted them back. Supporters applied enough political pressure to make it happen. Many of these people who favored the reintroduction of the wolf cited wolves as a natural and necessary predator for booming populations of elk and bison in Yellowstone or expressed a moral imperative of preserving “God’s creatures,” according to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s environmental impact statement.

At that time, gray wolves were known to occasionally wander across the border from Canada, said Ed Bangs, U.S. Fish and Wildlife’s wolf recovery coordinator, who spent thirteen years tracking and hunting predators in Alaska before moving to Helena, Montana, to oversee the historic and controversial reintroduction.

They would have moved into the United States on their own in about fifty years without the reintroduction program, Bangs estimated. Instead, the federal agency hastened to rebuild the wolf population so that the government could remove their “endangered” status. This would also allow wolves to once again be hunted, either for sport or in defense of livestock. “Fish and Wildlife Services recognized that regulated public harvest is a valuable wildlife management tool,” the 1994 environmental impact statement said. “Public harvest can be one of the most efficient, inexpensive, and locally acceptable methods of managing wolf populations and minimizing wolf-human conflicts once wolf populations are recovered and delisted.”

Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf?

Public harvest—when combined with demonizing fables—can also be the most efficient method of eradication. The plight of the wolf goes back at least as far as the Middle Ages, when wolves and farmers fought for precious territory. European emigrants brought their hatred of the wolf to America in the 1500s and 1600s, when wolves roamed most of North America. Through myths and fairy tales such as “Little Red Riding Hood” and “Three Little Pigs,” wolves were culturally demonized. A generational fear of wolves was seeded in America.

The American West, however, was big enough for another perspective on the wolf. In many Native American tribes, including the Nez Perce who lived in Joseph and in Central Idaho, wolves and humans complemented each other and coexisted naturally. Nez Perce warriors wore a wolf tooth pushed through the septum of their noses. The early French settlers who encountered them, called them the nez percé, or pierced nose.

Horace Axtell, a Nez Perce elder was born and raised in the village of Ferdinand, Idaho, served in World War II, has worked as a forester and is now a spiritual leader in the Nez Perce Seven Drum religion. The Nez Perce feel connected physically and spiritually to the wolf, he said. Theirs is a world in which large predators are part of a functioning, interconnected environment. Axtell is happy to see the wolves return to Idaho, but it’s painful for him to see them hunted.

The 85-year-old was a child when Idaho’s last wolves were killed. Back then, he listened to stories from his elders about what it was like coexisting with wolves. One story he quickly recalls. When his people were camping out and hunting deer and elk, they would hear a wolf howl. In the morning, a hunter would walk to where he heard the sound, and there would be a buck, and the hunter would kill it. The wolves of Nez Perce lore, contrary to European fables, helped the Nez Perce find their food.

As America was settled, native prey like bison and elk declined, domestic animals such as cattle grazed the land, and wolves turned to new sources of food. The first American wolf bounties came in the 1600s, and were payments of cash, tobacco, wine and corn. In ensuing centuries, government agencies and private citizens eradicated wolves across the country, shooting, baiting, trapping, and poisoning them by lacing dead buffalo or cattle with strychnine. Some accounts say as many as two million wolves were killed in the last half of the nineteenth century.

It was also in that era that the wolf played an important role in bringing together people of the Oregon Territory and eventually statehood. It started when cattle baron Ewing Young died in 1841, with no heir for his fortune. After Young’s funeral near Newberg, his neighbors met and put together a governing body to process his estate, and one which would lead to Oregon statehood. They held more meetings to manage Young’s wandering cattle, which were being attacked by wolves and mountain lions. An Oregon Wolf Association meeting in 1843 set a $3 bounty for a large wolf. Oregon’s last bounty-killed wolf was recorded in 1946.

The Wolf Reconsidered

The twentieth century brought a dramatic shift in attitude toward the wolf, both symbolically and scientifically.

Particularly influential were the writings of conservationists such as ecologist and author Aldo Leopold (1886 –1948), who wrote, “I have lived to see state after state extirpate its wolves. I have watched the face of many a newly wolfless mountain, and seen the south-facing slopes wrinkle with a maze of new deer trails. I have seen every edible bush and seedling browsed, first to anaemic desuetude, and then to death. I have seen every edible tree defoliated to the height of a saddlehorn. Such a mountain looks as if someone had given God new pruning shears, and forbidden Him all other exercise.”

