written by Eliza E. Canty-Jones

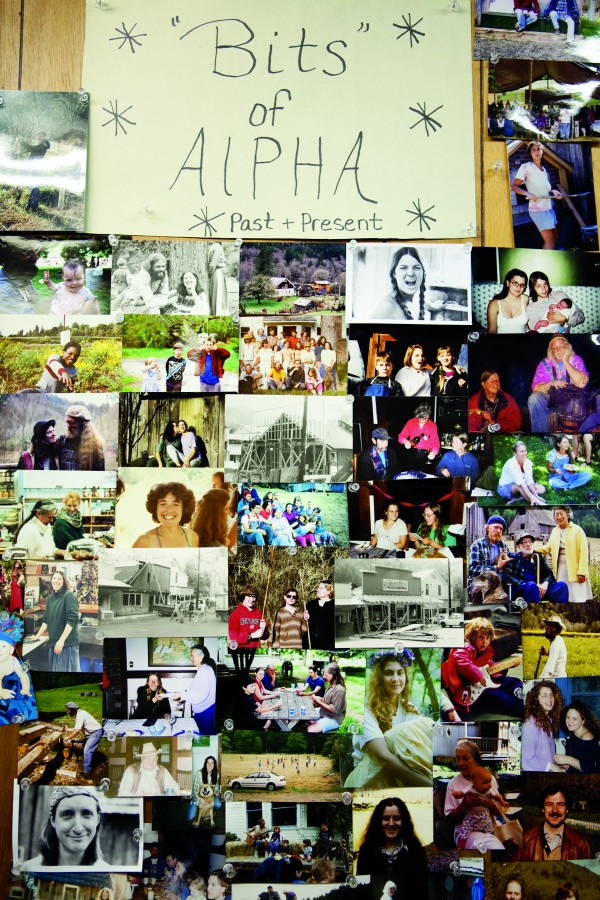

Deep within the Coast Range fourteen miles east of Florence, Oregon, a dozen or so members and residents of Alpha Farm have their days scheduled on a hand-drawn chart hung on a kitchen wall.

They tend to a large garden and orchard, care for children and chickens, prepare evening meals for one another, keep the farmhouse clean, haul firewood, fill woodstoves and work shifts on a mail-delivery route or at their café and shop, Alpha Bit, in nearby Mapleton. Most have come to this commune within the past three years seeking alternative lifestyles. One resident characterized the place as a “community boot camp.”

According to a booklet outlining Alpha’s history, optimistic young Quakers from Pennsylvania founded the commune in 1972 because they “saw the Northwest as being generally open-minded and tolerant,” not to mention “the climate was mild, educational facilities were good, the ocean was nearby, and the land seemed not particularly prone to earthquakes.” Two of those founders still live along Alpha Creek, in the “new house,” where members gather for meetings and make decisions about how to continue living as a group of equals seeking “to change the world, not by proselytizing or politicizing, but rather by allowing a fullness of spirit and openness of heart to be dominant in us.”

