written by Katie Chamberlain

photography by Thomas Boyd

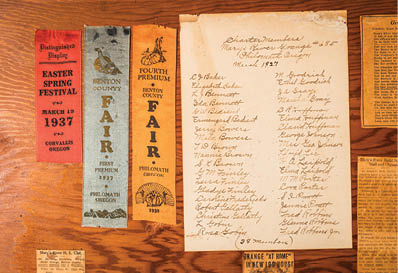

ON A DRIZZLY OCTOBER MORNING, Jay Sexton dug through the archives of Marys River Grange with a quiet enthusiasm to show me the roster and photos of the grange’s original members, and poems describing the tightly knit grange community.

Founding members of this grange, located in Philomath, heaved logs donated from nearby mills to construct the log cabin hall over several years in the early 1930s. The grange is tightly woven into the community’s landscape: Many of the nearby roads were named for families who were active in the grange during its early years.

These historic halls, dotting Oregon’s back roads from Sixes to Enterprise, offer a window into Oregon’s agrarian past—and a glimpse into modern rural life. “People think of us as the building, but it’s more than the building,” said Sexton, steward of Marys River and state grange overseer. Sexton, a retired forest ecology field technician, grandfather and avid gardener, joined the grange in 2010. Like a growing number of modern-day grange members, he’s not a farmer.

Later that morning, two young men pulled up and began unloading equipment. Sexton paused. “It could be band practice.” Then he remembered it was the monthly health clinic for uninsured farmworkers, sponsored by neighboring Gathering Together Farm. He lit a fire in the woodstove in the front of the hall to start warming up the room, and the volunteers began setting up curtains and beds. Sexton said the grange provides the hall free of charge for the clinic and Gathering Together rents the materials and coordinates volunteer doctors and nurses.

Across the state, granges like Marys River have sustained a modern presence by adapting to meet the needs of Oregon’s rural communities. This manifests in events like the monthly farmworker health clinic in Philomath and barn dances outside Eugene. The shifting demographics in rural communities—younger and more progressive—have infused the organization with new energy in the past decade. Simultaneously, this shift has created new dynamics on the local and state levels as the nonsectarian, nonpartisan organization tests its capacity to make room for a wider spectrum of values.

Oliver Kelley, a Minnesota farmer and activist, founded the grange in 1867 as a national fraternal organization to represent the views of rural residents and the agricultural community. Kelley contended that farmers would benefit from an organization representing their interests, due to their independent and scattered nature. He also integrated rituals and a fraternal element—similar to the Masonic Lodge—into the grange culture, which lives on today. “In these modern times, when a person joins the grange, they are automatically at the fourth-degree level (of seven degrees total),” Sexton said. The traditional ritual for the first four degrees takes about four hours, and Sexton described it as a non-religious passion play with lessons from the natural world.

A true grassroots organization, grange initiatives have filtered up from the community level to broadly impact rural life, both locally and nationally. Grange resolutions and lobbying efforts, for example, have led to improvements in rural fire protection, postal service and utilities as well as the creation of state agriculture schools, the Extension Service and 4H. Early grange leaders also recognized the importance of social interaction for rural residents. Today, the National Grange seeks to provide “opportunities for individuals and families to develop to their highest potential in order to build stronger communities and states, as well as a stronger nation” through fellowship, service and legislation, according to its website.

Marys River is one of 167 current active granges in Oregon. At the grange community’s peak in the 1940s, Oregon supported 371 active granges. While the emphasis on agriculture has diminished slightly over the years, it also seems to be one possible key to the organization’s renewal. Broadly, granges continue their strong tradition of serving the needs of their surrounding rural communities, many of which retain agrarian roots. At a recent retreat, Oregon’s state officers defined the grange as “a community organization that answers local needs.” Sexton provides more context. “The reason that’s important is that every grange is idiosyncratic,” he said. “We have a 150-year history of promoting local foods and non-sectarian, nonpartisan face-to-face community.”

In many grange halls, shared meals and food remain a primary avenue of this face-to-face connection. Spencer Creek outside Eugene hosts a popular pancake breakfast every summer and a chicken barbecue in the fall. Hood River’s Rockford Grange host monthly “Crop Talks” where area farmers come together to share a meal and network. Grange halls from Smith River to Dorena fill with community members for monthly pancake breakfasts and potlucks.

Dawn Merila joined the Smith River Grange twelve years ago, just after she and her husband moved to a 300-acre riverside ranch where they farm hay, raise cattle and sell timber. The Smith River is lined with similar properties, ranging in size from 100 to 500 acres, and the nearest neighbor may be 3 miles away.

“These rural communities are pretty family-driven,” Merila said. “It occurred to me that the best way to get familiar with the community was to join the grange.” She introduced herself one Saturday morning and asked how she could help. At the time, the grange had just lost the “egg lady” for the monthly pancake breakfasts and Merila happily stepped in. “Eleven years later, I’m still making eggs,” she laughed.

The Smith River Grange Hall is located 9 miles from the nearest town of Reedsport and regularly serves 120 people at a monthly pancake breakfast. “It’s a great way of coming together and catching up on the goings-on,” she said.

