The Science of Art

written by Amy Korst | photos by Peter Mahar

Illustrator Sienna Morris has designed a home and workshop in Portland so reflective of her style that it’s difficult to tell where she ends and her art begins. Art pours out of two upstairs rooms in her Portland home, and her basement serves as a workshop for stretching canvas, printing illustrations, and carefully packaging paintings and drawings for shipment to faraway places.

“You find art in the body and unexpected places,” Morris said, explaining her unquenchable sense of wonder and never-ending exploration of science and the natural world.

She serves tea on brain coasters while her tuxedo cat, Mr. Moore, wanders among the treasures collected in a room that is part scientific laboratory and part artist’s studio. A mini fridge of mammalian eyeballs waits in one corner next to her two microscopes, affectionately known as Kirk and Dune. A locked plexiglass case contains specimens Morris will study further, including several vertebrae from an animal skeleton she found on a recent hike. She stacks finished artwork along the wall, including illustrations selling for thousands of dollars.

Her work in progress dominates one side of the studio, a depiction of the jellyfish species Pelagio noctiluca, or deep sea night light. This artwork—part painting, part drawing, part something else entirely—depicts a jellyfish floating against a background of blues and purples, a sea creature caught inside the shifting clouds of an outer space nebula. Beneath a black light, the jellyfish glows, thanks to Morris’s use of pearlescent ink, an effect that cleverly mimics the jellyfish’s natural bioluminescence.

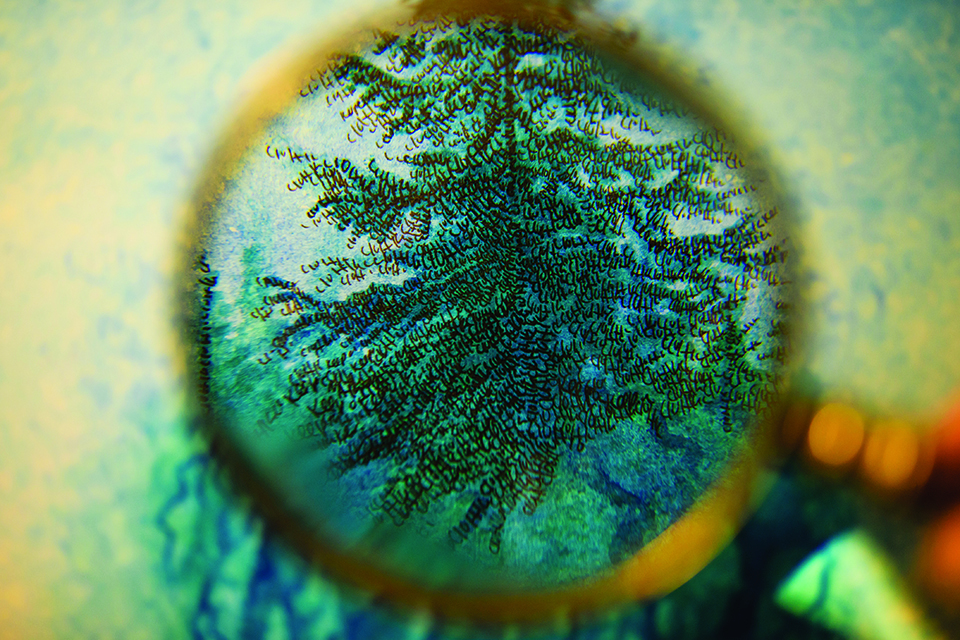

What makes Morris’s art so unique is her technique, which she has dubbed “numberism” (a play on pointillism, a technique of painting in minute dots). Instead of drawing in dots, Morris’s numberism pieces are created from tiny numbers repeated over and over. Sometimes, the numbers are so small and tightly packed together it’s hard to tell they are actually there at all without the use of a magnifying glass.

Sienna Morris’s numerical creativity

Morris creates her pieces using the tiniest imaginable blades to etch numbers into scratchboard, or particleboard covered in white China clay that is then painted over with black India ink. Once her images are etched into the scratchboard, she uses a combination of artistic techniques to add color and texture to her images.

The numbers Morris uses in her art relate in some way to the subject she is depicting. For example, the jellyfish is drawn with the chemical formula for luciferin, what makes them bioluminescent.

Morris created numberism during a time of reinvention in her life. She had just moved back to the United States from China after a multimedia company she had a part in creating failed. “I felt like a complete failure and that all my choices had been wrong, and I had no faith in myself,” she said. “I felt defeated.”

At a time of great anxiety and personal upheaval, Morris began drawing with the numbers on the clock, trying to capture the forward march of time. “I understood I needed to be present, but I didn’t know how to do it, so I drew these moments,” she explained.

And like the proverbial phoenix rising from the ashes, Morris successfully reinvented herself, drawing images for herself instead of for others. Her first numberism piece is called “Falling To Pieces,” and it depicts the moment just before a kiss, two pairs of lips a whisper away from each other.

“That was to capture how a moment actually felt, which is like a breath,” she said. “I imagine the feeling is like holding sand that’s falling through your hand.”

Morris drew with the numbers on the clock for two years, capturing those ephemeral moments, before turning to the world of math and science for new numberism inspiration. Morris, who has very little formal art training and no background in science, is self-taught and follows her passions wherever they take her. She is particularly fascinated by the brain and linguistics, evidence of which is scattered throughout her home, as her bookshelves are filled with science textbooks and her compound microscope cradles a glass slide of motor nerve cells.

Microscopic artistic inspiration

“Very rarely have I put something under this microscope that hasn’t been inspiring, that hasn’t been beautiful, that hasn’t given me perspective that I couldn’t have gotten elsewhere,” Morris said.

In various pieces, Morris has used the chemical formula for oxytocin, the standing wave pattern of a single plucked cello string, and the Fibonacci sequence. One of her favorite pieces hangs on her living room wall, titled “Corvus Callosum,” depicting a crow perched on a walnut, atop a background of a pyramid neuron.

Morris comes from a family of artists and decided at age 7 to become an artist herself. She reaffirmed this choice in early adulthood when she took the leap of moving to Portland, a community notoriously friendly to the arts, to pursue her calling.

“I decided to make it as an artist or else,” she said. “And or else meant eating ramen and peanut butter or being late on rent for months at a time.”

Today, she runs her business, Fleeting States, out of her Portland home. She can be found at the Portland Saturday Market in booth 904 from March to December.

Next check out the work of sculptor Alison Brown.

Take a look at Dave Dahl’s new African Art business.

Richard Taylor applies art principles to the science of sight