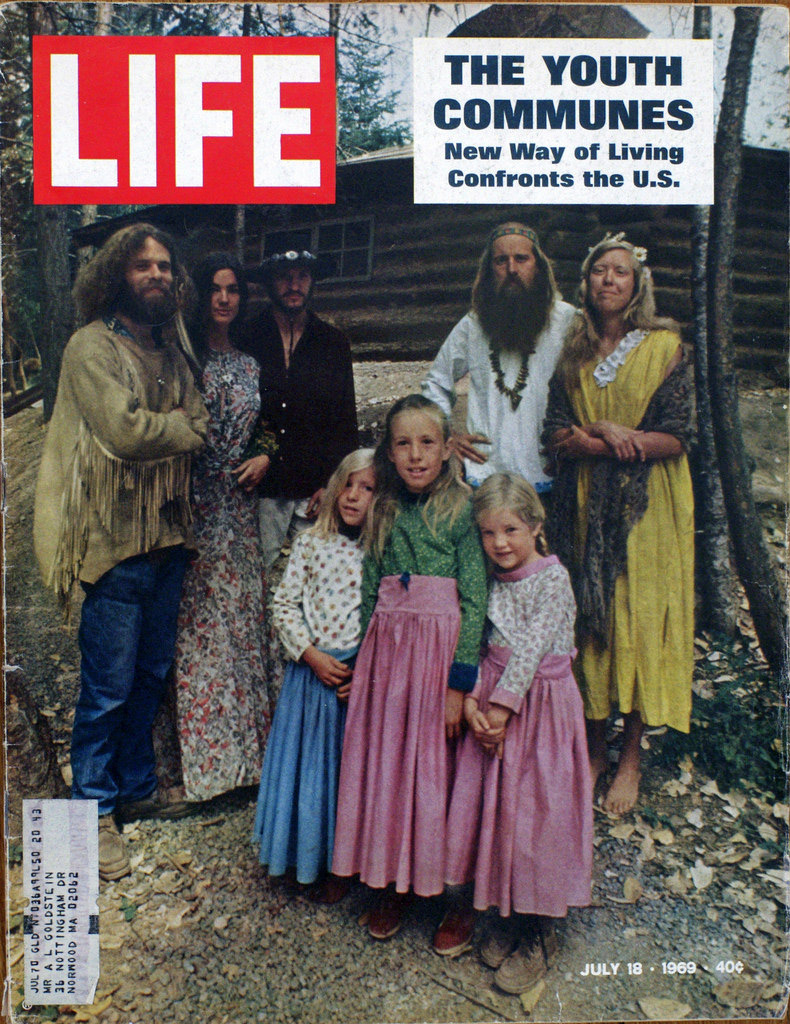

Alpha Farm was founded just three years after Oregon’s Family of Mystic Arts Commune was featured on the July 18, 1969 cover of LIFE magazine, that introduced a new wave of communalists with radical lifestyles.

Communes are just one part of the larger hippie movement whose influence in Oregon culture and history is evident today. Hippies were a driving force behind farmers markets, organic foods and weekly and seasonal craft and music fairs. They preached the environmental awareness, sustainable land use, renewable energy, and transportation policies that help define the state today.

In the 1960s and 1970s, hippies found a special home in Oregon’s rural areas, where they founded dozens of communities like Alpha Farm, and in cities, particularly in the Willamette Valley, where businesses and programs that were once considered radical and marginal now thrive and are even mainstream today. From recycling to acid tests, from Ken Kesey to organic food, and from pacifism to local DIY fervor, Oregon’s character is the love child of the marijuana-smoking long-hairs who fostered Oregon’s back-to-the-land tradition.

Just decades after non-Native explorers and fur trappers began infiltrating the Oregon Country in the early 1800s, tens of thousands of emigrants traveled west from Missouri in long, arduous wagon trains. The trail split at one point, going north to farmland in Oregon and south to goldfields in California. According to legend, a depiction of a pile of gold sat under the arrow pointing south, and Oregon was written on the one pointing north. Those who could read went to Oregon. Aside from the insult to Californians, the old tale identifies Oregonians as intellectual people who seek personal fulfillment before material wealth. Many of those pioneers sought the freedom to create their own self-sustained society, and Oregon had the climate and landscape to support their dreams.

Almost a century later, after the homesteads had long been claimed, cities were well established, and resource-extraction industries had taken hold of the region’s economy, pacifists who refused military service during World War II created an art school within their Civilian Public Service work camp along the coast between Waldport and Yachats. Explore the locations of the camps here. They dreamed “vaguely of sticking together after the war,” according to book-printer Adrian Wilson. “What a community center I visualize,” he wrote home to his parents. “We would earn money from the press and more from crafts—myrtle-wood, etc.” When the war ended and they were freed from the camp, Wilson and several other artists settled in San Francisco, where they helped build a community of artistic resistance to mainstream culture that would support the radical writers who came to symbolize the Beat generation.

