written by Jeremy Storton | illustrations by Michael Williamson

At 1859, we encourage the beer sip, the swig, the beer flight and beers that bring adults together for good, reflective times. Let’s get to the bottom of why Oregonians love beer and become a little more knowledgeable in the process. As a bonus, we’ve empowered you with a beer-food pairing guide at the end. Drink responsibly. Cheers!

Brewers began ditching the large and lifeless lagers for British-inspired DIY brews full of craft and flavor. It was Oregon, then, with its pioneering attitude, which forged new trails in pursuit of something better in the form of food, wine, coffee and, of course, beer. “I think Oregon has a really independent, entrepreneurial, artisan streak that’s just in us,” said Brett Joyce, president of Rogue Brewery. “Part of what that provides to us as Oregonians is we look for connections with the products that we consume. I really think we embrace and celebrate authenticity and creativity, and all that comes through in craft beer.”

The craft beer momentum within the Pacific Northwest, and especially within the Oregon borders, continues to thrive. During 2015 the country’s wine sales topped out at around $38 billion, whereas beer sales raked in almost $106 billion.

When Oregon ranks number two for breweries per capita, it creates a certain responsibility. “Oregon continues to lead, there’s no question, but the rest of the country is on to it,” Joyce said. “Portland has the greatest craft beer market share in the country. There are numbers to back up the fact that Portland is `Beervana,’ and the rest of the country is playing the game of catch up.”

Perhaps feeling the leadership charge, in 2013 the Oregon State Legislature passed OR Bill HCR 12, which made Oregon the first state to have an official state microbe—Saccharomyces cerevisiae (brewer’s yeast). “The fact that people travel and come to Portland really, I think, showcases the fact that the world of beer is looking to Oregon and to Portland for leadership and inspiration,” Joyce said.

Randy Scorby, Grand Master III Beer Judge, agreed with Joyce’s sentiment of Oregon’s distinction as a mecca for beer. “It wouldn’t surprise me if it had a lot to do with the wine industry that was already here. Wine was already really taking off and had a real strong foothold when the craft beer industry started. So you had people with really developed palates who knew what they liked.”

The rise in the quality of food, food carts, artisanal cheese, curly mustaches, craft beer, music and espresso shops have become finely tuned cultural and production processes in Oregon. “In this whole outdoor, left-coast lifestyle, we see the artisanal food movement kind of start up on this side of the country back through the ’60s and ’70s, and the beer just came out of that. We’ve just gone balls to the wall with it since then,” said Jon Abernathy, author of Bend Beer: A History of Brewing in Central Oregon.