More than fifty years after Leopold’s death, a team of researchers from Oregon State University tested his observations about wolves’ role in a functioning ecosystem. Ecologists William Ripple and colleague Robert Beschta published numerous studies illustrating the relationship between predators, herbivores, plant life and a healthy ecosystem. They concluded that within a few years after wolves were returned to Yellowstone, elk populations fell and elk behavior changed. The presence of wolves kept elk and other grazing animals on the move, therefore preventing them from overgrazing riparian vegetation. Pockets of trees and shrubs rebounded, beavers returned, coyotes waned and fish and bird habitat flourished.

This shift in attitude found political expression under the Clinton Administration. After decades of debate about wolf reintroduction, the 1994 environmental impact statement said wolves would survive in Yellowstone and central Idaho, and they would reproduce and expand their territory. Secretary of Interior Bruce Babbitt took this report and presided over one of the most ambitious projects ever undertaken by that office.

The environmental impact statement drew more than 160,000 comments—the largest response to any action ever proposed by the Fish and Wildlife Service.

Over the course of two years, the agency held sixty-one open houses, twenty-two public hearings, and more than thirty presentations to interest groups in the affected areas and around the country.

Oregon’s Department of Fish and Wildlife “was not at the table when the discussions began about the reintroduction of Northern Rocky Mountain wolves,” said ODFW spokeswoman Michelle Dennehy. “Oregon was considered as a potential reintroduction site for wolves, but due to the fact that we have few unsettled … wilderness … areas, Oregon was not included as a candidate for release when the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service put their plan together. Oregon began planning for wolves … after wolves arrived.”

By 2000, the wolf population in Wyoming, Montana and Idaho had reached the USFWS’ recovery goal of 300 wolves and thirty breeding pairs for three successive years. As wolf populations grew and rambled outside the public lands around Yellowstone and central Idaho, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service modified its wolf management rules in 2005 and again in 2007, each time liberalizing the power of residents to shoot wolves. More than 1,700 gray wolves now live in the Northern Rocky Mountain region, according to 2009 numbers from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife. Of those, 913 were in the central Idaho area. Last year, the federal agency reported that wolves were the confirmed killers of 214 cattle and 721 sheep in the Northern Rockies region.

While the federal government oversaw a bold reintroduction of the gray wolf, it was less prolific in its plans to compensate those affected by the wolves. Instead of setting up a government-administered fund, Fish and Wildlife Services relied on the member-based nonprofit and wolf reintroduction proponent, Defenders of Wildlife. Defenders of Wildlife took the responsibility of reimbursing ranchers for depredations and paying some costs associated with preventative measures. The nonprofit’s twenty-three-year-old reimbursement program, however, ended abruptly in September putting the onus of compensation on individual states.

Defenders of Wildlife said it would continue to work with ranchers to implement preventative measures to reduce the carnage. John Faulkner, a sheep rancher from Gooding, Idaho, since the 1940s, has resigned himself to living in wolf country and has tried, somewhat successfully, to reduce the loss of sheep through methods that Oregon ranchers are now just testing. Faulkner started losing sheep about four years ago, he figures around a hundred a year, although only a small number of those get confirmed as being killed by wolves, he said.

Guard dogs have helped run off younger lone wolves. At night, his herders shoot guns into the air or set off firecrackers to scare them off when telemetry tracking shows collared wolves are nearby. He has also deployed giant spotlights at night. “That’s one tool I like pretty well,” said Faulkner. “You can light up the whole countryside. Everything works sometimes, but not always for sure. After a while wolves get wise to people, and they get hungry.”

Most effective, he said, was when wolf hunting was legalized in Idaho. “It changes wolves’ behavior and comfort around men.”

Bangs, the USFWS wolf recovery manager who has watched this process play out in other states for fifteen years, said Oregon will probably never have the kind of wolf populations that Idaho does, because Oregon is a more developed landscape.

But this debate is more about the people than the actual wolf, Bangs noted. Wolves symbolize different sets of human values. He expects that neither set of beliefs will change, but the hysteria will eventually fade.

“You can only stay really upset for so long,” he said. “Because it’s new, no one (in Oregon) has any real experience, so you get these highly polarized viewpoints by both sides. We go through this same thing over and over and over and it’s now just Oregon’s turn.”

Obviously the author has never been on The Divide above Big Sheep because there isn’t any “sage brush” there! Makes me question the rest of the story.