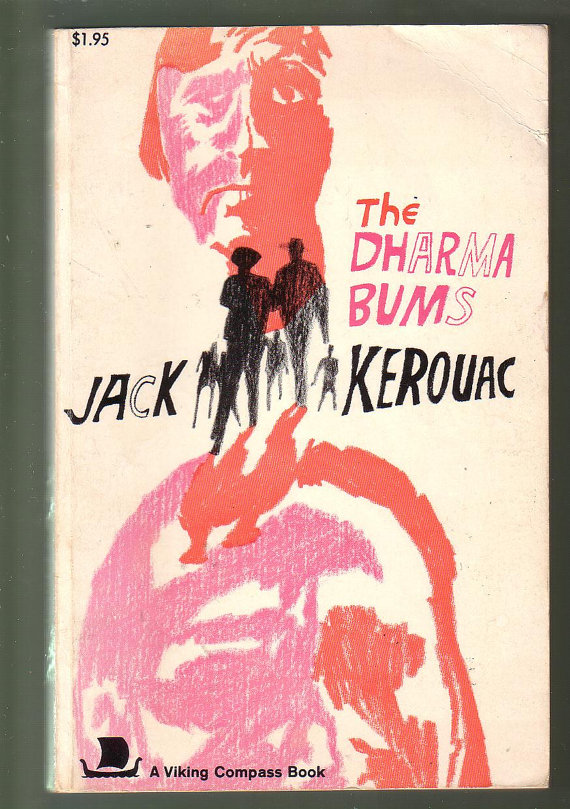

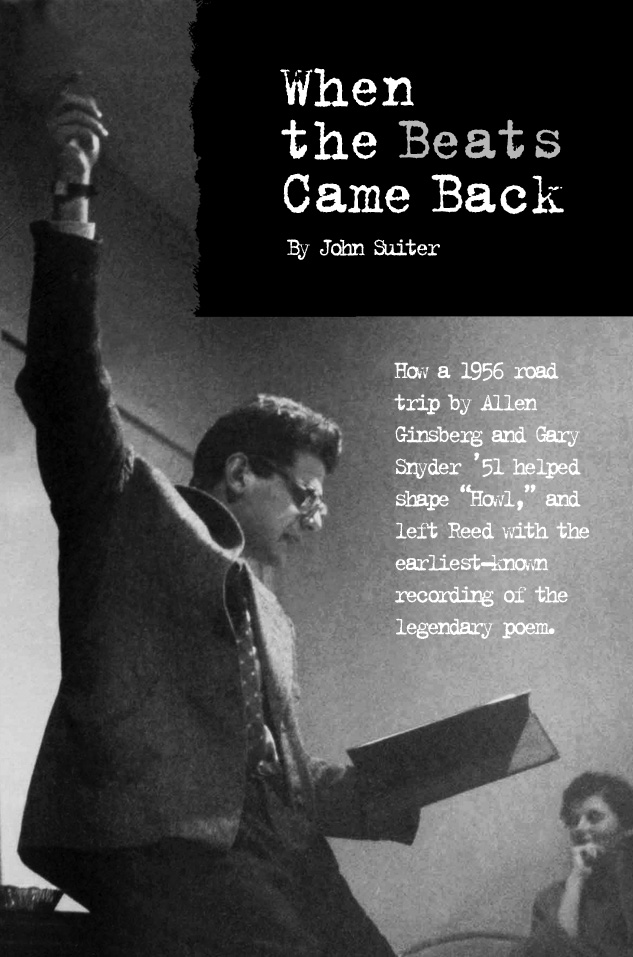

Like the hippies of later decades, the Beats railed against the “straight” elements of society. With the opening line to his poem “Howl,” Allen Ginsberg cut against the national post-war narrative of affluence and security. He wrote, “I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness.” In his 1958 novel The Dharma Bums, Jack Kerouac included a thinly-disguised description of ”Howl’s” October 1955 reading at San Francisco’s Six Gallery, where listeners (including Kerouac, who had taken up a collection to purchase jugs of cheap wine) wildly applauded the reading. “By eleven o’clock when AlvahGoldbook was … wailing his poem ‘Wail’ drunk with arms outspread everybody was yelling ‘Go! Go! Go!’ (like a jam session).” Just a few months after that first performance, Ginsberg joined fellow radical poet Gary Snyder for a reading at Snyder’s alma mater, Reed College in Portland. Click here to listen to a recording of the performance, the earliest recording of Howl in existence.

