Rodeo clowns are actors performing dangerous improvisational theater before live audiences. Wearing multicolored masks layered in gaudy grease paint, they symbolize ancient Greek muses. Protecting and liberating the rider from calamity is the job of Melpomene, the scowling face of Tragedy. Meanwhile Thalia, the smiley face of Comedy, is busy court-jesting and regaling children with tomfoolery. How well the theatrical performance is received depends, in large part, on the chemistry between these two opposing forces—Tragedy and Comedy.

Folks, take a gander over at chute number three. Snortin’ and tossin’ about is ol’ Volcano, one of the meanest Brahman bulls you’ll ever lay eyes on here at the Molalla Buckaroo. He’s tossed off ninety percent of the cowboys that’ve straddled his back, but he is ridable. Here to prove it is three-time world bull riding champion, Johnny Ray Langan from Sumpter, Oregon. Oh what a match-up we’ve got today folks … and all right here in the great state of Oregon … home to some of America’s finest rodeos! ~ Rodeo Announcer

George Doak was born in 1937 and raised in Ft. Worth, Texas. He began his professional clowning career in 1953, clowned the major rodeos in the Pacific Northwest and became a legend on the wrong side of the bull.

“Oregon was such a great place,” says Doak. “What I enjoyed most about rodeoin’ up there was the people. There were so many good cowboys. Joseph was one of my favorite rodeos. I went to Chief Joseph Days, and that was like being in the Swiss Alps!”

The story of how rodeo came about in these parts can be traced back to the waning years of the nineteenth century when cowpokes from adjoining outfits would gather informally to challenge each other’s riding and roping skills. As barbed wire and homesteaders began partitioning the open range, and railcar travel began replacing long distance cattle drives, the transient cowboy lifestyle became more confined. Under these constraints, cowboys created the rodeo, which, some historians argue, is the only American sport to be born out of industry.

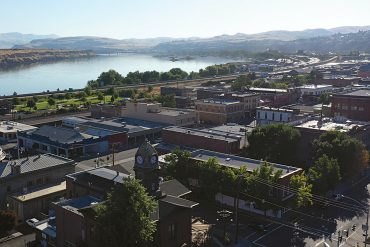

In Oregon, the conversation begins in Pendleton. Inaugurated in 1910, the Pendleton Round-Up now draws more than 40,000 spectators and nearly 700 contestants each year, making it not only the biggest rodeo in the state but one of the largest and most prestigious in the country.

After nearly two decades clowning at the Pendleton Round-Up, Doak hung up his breakaway britches for the last time in 1981. In his heyday, he clowned at thirty-five to forty rodeos every year and says he would do it all over the same way again.

“My folks thought cowboys were heathens,” says Doak. “When a rodeo came to town, you put your wives and kids up. How I got started rodeoin’ was really by accident. I was still in high school. One of the riders got hung up, and I run out there and got him loose. The producer came up and asked if I wanted to bullfight for the next few events, and he paid my entry fees. I thought, ‘Well, that seems like a good deal.’

“I quit college. I was raised to be a mechanical engineer, but I didn’t want to do that all my life. I was young and stupid. People said, ‘Why did you start rodeoin’, and I said, ‘I was already getting stupid, I guess.’”

From 1953 to 1981, Doak put his life at risk as a bullfighter to save bull riders. One bittersweet chapter involved a hostile bull they called Little Mexico.

“The bull rider, John Davis, had him drawed and they went into a spin,” recalls Doak. “I got up on his head. Instead of throwing me up— being a Mexican bull—he didn’t buck up. As soon as he dropped me, he hit me and broke my nose. I got up and got to the chute. The rodeo producer was there and he asked me, ‘George, are you all right?’ I said, ‘Yeah. Being from Texas, I remember the Alamo.’”

One of the great American fiction writers of the twentieth century, Ernest Hemingway, wrote about a code of conduct he called, ‘grace under pressure.’ These were critical moments in the narrative when characters, matadors for example, were threatened with death. Their ability to handle this intense pressure defined their grit.

“People ask me if I was ever scared, and I said, “No. I just stayed that way instead of gettin’ that way,” laughs Doak. “There were always some really bad bulls, and I sort of dreaded them when they showed up.”