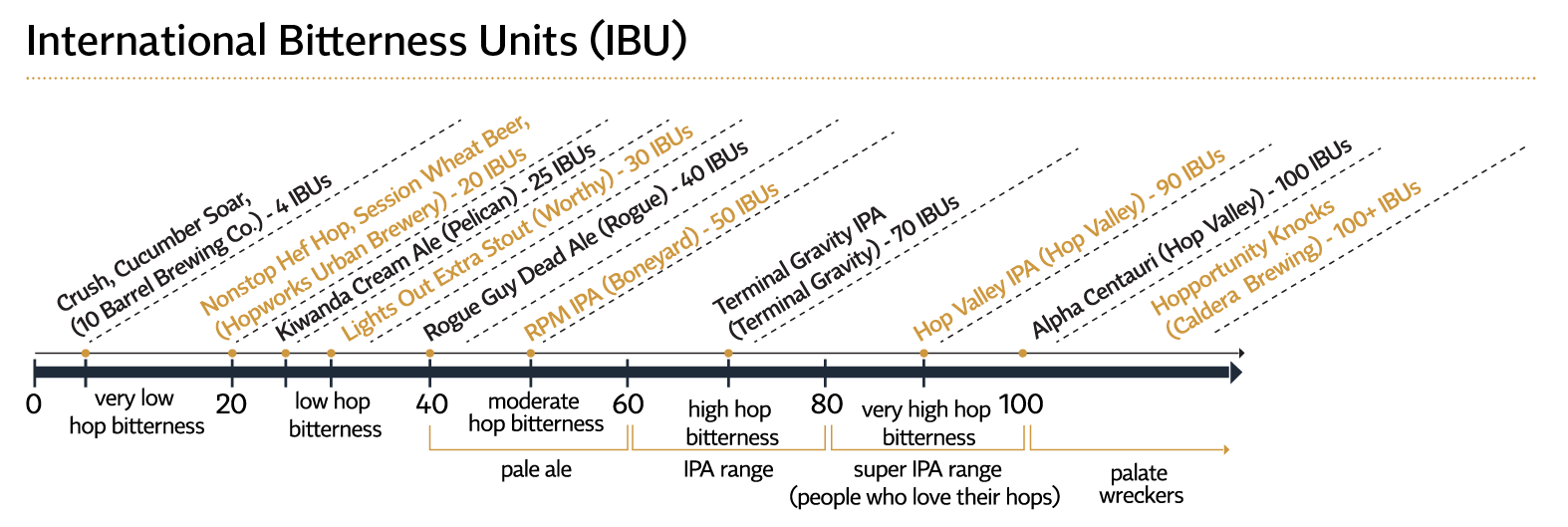

Oregonians love a little pine tree and grapefruit hoppy bitterness in their beer, which nods to the development of Cascade hops, the most widely used hops in the country. Turns out, Oregonians aren’t the only ones who like the taste of trees and fruit in their beer, because American IPAs (a.k.a., West Coast IPAs and Pacific Northwest IPAs) are taking over the world.

Oregon, as the resurgent state for great craft beer, harkens back with two Henrys. German-born Henry Saxer opened Liberty Brewery in Portland, seven years before Oregon’s statehood in 1859. Then the other German-American brewer, Henry Weinhard, took over and paved a path of hops and barley for the rest of us to follow. Weinhard’s Brewery, with its yellow, fizzy water, developed a bit of the contrarian and artisanal mindset that beer-drinking Oregonians still embrace.

“I’ve seen some of the folks in Portland consider Weinhard to be the first craft brewer, because of its private reserve when it came out, which was pretty much an all malt—very different formula than usual,” Abernathy said.

Another reason Oregon rules the beer world has something to do with its terroir. In fact, the United States is the largest hop producer second to Germany, and Oregon is the largest hop-producing state aside from Washington. The homogenized nature of our culture past the Second World War attempted to unify us. Americans, nonetheless, started asking questions of the status quo, which of course, eventually included beer. Perhaps it was this post-1960s gift of questioning authority combined with the relative remoteness of Portland from the rest of the country, but an independent DIY mindset that would eventually beget the mottos “Keep Portland Weird” and “Farm to Table.”

The Science Behind Beer

Beer doesn’t make itself. It’s a measure of science and art. In a nutshell, this is how beer is made.

Hops are harvested late summer. A portion of the hop cones go directly into boil kettles for the annual fresh hop beer production. A large portion of the cones are dried and stored for use throughout the year, while another portion is processed into pellets, oils and more. Meanwhile, maltsters are germinating their barley then drying and kilning it to various levels of color and flavor. Yeast is generally cultured and stored unless brewers, like The Ale Apothecary (Bend) and de Garde Brewing (Tillamook) either supplement or completely rely upon wild yeast in an open fermenter called a “coolship.”

First, the grain is milled or cracked open and set into hot water at a very specific temperature where enzymes will convert the starches in the grain into sugars creating a sweet tea called wort. After forty-five minutes to an hour, this wort is then recirculated in a process called “vorlauf” to help clarify the wort and compact the neutrally buoyant grain bed, which will then act as a filter. The clarified wort will then be drained off, or lautered, as more hot water is rinsed over the grains, or sparged, to extract the rest of the sugars.

The wort is brought to a rolling boil in the kettle where bittering hops are added. The resinous yellow beads in the hops require a rolling boil for

approximately sixty minutes to isomerize and create the bitterness a beer needs. Within ten to twenty minutes remaining in the boil, more hops are added for the aroma and the flavor. The hoppy wort is finally chilled rapidly and moved to a fermentation vessel where the yeast is pitched into the mix.