The Music Scene, Coffeehouses and the Birth of the Oregon Country Fair

These writers and poets found a home in coffee shops, where folk singers also played to audiences and where the next wave of counterculturalists would soon follow. Walter Cole bought Caffe Espresso in Portland in 1957 and quickly started booking musicians to draw in more customers. His house musician, Earl Benson, played in the jug band Fourth Gear Rubber, which “made a bridge between the solo folksinger and the electric rock band,” according to Valeria Brown, a historian of the era. Within a decade, Bob Dylan had plugged in at Newport and 15-year-old Steve Bradley had formed Portland’s U.S. Cadenza, a rock band that opened for the Grateful Dead at Portland’s Masonic Lodge on July 18, 1967. Brown explains that young musicians like Bradley, influenced by jazz and the blues, spent many hours in Portland coffeehouses, “improvising accompaniments to each other’s material.” Such willingness to experiment was a defining feature of the era.

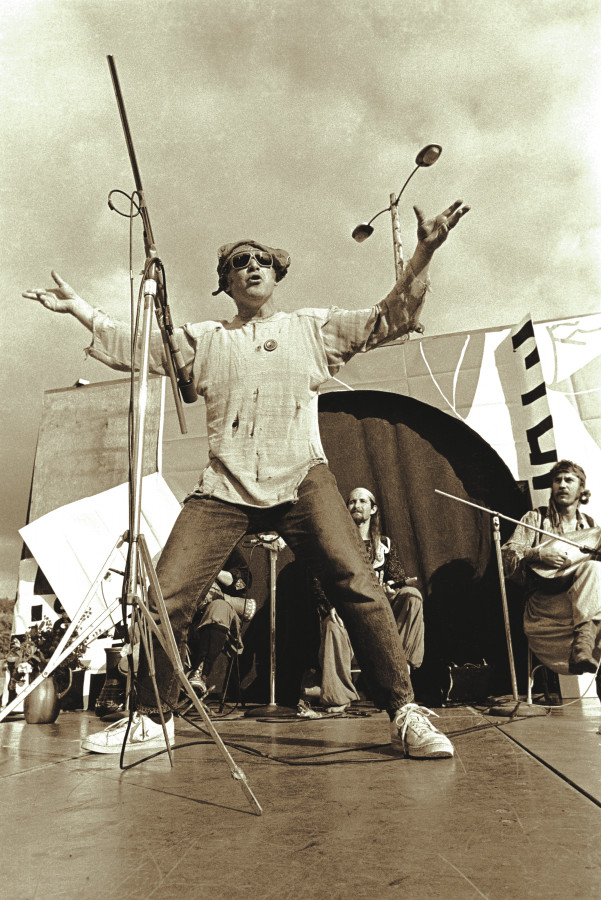

In the recently published book, Fruit of the Sixties, Suzi Prozanski documents the people and ideas that created the Oregon Country Fair, an annual three-day festival “where aging hipsters, sacred tricksters and new vaudevillians, plus their children and grandchildren, would gather for decades to celebrate counterculture community.” She includes a full chapter on the Odyssey Coffee House, which opened in Eugene in October 1967 and “quickly became a meeting place for people exploring new ways of living and working together,” or as co-founder Bill Wooten put it, a place for “activists, university students, high school dropouts, hippies, street people, musicians, artists, bohemians, beatniks, and bums.” During the five years the shop was open, owners and patrons used the space to plan anti-war demonstrations, sell crafts, plan the renaissance fair that would become the Oregon Country Fair, create a “switchboard” through which members of the alternative community shared information, and plan a community free school that taught courses ranging from yoga, existentialism, and batik to women’s liberation and African American studies. Such courses are now common in universities, and crafters who met at Odyssey later started the Eugene and Portland Saturday markets, now cornerstones of local food and craft economies.