Beyond potlucks and pancake breakfasts, granges have adapted to meet the increasingly diverse interests of their communities—and reveal each grange’s character. At Rockford, the events calendar stretches far and wide—art workshop, contra dance, interfaith meditation, seed-saving workshop and book club. Spencer Creek hosts a popular haunted house, a holiday bazaar and a Christmas program each year, according to lifelong members Malcolm and Cookie Trupp, now in their 70s.

Community service remains a strong thread in the grange ethos statewide. Marys River donates backpacks and school supplies to local schools, organizes food drives, has gifted new truck tires to a local veteran, and sponsors meetings for organizations with similar goals. Smith River’s thirty members, primarily longtime residents and loggers, use the funds raised from the pancake breakfasts to sponsor a local high school girls’ softball team and routinely donate between $500 and $1,000 to residents who encounter unexpected hardships. “These small communities really come together,” said Susan Noah, state master and a lifelong grange member. She said the Barlow Gate grange in Wasco County raises nearly $25,000 each year for scholarships for local children through its annual dinner and auction.

However, like many community-based organizations, grange membership has declined in recent years, Noah said. “Our grange wanted to close in 2009 due to a lack of membership, and more importantly, a lack of hope,” Sexton said. He was among the fifty members who joined in 2010 to revive Marys River in a push led by longtime farmers John Eveland and Sally Brewer from Gathering Together Farm. Marys River continues to actively recruit new members and has maintained a strong membership of approximately sixty in recent years.

Before the Marys River renewal effort, the average age for members hovered around 70, with very few active members. Now, the grange has approximately fifteen members who are in their 20s, and the average age has dropped to 35. Many of the new members have direct connections to the local food industry, including young farmers, an artisan meat smoker and a producer of organic livestock food.

“The granges I see growing are involved in their communities, have younger members [in their 40s and 50s, or younger], and are more involved in how food is grown and where it comes from,” Noah said. Following a statewide membership drive for the 150-year anniversary in 2017, Oregon granges increased by 200 members statewide and now total 4,700. Over the last decade, these recruitment efforts have attracted younger, more progressive members to an organization rooted in traditional agriculture and values.

Genie Harden raises dairy sheep, a cross between East Friesan and Lacaune, and grows vegetables on a 20-acre property off Lorane Highway that winds through pastoral rolling hills southwest of Eugene. She joined the nearby Spencer Creek Grange thirteen years ago, when her now 15-year-old daughter was a toddler, with the goal of meeting like-minded parents.

As a new member, she started a family film night, which ended up attracting more elderly residents than children. She pushed for the annual pancake breakfast to begin using locally sourced food and revived the now-thriving barn dances in the grange hall. “I was inspired by an old painted sign advertising the Old Time Fiddlers from the 1980s,” she said. “It captured my imagination.”

The barn dances have a storied history at Spencer Creek and regularly draw families from across the county. “The grange has many functions in the community and historically has supported agriculture,” said Stephanie Schiffgens, a grange member who raises Gotland sheep on nearby Appletree Farm. “[The barn dances] offer a way to get to know neighbors and provide a safe environment for families in our community to come together.”

Since its inception, the grange has held space for civil discourse through a nonpartisan, non-sectarian frame. Women have always been full and equal members of the grange, rights that preceded the national suffrage movement. At annual state sessions, delegates can introduce resolutions created at the community granges for adoption at the state level. “I feel like our state sessions are very congenial,” Noah said. “We enjoy our parliamentary procedure.”

Sexton identified Marys River as an active, progressive grange that’s trying to be relevant and make a difference with local food and community. To this end, Marys River actively initiates resolutions, from a prohibition on gerrymandering to allowing grange hall renters to serve alcohol at events. Other local granges, like Smith River, tend to stay out of the policy arena and focus primarily on providing a community touchstone.

However, the integration of newer members, who often hold opposing values and political views to the traditional grange culture, at times proves rocky. “We have to work with different, newer ideas that didn’t come on the floor in the past,” said Cookie Trupp, currently lady assistant at Spencer Creek and state lecturer. “It’s about learning how to work together and disagree, or agree to disagree and leave still being friends in the grange.”

It’s an organization where ranchers and passionate environmentalists debate contentious policies such as wolf management, pesticide usage and GMO policies. “We’re a perfect microcosm of this country,” Harden said. “But [the grange] offers a structure for our country to heal. It was designed that way from the beginning.”

Harden also started the Spencer Creek Growers Market, a weekly farmers market at the grange hall and an independent nonprofit. She later delved into the grange’s legislative sphere, navigating political tensions at Spencer Creek and, later, during Agriculture Committee meetings at the state grange sessions on issues ranging from the organization’s position on GMOs to the management of wolves in Eastern Oregon.

The tension is not always easy to hold, however. Harden did not renew her grange membership last year, though she still continues to manage the Spencer Creek Growers Market. “I still thoroughly believe in the potential of the grange to heal our nation,” Harden said. “Our struggles are indicative of so many.”

On a warm Friday evening in late September, a well-loved local caller, Woody Lane, gave rapid-fire instructions for a square dance at the Spencer Creek grange hall. Children and teenagers joined hands and formed small circles with adults, deftly switching partners and spinning happily. Dizzy and flushed, the dancers collapsed onto wood benches lining the dance floor as the song ended, catching their breath before the next dance. The atmosphere was light and welcoming—the spirit of the grange filling the well-worn dance floor.