While clowns of yesteryear not only were the de facto bull target, they also had to win over fans with costumes, cosmetics and comedy. Today, clowns have refined their jobs as bullfighters in makeup.

“Back in our days, when we first started, I used to adlib,” Doak recalls.“If something was taking a little time, you just walk out in the arena and holler at the announcer and get something going. Any time you’d get a laugh from a kid or his parents, you knew you were doin’ all right.

“I had a trained rubber chicken. People would say, ‘What does a trained rubber chicken do?’ I says, ‘Nothin. But I’ll always have ‘em, and he won’t come untrained because he doesn’t do anything to begin with.’ I’d shoot him or I’d light him on fire and put him down my britches. A burnin’ chicken down your britches—what kid doesn’t like that?”

RODEO ANNOUNCER: Wait a minute; hold on to yer hats folks, Johnny Ray is having some trouble lashing up to ol’ Volcano. Oh what’s that you say, George? George Doak, ladies and gentlemen, our high-spirited clown down here in the arena.

RODEO CLOWN: Did you hear about the Idaho potater who met an Irish tater and they married?

RODEO ANNOUNCER: No George, I have not heard nothin’ bout that couple.

RODEO CLOWN: Well, soon they had a sweet little tater and she said, “I’ve got a thing for Paul Harvey and want to marry him.” Her daddy grew angry and said, “You can’t do that.” She said, “But why? I love him!” The daddy said, “Why? Cause he’s just a common tater.” (On cue, the crowd moans.)

“What kind of blood runs through the veins of a rodeo clown? I’m not real sure ‘cause they’re so different,” says Wayne Brooks, twotime Professional Rodeo Announcer of the Year and current voice of the Pendleton Round-Up. “And I mean that as a compliment.”

This bravado plays out on both sides of the horns of monstrous Brahman bulls. Make no mistake, bull riding is rodeo’s most dramatic and dangerous event. It’s also the most popular due to its high degree of uncertainty—whether a rider lives or dies, for example. “Rodeo is a primal man against beast situation,” Brooks acknowledges. “It’s very simple to understand. If you can ride a bad bucking horse or a mean bull for eight seconds, you can win.”

The relationship between bull rider and clown is that of patient and heart surgeon—one built upon complete trust. Four-time Bull Riding National Finalist and Oregon native, Dustin Elliott, characterizes the weight of the bond this way, “We’re trusting our lives in their hands and a lot of times, I don’t know the bullfighters personally, yet I know that every time I nod my head they’re gonna give it 110 percent to be able to save me if I need it.”

In his novel, Last Go Round, Oregon’s most prolific novelist, Ken Kesey, drilled deeper into this culture. “The crowd likes to be led to the yawning brink of danger, then, after gazing down into it long enough to feel a good shiver, to be led safely back away from it. This is the rodeo clown’s real job. After he drags some peachy-cheeked boy out from under a thundering ton of orneriness, the clown has to turn around and dance in that thunderstorm’s face. Kick dirt, spit, fart at the beast—anything offbeat enough to turn fear into fun, to mock the monster.”

This action begins when the steely-eyed cowboy lowers himself into the chute, bestrides the bull’s back, loops his flat braided rope around the bull’s girth and then tightly wraps the remainder around his open palm. After punching his now clenched fist a few times to ensure that he is securely tethered to the brute, he pulls down the brim of his Resistol. The gate opens, and the drama begins.

“I think being a little scared is part of the thrill of it,” says Elliott, whose already won two bull riding events this season. “That’s how your adrenaline gets up so much, because there is that danger part of it.”

It’s been said that all a rodeo cowboy really needs is a tank full of gas and rodeo entry fees. Maybe so, but getting to the podium is a long, tough hardscrabble climb, as Elliot figured out on his way to claiming the 2004 Bull Riding World Championship. “You’re not going to ride every bull you get on,” he says. “You will get bucked off. That is one hundred percent guaranteed true, and to be completely honest, if you ride sixty percent of ‘em, you’re doing really well. So you have to learn how to lose.”