Not all Eugene citizens were pleased to have such a colorful counterculture in their city. During a three-hour panel discussion and forum on the Free School in July 1969, some people “shouted hysterical accusations that the school was run by left-wing revolutionaries, atheists, drug addicts and sexual perverts.” An Odyssey regular, Mary Wagner, resists such characterizations, explaining that “so frequently, the hippie counterculture that’s portrayed today is just a big drug indulgence,” when in actuality, “the Odyssey was like a center for thought and intellectual stimulation and music and art.”

The Kesey Trip

Of course, drugs did play a starring role in the culture revolution. A self-described “old hippie” now living at Alpha Farm recently justified his commitment to a life far outside the norm with a question: “Have you ever tried LSD?”

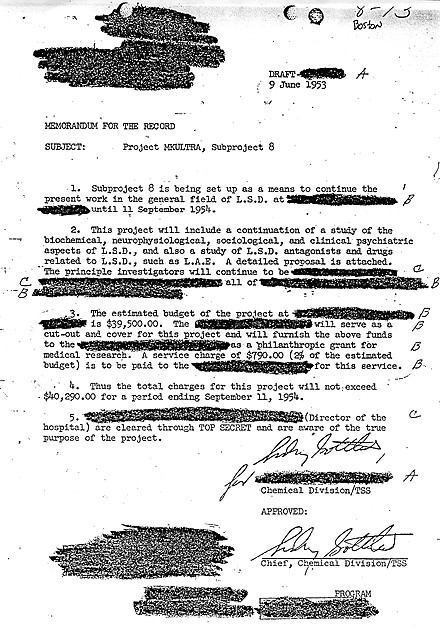

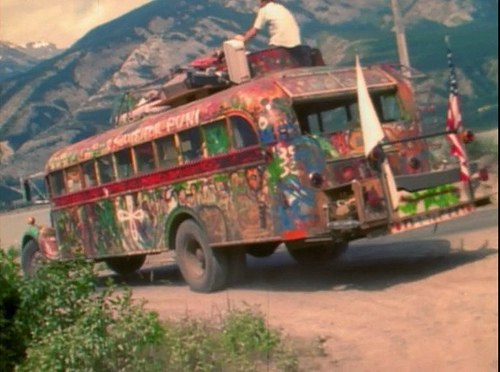

Working to understand the potential military applications for psychedelics, the CIA experimentally administered LSD (or acid) to people under a program called MK-ULTRA. Oregonian Ken Kesey became a test subject in the mid 1960s, while living outside San Francisco. Kesey then liberated some of the LSD and began using it outside the program. He promoted LSD’s visionary effects in a 1964 crosscountry tour with the Merry Pranksters on their brightly painted bus called “Furthur.” Writer Tom Wolfe made that trip famous in his 1968 book The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, where he also described the “acid test” parties Kesey and the Pranksters hosted while the Grateful Dead supplied music. All these parties took place in California except one.

Kesey, the Merry Pranksters, and the Dead journeyed north to Portland’s Beaver Hall in January 1966. Kesey later told this story about the show: “A guy off the street, a businessman, came in and paid his dollar and got his hit of acid. He had a suit on and an umbrella. At that time, [each acid test] was still small enough that one person could become the center of attention. He was out there dancing and somebody hit him with the spotlight and he said, ‘The king walks!’ And he began to walk with his umbrella and play with his shadow.” Calling attention to the symbiotic relationship that fans of jam-band music continue to revel in today, Kesey went on: “The Dead were watching this and playing to every moment so he became the music that people were playing to.”