Ales are pitched with Saccharomyces cerevisiae and completely ferment in less than a week at relatively warm temperatures around 65 degrees. Lagers

are pitched with Saccharomyces pastorianus and continue to ferment for weeks in cool temperatures around 50 degrees. Each yeast strain has variations that result in different flavor profiles. Other beers, such as Belgian sours, add a few more characters to the party, such as Brettanomyces with its funky barnyard sour character, as well as Pediococcus and Lactobacillus who really get the sour juices flowing.

After the beers have fermented, brewers will clean up the beer either by filtration, centrifuging, using cold conditioning or coagulating compounds called finings. Now they carbonate the beer. Either brewers will add sugar or freshly fermenting wort to the batch to let the remaining yeast do the job, or they will pressurize it in a bright tank with carbon dioxide until it is ready to consume. The beer is now ready for cans, bottles, kegs and taps, while a little is lost to the angel’s share (i.e., evaporation).

When these four ingredients—water, malted barley, brewer’s yeast and hops—come together it’s like three chords and the truth, with their endless combinations to delight beer drinkers.

What We Talk About When We Talk About Beer

Lexicon of Beer

attenuation: consumption or removal of sugars by the yeast; brewers use a hydrometer to measure the gravity of the beer at any given time.

barley wine: the strongest of beers in terms of alcohol; typically start at ten percent ABV and go up from there.

barrel: wooden round containers that hold liquor; the measuring device for breweries. The U.S. beer barrel measures thirty-one gallons.

cask: barrel-shaped container made of wood or stainless steel that holds the precious “Real Ale.” A cask is tapped either with a spout or with a British beer engine (or hand pump). Beers from a cask are considered alive and a need special treat.

esters: flavor compounds that give beer a fruitiness, such as banana, pear, dried fruits and more; factors that affect ester production include fermentation temperature, yeast strain and even the design of the fermentation vessel.

flocculation: ability for yeast cells to clump together, thus clarifying the beer; yeast with poor flocculation tends to stay in solution and brewers then have to further clarify the beer or serve it cloudy.

off flavors: flavors in the beer that should not be there because they are, well, off. Examples include skunky or light struck beers that smell and taste of methyl mercaptan (think propane), stale flavors like musty and wet old wood, stale cheese from old hops, or oxidation, which has

the distinct flavor of licking cardboard. Some off flavors are acceptable in some beers at lower levels, such as dimethyl sulfide in lagers, which smells of sweet canned corn, or diacetyl, which smells, tastes and feels like popcorn butter or butterscotch.

phenols: flavors and aromas that usually indicate a problem; bad phenols include chemical taints and flavors of plastic or Band-Aids. Good phenols include vanilla from oak barrels, cloves in Bavarian Hefeweizens and smoke in Rauchbiers.

session ale: lighter alcohol beers generally less than five percent ABV; a perfect way to finish up an outdoor activity “session.”

standard Reference Method (SRM): a measurement of beer color; light lagers are approximately 2 to 4 SRM, light ambers are approximately 12 to 14 SRM and black stouts are 40+ SRM.

strong ale: catchall phrase for beers with a higher ABV; strong ale term used with European-style beers such as Duvel, a Belgian golden strong.

imperial ale: loosely describes a very strong ale; synonymous with doubles (as in double IPA). These beers have between 7.5 to 10 percent ABV.

nitro beers: beer carbonated with nitrogen instead of carbon dioxide; traditional and darker beers such as Guinness. Nitrogen gives a longer lasting, creamier head.

Ideal Beer Drinking Conditions

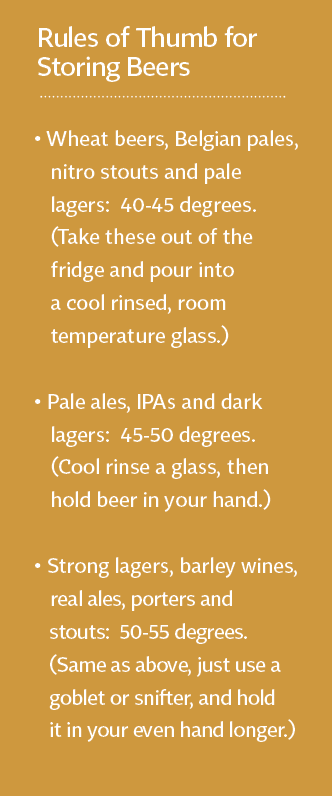

Let’s set the record straight: Americans have been lied to by Super Bowl commercials for decades. Ice cold beer does not taste better. The extreme cold actually suppresses the volatiles of the beer’s aroma, hence, suppressing the flavor itself. Ales and some dark lagers, when warmed up to a chilly room temperature typical of an autumn day in Oregon, will release the aromas and flavors and will unfold into something wonderful. Wine-loving Oregonians would look down their nose at people who put ice cubes in their pinot gris and pinot noir. Beer deserves the same respect and attention to temperature!

