written by Amy Faust | photos by Talia Galvin

Every spring for almost thirty years, Bruce Mate makes his way down to Baja to reconnect with the same female gray whales. Over four decades, he’s witnessed their transition from smooth-skinned youth into mothers. More recently, he’s seen wrinkles start to appear around some of their eyes, each eye roughly the size of a baseball. He’s met and played with their offspring, even seeing some from the next generation become mothers themselves. These whales feel like family to him.

As director of OSU’s Marine Mammal Institute, Mate has crisscrossed the earth’s oceans, studying almost every type of whale, from humpbacks to right whales to elusive blue whales—the largest creatures ever to live on earth. He shouldn’t play favorites, he said, but, gray whales are at the top. After years of observing them and guiding trips into their habitat, Mate has seen them charm everyone they meet by eagerly swimming up to greet boats, relishing human touch and showing off their calves like proud human moms. “They’re the only whale species in the world that does these things,” he said. “t” Mother whales don’t sleep at all, Mate surmised. They see tour groups as “boats that happen to have hands” and a perfect opportunity to temporarily hand off their demanding young.

Mate is somewhat of an ambassador himself. As a pioneer in the field of tracking ocean creatures’ migration, feeding and breeding patterns, he has unearthed new data about virtually every type of whale, answering questions to many of the great mysteries surrounding these endangered creatures. In almost forty years of work, he has helped humans understand whales in ways that are shaping policy and nurturing population growth.

An unusual combination of engineering skill and passion for sea creatures made Mate a valuable ally to whales. As a self-described “geeky” middle schooler in Illinois in the early 1960s, his fascination with high-tech communication led to a Morse code chat with Russian cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin, the first human in space. A few years later, when a biology teacher at Mate’s landlocked high school brought pickled marine specimens into class, a lifelong fascination was born.

After college, while studying at a marine station run by the University of Oregon, Mate was “incredulous” that no one had ever figured out a way to trace the migration patterns of sea lions. So he set out to tackle that challenge, and united his love of technology and ocean creatures.

Using radio tags (devices that emit a sonar “ping” that can be picked up within about a five-mile radius), Mate began tracking harbor seals and sea lions. When his fellow researchers saw the data he was gathering, “they told me, ‘If you could ever do this with whales, it would be huge, because we don’t know a thing about their migration patterns either,’” he said. Mate, then a faculty member at Oregon State University, lobbied for funds for whale tracking. His pleas fell on the deaf ears of a community that refused to believe any kind of device would stay put on such a giant creature.

Mate’s wife, Mary Lou, his girlfriend since the seventh grade, was not as skeptical. She sold her car, took out a second mortgage on their house and asked him, “Now what’s your excuse?”

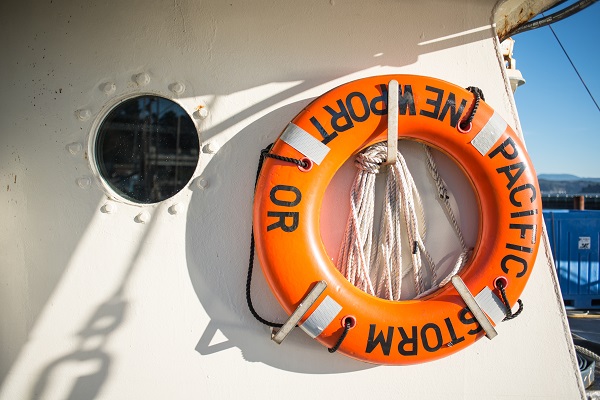

In the summer of 1979, the Mates and their two young children vacationed along the Baja California, Mexico coastline to test Mate’s idea. After successfully tagging three gray whales, they returned home, leaving the only receiver with friends in California. When these friends started hearing pings, Mate was encouraged and quickly had them mail him the receiver. No longer able to stand the suspense, he flew an airplane along the coast a few weeks later and picked up even more transmissions. When one of Mate’s tagged whales made it all the way to Alaska with its tracker intact, a new branch of marine mammal studies was born.

Funding soon poured in for this new research, and Mate and his team from OSU were able to tag and trace the habits of whales all over the world. This provided plenty of surprises. “In most cases, we’d had a fundamental misunderstanding of what these creatures were doing for a living,” Mate said. As technology evolved from radio to satellite to hybrid GPS devices, Mate and his colleagues can now follow these mammoth creatures into remote parts of the ocean where they have bred and fed for millions of years, unobserved by humans until now.