Hunter S. Thompson wrote that, in the mid-1960s, “anything was possible. The crazies were seizing the reins, craziness hummed in the air, and the heavyweight king of the crazies was a rustic boy from Honda named Ken Kesey.” Leader of the acid tests and the Merry Pranksters, there is no doubt Kesey’s early days established his hippie bona fides, but his later years reflect the maturity of the movement in general. He continued to take LSD, at least once a year, almost until the end, and he also farmed, wrote, edited, served on the local school board, coached wrestling, practiced magic tricks, worked on creating a movie from film of the 1964 Furthur trip and taught at the University of Oregon. That mix of individual expression and community building is a potent residual of the hippie era, one far easier for many to appreciate than patchouli.

Perhaps the grandest ruse in hippie lore anywhere, came under the seal of the State of Oregon. Oregon hippies helped organize a state-sponsored, drug-filled, rock-and-roll festival. The impetus for the concert was based upon the political activity that placed them front and center on the six o’clock news— protesting the war in Vietnam. Held from August 28 to September 3, 1970, just a year after Woodstock, the festival, Vortex I, was the brainchild of a few hippies who persuaded Governor Tom McCall to accept a quid pro quo. Earlier that year, massive anti-war protests had filled Portland’s South Park Blocks, and the Ohio National Guard had fired on protesting students at Kent Sate University, killing four. With the FBI raising the alarm that unruly hippies would descend on Portland to cause mayhem during an American Legion convention with headliner Richard Nixon, McCall took a much-ridiculed chance. Police directed 35,000 hippies to a muddy, LSD-infused party at McIver State Park, forty-five minutes southeast of Portland. Nixon decided not to come, and although the People’s Army Jamboree organized a healthy anti-war protest, McCall never called out the National Guard troops stationed downtown.

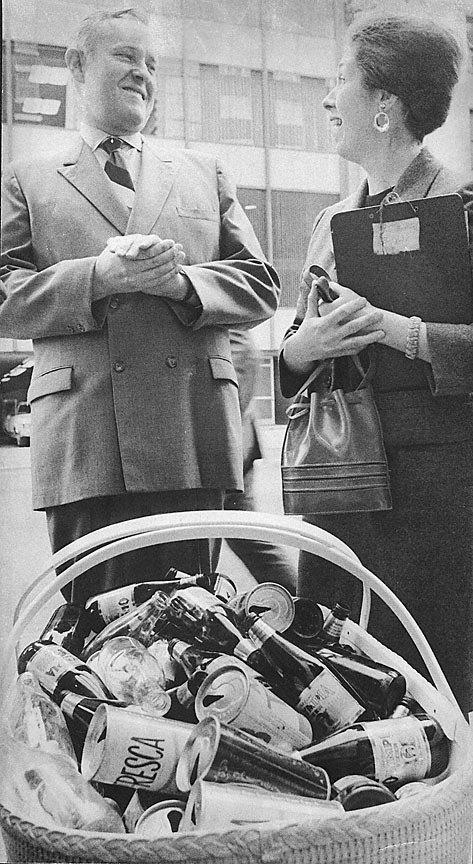

Along the Clackamas River at McIver State Park, however, hippies turned out in droves and the concert was widely hailed as a success. Two months later, McCall was re-elected with 56 percent of the vote. In that second term, he signed two pieces of legislation that defined Oregon as an environmental leader—the Bottle Bill, which encourages recycling, and SB 100, Oregon’s trademark land-use policy. Vortex may not have been the sole cause of that legislation, but its success and the radicals’ overall stretching of the political spectrum undoubtedly contributed to its existence.

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., cn012697

Americans coming of age during the mid-20th century found good reason to rebel against the status quo. The Vietnam War’s ongoing carnage, police brutality at antiwar and civil rights protests, the continuing draft, the threat of nuclear war —heightened during the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis—and the publication of Rachel Carson’s environmental opus, Silent Spring, all sent a clear message about the future. Young people were “shell shocked,” as 1970s Portland commune member Lee Lancaster put it, especially after the assassinations of John F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King, Jr. Nevertheless, the mostly educated, white hippies mixed that shock with youthful optimism and set out to make a safer, more colorful, more peaceful world than the one their parents had built.