OK, I reckon he’s ready. Here he comes, Johnny Ray Langan, aboard two thousand pounds of calloused contortions! Help him out folks, he’s going to need it. Wow, look at him go! That ol’ Volcano’s a kickin’. That’s a belly roll … Whoa, now he’s doin’ the sunfish … That there bull’s an ornery one all right. Johnny Ray looks like he’s gonna make it though … He’s almost there. He’s got it … eight seconds … and the whistle! Oh my gosh, I can’t believe it! This bull has been nearly unridable for two years and now he’s been outlasted.

Wait, he’s hung up, Johnny Ray can’t seem to get his gloved hand free to dismount … here comes George … he’s runnin’ in close tryin’ not to get hooked … he’s reaching up for the rope … He’s got it! … The rider’s off! A close call, yessiree!

Hold on, the judges are talking it over, the scores are in … An unbelievable 93 points! What a ride, what a bull, what a save! ~ Rodeo Announcer

The lore surrounding the “Let ‘er Buck” Pendleton Round-Up keeps Elliott coming back every year. “It’s the one that everyone wants to win just because of the tradition,” he says. “I mean, they still have the old bucking chutes from back before I can even remember what bull riding was. And they still rodeo on grass.”

Before Elliot ever straddled a bull, touring riders revered Doak for his plucky approach to his craft. Smart, agile and athletic, he had a knack for knowing when to get in and when to get out of harm’s way. Tenacity was his trademark.

So too was his remarkable ability to turn a bull’s attention away from a thrown rider and onto himself.

“The rider finishes the ride, and you got to distract the bull so the rider can get off and don’t get hung up or hooked,” says Doak. “Normally a bull will pick you up and throw you out of the way, so you got to know which way they hook so you can get by ‘em pretty easy. An ol’ smart bull would walk up to you and hook the hound outta you. They’re just as scared and nervous as we are.”

When George Doak exited the arena for the last time in 1981, it was a tremendous loss for the sport. After thirty years of iconic contributions, as both masterful showman and all-around good guy, Doak was inducted into the Pendleton Round-Up Hall of Fame, the Pro Rodeo Hall of Fame and three other halls of fame. The Pendleton Round-Up, turns out, would be his final curtain call.

“You just got to make up your mind when to quit,” says Doak, now 75. “It’s just like any bad habit, like smokin’, you just gotta say, ‘I quit.’

“I was awfully lucky. I’ve had a very blessed life rodeoin’. I’d probably do it all again the same way because I loved it so much. You know, you can’t express it, you gotta live it.”

First Clown Reunion

Retired rodeo clowns are a fraternal bunch. Every year or two they get together in grease paint and garb to honor old friends and to skylark with adoring fans. This has been a tradition since 1974, when at the Umpqua Valley Roundup in Roseburg, Hall of Fame rodeo clown Karl Doering rustled up about twenty of his brethren, including George Doak, and inaugurated what has come to be known as the ‘The Rodeo Clown Reunion.’ This summer, you can find these funnymen waggishly delighting audiences July 11 to 14 at the Sheridan WYO Rodeo in Wyoming.

Big Bucks

Winning is everything. Last year the Professional Rodeo Cowboys Association (the sport’s sanctioning body) paid out nearly $39 million in prize money. Comprising roughly 7,000 competitors and 575 rodeos in forty states (and four Canadian provinces), the PRCA is the undisputed leader in professional rodeo.

One of twelve regionally sponsored PRCA circuits, the Columbia River Tour serves the Pacific Northwest. Fourteen of the tour’s twenty-seven events, including the Crooked River Roundup, Chief Joseph Days Rodeo and the Elgin Stampede, are staged in Oregon. Many local cowboys, such as four-time World Bareback Champ, Bobby Mote of Culver, Shawn Greenfield from Lakeview, Jason Havens of Prineville, Steven Peebles of Redmond, Allen Helmuth from Eugene, Trevor Knowles of Lake Vernon, Brian Bain from Culver, and Brandon Beers from Powell Butte, have ridden, roped and wrestled their way to stardom via this esteemed circuit.

Even though bucket loads of other small towns like Burns, Sweet Home, Tillamook, Vale, LaPine, Yoncalla, Spray, Heppner, Sublimity and Halfway are not on the Columbia River Circuit, they host their own brand of down-home professional rodeo events each summer.

So glad you posted this as a retired clown myself I love reading about the ones that brought the sport to where it is today!