Things to Consider

- Think of ideal beer selection as a seasonal affective disorder—the hotter it gets, the lighter and more refreshing the beer should be.

- Let your palate be the guide.

- When the weather gets cold and Oregonians want to bundle and cuddle, bust out the darker and stronger winter warmer beer. Drink Imperial Stout, for example.

- No self-respecting, beer-loving Oregonian would put ice cubes in his beer, yet pubs everywhere do virtually the same thing by pouring craft beer into a frosted glass. “Foul!” would cry the beer referee.

Beer Glass Guide

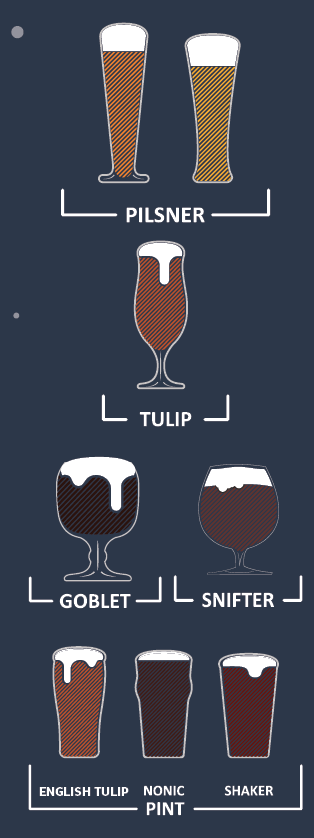

For lagers and pilsners try a tall and tapered pilsner glass. The narrow shape shows off the color and brilliant clarity while the taper supports the foamy head.

For most ales, a Tulip pint glass will do. Similar to a pint glass, but instead these have a portion that flares out to support the head, then tapers back down to concentrate the volatile aroma. Try a stemmed tulip for a fancier version.

For stronger and darker beers use a goblet or a snifter, which lends itself well to swirling and smelling as well as a bit of restraint.

Conical pint glasses found in nearly every brewery and every pub are also called shaker glasses because they were designed to fit into a larger metal shaker for cocktails. They were plentiful. They were cheap. It’s easy to print a logo onto these ubiquitous glasses. However, these are not particularly kind to aroma or flavor of the beer.

Beer Drinking 101

Welcome to Beer 101. Use this as your primer on how to drink a beer (there’s actually lots to remember, if you care).

Properly Store Beer

Everyday drinking beer will be kept in the fridge. Fridge temperatures, however, are too cold for all but light American lagers, and the beer needs to warm up just a bit to release its aroma and flavor. For exceptional, high gravity, high alcohol beers, cellaring is a really good option. These beers should be kept at a constant cool temperature. Unlike wine that is cellared on its side, beer should be kept upright so as not to rouse the yeast in the bottle, thus creating a cloudy beer. Therefore, try to keep these bottles as still as possible before pouring for the same reason.

Aroma

Aroma has a lot of stories to tell to the drinker willing to listen, which is why smelling one’s beer comes first. Smell beer early and often as it will continually change as the beer breathes and warms up. Notice, with a little practice, different aspects of malt and hops and a balance between the two, a perception of body and sweetness. A yeasty character may come through, and of course, there are the off aromas.

Pouring a Beer

To keep it simple, tilt the clean beer glass about forty-five degrees and slowly pour the beer toward the top of the glass, so it gently cascades down toward the bottom to avoid over foaming. Too aggressive and one may delay drinking. This is a great time to sniff the aroma and take note of what the beer smells like. When the beer is approximately two-thirds full, turn the glass upright and pour the beer right down the middle to create a good head.