Identifying as a hippie, Lancaster says, was “a hell of a lot of fun, because that’s what we did to express ourselves.” Through wearing tie-dyed shirts, bell-bottom jeans and flashing the ubiquitous peace sign, hippies were instantly recognizable. It was all “an expression of throwing over the ’50s suburban values, enjoying life every day and not worrying too much about the future.” Lancaster and his fellow communalists didn’t just rebel through drugs and clothing, they also took action—protesting the building of the Trojan Nuclear Plant in Rainier, Oregon, establishing the first household recycling pick-up program in Portland, and helping create markets for organic foods.

Lancaster now works as the finance manager at a local co-op, where he has worked for many years. He enjoys sharing his perspective and experience with a younger generation who he says is more cynical but has deeper understandings of problems and solutions than he and his cohorts did forty years ago. Just a few decades ago, he notes, scientific recognition of whole ecological systems was brand new, and the word sustainability was virtually unheard. The counterculturalist commitment to cooperative business and living models, healthy foods, and sustainable agriculture and energy use set them apart forty years ago, but those values are now mainstream in urban and rural communities all over Oregon.

Hippies Today

For better or for worse, the hippie haze, complete with hemp bracelets and “for tobacco use only” glass pipes, continues to find new generations of customers in head shops all over the state. But defining hippies today is a challenge. Are the only true hippies those who embraced prose, pot and protest in the 1970s? Or is the hippie ethic something that pervades various sectors of Oregon society—from young people who continue to flock to Grateful Dead cover-band shows to today’s commune residents and those who work in ecological sciences, environmental politics, or sustainability movements of one sort or another? The State apparatus has never sponsored another rock festival such as the Vortex, but bluegrass, jam-band, and newer electronic ensembles draw crowds of colorfully clad, happily tripping fans to shows and festivals. And, of course, the Oregon Country Fair is a well-established event that draws crowds year after year.

The freedom-loving counterculturalists have built systems through which they maximize their otherworldly fun, perfecting their costumemaking and stilt-walking as well as building colossal floats for annual festivals like Nevada’s Burning Man. Even drug use is more institutionalized, with medical marijuana almost a non-issue in Oregon and the possibility of decriminalization altogether in California, where the argument for regulation and taxation may hold sway with a bankrupt state government.

Some enduring aspects of hippie culture have become Oregon’s strong suit today. Oregon ranks among the top states for its recycling programs. State government incentives for green energy are among the most aggressive in the country. What Detroit was to automobile manufacturing, Portland and Eugene are to the bicycle. And Portland State University now has a conflict resolution program, contributing to the long-term advocacy of peace. Robert Gould, chair of the department, was involved in anti-draft organizations in Portland during the late 1960s and 1970s and remembers both hippies and “New Leftists” being involved in the peace movement then. “People like myself worked both sides of the street,” he recalls, having both founded a head shop, Ides of March, whose products “filled out the hippie lifestyle” and worked with Oregon’s U.S. Congresswoman Elizabeth Furse to found the Oregon Peace Institute in the 1980s. When describing the counterculture’s influence on the peace movement in Oregon, Gould emphasizes the work of women, “who have constantly been a presence in the peace movement,” and the effect of psychedelics, which “allowed for a consciousness shift that prompted empathy” by making it “possible to think about what it was like to be a person in another culture.”