In Kingdom of the Blue Whale, National Geographic’s most-viewed documentary, Mate and a team of researchers are shown seeking these elusive giants off the coast of California and implanting them with small transmitters to track their movements. When the scientists successfully reunite with the tagged whales in the ocean off Costa Rica, they finally solve the mystery of where these endangered animals are giving birth.

This information didn’t just satisfy the curiosity of marine mammal researchers, it became a vital tool to help preserve species. Once breeding grounds are discovered, they can be protected as a habitat, as is the case with the waters off Baja California, Mexico, where gray whales give birth. In just a few generations, gray whales have gone from being hunted to thriving, successfully breeding their way off of the endangered list.

As for the still-critically endangered blue whale, Mate and his team have recently discovered that many are being killed by ship strikes off the California coast. Mate said that when shipping companies are informed that they can help save an endangered species by simply reducing their speed in a designated area, they’re generally very receptive.

Some fascinating whale tales have emerged from Mate’s research as well. One pair of whales that caught the world’s attention was Flex and Varvara, two of just 130 Western Pacific gray whales in existence. Once Mate tagged them in 2011, people in more than sixty countries tuned in to track their migration via the internet. Traveling separately, Flex and Varvara surprised their followers by leaving Russia and heading not to the South China Sea as expected, but east to Alaska and down the coast to Baja, where their non-endangered western counterparts had found sanctuary.

Perhaps the most prominent “celebrity whale” that Mate is involved with is so-called 52, dubbed “the loneliest whale in the world.” Discovered by naval technicians in the ’90s using sonar originally meant to detect Soviet subs, 52 is unique because it vocalizes at a much lower frequency—52 Hertz—than any whale ever recorded. As these technicians recorded this whale year after year on its trips from Alaska to Mexico, they never heard another whale respond to its call.

While the elusive 52 has caught the attention of marine scientists—who remain unsure what type of whale it is—52 has become an object of fascination for people all over the world who have taken his narrative and shaped it into something meaningful to them. Musicians, poets, writers—even Taylor Swift—have something to say about this animal. The overriding theme is that of a whale that is a tragically misunderstood loner, unable to find love or companionship. Actor Adrian Grenier is producing a documentary about him, and has asked Mate and his team to help find 52.

At first, Mate refused. “I didn’t want to waste my time looking for one whale just to satisfy people’s curiosity,” he said. Further, Mate is not convinced of the “lonely whale” storyline. “I suspect that if we find him, he will be in a group with other whales, and we will find that his unique vocalization is caused by something like the whale equivalent of a cleft palate. Just because it’s different doesn’t mean other whales can’t understand it.” Ultimately, Mate has agreed to help find 52 as long as he can also tag a dozen more whales, making the findings more scientifically relevant. His team will try to intercept this famous whale next fall with cameras rolling.

During Mate’s forty years with OSU, what started out as essentially a one-man program has evolved into a fully endowed, highly regarded institute. With an emphasis on using cutting-edge technology to study and ultimately help save a huge variety of ocean creatures, the Marine Mammal Institute (mmi.oregonstate.edu) is a reflection of Mate’s passions. In more ways than one, he has his favorite whales to thank for this. Not only did they provide the very first tracking data back in the 1970s, but they continue to provide entertainment each year when Mate brings groups down to Baja for interactive expeditions. He estimates that about 80 percent of the $8 million endowment for the institute comes from people who have been on one of these trips.

For many, this expedition is life changing, said Mate. “People are very emotionally struck by the intimacy of a whale looking at them. Some people feel like these animals are looking right into their souls, and they come back with a new understanding, not just of whales, but of the importance of maintaining habitats where our fellow creatures can relax, breed and safely live”

At nearly 69 years old, Mate said he’s spent enough time on boats and is happy to focus more on fundraising than field work. His passion for the subject makes him an ideal champion for the cause of whale conservation. “What the big ‘charismatic megafauna’ like whales do is help us come to grips with our interconnectedness,” he said. “If we start to care about one endangered animal, we begin to realize all of the things that animal needs to survive, and, ultimately, how important it is to protect the whole food chain.”

In forty years of chasing giants, Mate’s sense of wonder is undiminished. “When you’re out there on a twenty-foot boat waiting for a blue whale to come to the surface, you see this little shimmer of light gray that turns a different blue than the water, and pretty soon the form gets bigger, and you realize it’s probably four times the size of your boat. You’re looking at the largest creature that has ever been on earth, and it takes your breath away.”

Bruce, I am wishing you many more articles like this one that gives the full picture. If every reader contributed the whales would be very happy. Keep up the good work.