Some beer styles like Bavarian hefeweizens add an extra step. These beers are characteristically cloudy and suspended yeast adds to the experience. For these beers, stop halfway through the pour to swirl the bottle, rouse the yeast and finish it off. Nitro beers tend to foam like an over-carbonated keg on a hot day. These take some time as the beer tender has to patiently “milk” the tap, remove some foam and milk the tap again until the glass is sufficiently full. The goal, depending on the beer, is to end up with a half- to-full-inch of foam on the top. A healthy head releases aroma and suggests a good experience. If the glass is clean and the head is persistent, it will leave behind a beautiful lacing pattern on the inside of the glass reminiscent of grandma’s hand-knitted shawl.

Appearance

Appearance is more than color, which is important. Is the beer cloudy when it should be clear or clear when it should be cloudy? What color is the head? How long does it last? What does the lacing pattern look like? Does the head consist of larger bubbles that resemble fish eyes, or is it a dense cappuccino type of foam? Keep in mind, few of these characteristics are deal killers, but they can be the difference between getting dressed up for a hot date versus throwing on the ratty old pair of cargo shorts from college.

Flavor

After taking a swig of beer, move the liquid all around the mouth to activate all the flavor receptors. Unlike wine drinkers who slurp and spit, beer drinkers need to swallow the beer to access the flavor receptors in the throat. Afterwards, exhale through the nose to once again get the aroma. Now play name that flavor.

Mouthfeel

What does the beer feel like in the mouth? If soft water and heavy whipping cream define the scale of body, decide where the beer falls on the scale. Does the carbonation prickle the mouth aggressively, or is it more restrained and creamy? Does the alcohol give a delightful warmth or is it boozy and spicy hot? Does the finish linger on and on, or is it dry and astringent like sucking on a dry tea bag? The reason for all these questions is to decide if the beer is appropriate for the style, and most importantly, is it enjoyable?

Overall Impression

After all the time spent with a beer getting to know it on a deeper level, picking apart each subtle nuance, it is now time to sit back and evaluate how it all went.

Beer + Food Pairing Guide

If you were to take a beer that “zings” and combine it with the right food that goes “boom,” the pairing creates a synergy that begets a “zing-boom-pow” effect. Enter food and beer pairings.

Classic pairings work because of the balance they achieve on your palate. Classic examples include the bitter hoppiness of an IPA balancing a slice of pepperoni pizza by complementing the fat and then cleansing it off the palate. The roasty notes of a porter or the boozy, alcohol warmth from a Russian Imperial Stout are calmed by the soothing touch of a bittersweet and rich chocolate soufflé (and vice versa).

Many brewers create their golden suds with the effect of taste and pairings in mind. Some beer cultures are so ingrained with this idea that they have taken to calling their creations gastro ales, or food-pairing beers.

Key Beer Sentiments

In Oregon, good food and good beer prevail. When you’re out and about with a drink menu and a meal menu, remember these key sentiments.

Complement, Contrast and Cleanse: Match similar flavors to complement such as a chocolate porter with chocolate. Pair opposites to contrast and create a balance such as a sour, acidic beer with sweet and creamy queen of cheese brie. Cleansing is using the carbonation and the character of the beer to wipe your palate clean such as a hoppy beer versus fatty food or a sweet malty beer versus acidic food. In the case of beer and brats, try a German-style doppelbock (“doppel” meaning double) and bratwurst for a great combo.

That Which Grows Together, Goes Together: There’s a reason why pineapple and coconut have combined so well to create a piña colada, because they grow next to each other. There is also a reason lime goes with Mexican food, wine goes with marinara and beer and brats work so well. Perhaps an elk burger with a marionberry and roasted hazelnut compote is the perfect pairing for a pine tree and grapefruit IPA.

Match Strength with Strength: A delicate lager will get lost in a beef stew. A British barley wine will dominate a summer salad. Match the strength of flavors, alcohol, body, acidity with the food for an easy zing-boom-pow pairing.

Experiment and Have Fun: The best way to figure out beer pairings is to talk to brewers and chefs about it and try different things. Create a food and beer tasting party for guests where one pairs several different beers side by side with several different food items. Imagine creating your own Thunderdome-style cage match where guests pit their beers against each other and everyone votes on the best pairing. “Two beers enter . . . One beer leaves!”