While some hippie-era cooperatives have failed, many continue to turn a profit in Oregon, offering workers, owners and customers the means to put their values to work through business. Hippies of decades gone by are leaders in these institutions and more. They support community agriculture programs (and are sometimes the farmers) and are board members helping to govern local co-ops, businesses owners of clean energy companies, scientists studying ecological systems, and politicians working within the system for environmental regulations and social justice.

https://1859oregonmagazine.com/explore-oregon/trip-planner/oregon-trip-planner-lighthouses/

Isaac, if you would like to hear something different about Ken at the end, and about the Eugene hippie founded, ever-since cutting-edge organic produce company, and the history of the 100% consensus-run Mountain Grove Community founded in 1969 by a disciple of J.Krisnamurti, on land near Glendale, OR —- and all from a perspective both passionately supportive and critical, give me a try.

it was a big house in cornelius near beaverton and there was david hunger,doug barnet,ron carlton,jim lyons,and more i don’t recall the names but it was a good time,they’d called me lamarde for fun sometimes cause of my frenchcanadian culture,if any of you guys stil alive…..i’d love to hear from ya’s…

What an incredible article. Thank you. I lived in a commune known as The Dillard Road commune. We had 16 people including a Rock and Roll band. I was also ‘On the Bus’ beginning on July 8th, 1969. As a 6th generation Oregonian, I can tell you the ethics of us ‘Flower Children’ (between the Beats and the Hippies) were very much like those of my Pioneer Ancestors. Flower Children were not so much about pot, sex, drugs as we were about Music, Community, Environment and Theater. The ARTS.

I was a delegate to “Bend in the River”, the conference organized by Kesey to discuss the future directions Oregon should go. He traveled around the state collecting delegates from the alternative communities in each part of the state to attend a hour long statewide gathering in Bend that would be broadcast by radio in all the cities that the delegates came from.

I was one of the three delegates from Astoria to attend. It was well organized however the radio program was delayed by 10 minutes as one of the delegates, when stressed made toast, unfortunately her toaster brought down the electrics in the whole auditorium in Bend. Otherwise it went of well.

I spent time at Kesey Ranch afterwards writing the communications section of the published report.

Bend in the River was significant in coalescing the alternative communities at the time.

That man is not called Jokerman. His name is Frog. Ask anyone in Eugene, OR. His name is Frog!

Hmm. But is he known as Jokerman to others? Sounds like he could clear up this confusion with some nice business cards.

Oh my gosh! I can see that on his sign: “Frog’s Jokebooks”

Uh, yeah. Talk to Frog for 2 seconds and he says his name. WTF caption-writer!!!

Hey there, I’m the caption-writer, and your sound and gentle arguments have persuaded me to change the caption.

Hey there, I’m the caption-writer, and your sound and gentle arguments have persuaded me to change the caption.

A street vending hippie with business cards? His name is Frog.

I’ve changed the caption! We heard from a lot of people about this mistake, thank you for correcting it.

I kind of track this movement personally… from Walter Cole’s Cafe Espresso in Portland to the Lincoln County connection where I lived from 1969 to 1981. There was an old fellow around, then, who was very handy with various crafts- welding, woodwork, mechanics, etc. His name was Jim (?) Galahan… and he had been a Conscientious Objector in WWII, and held at the facility between Waldport and Yachats… and then had continued to live in the area. (I think that facility may have morphed int the Angell Job Corps center.) I remember cleaning up a stretch of Highway 101 on the first Earth Day in 1970… a “big deal”, at the time. I also remember Ken Kesey trying to get a ‘movement’ started in Newport, that he called “Bend In The River”. I don’t recall it having much success, but other “hippie-supported” projects, like the Red Octopus Theater Company (Newport) were quite successful. I was back last year (after 35 years away) and found some of the “old guard” from the ’60s & ’70s still going strong… at the Rainspout Festival in Yachats. ^..^

This is a valuable personal history! Please tell me you have some photos from that time?

I lived on a hippie commune 10 miles south of Florence oregon 1978 ,it was called the Canary ranch .

What was it like?

I have had the pleasure and opportunity to have visited the actual grounds for the Courage Grove Commune. And it was

David, you mention the grounds of Courage Grove Commune. Are there still people living there?

Perhaps updating to include the recent legalization of recreational cannabis would be appropriate.

That’s a great idea!

The Loebner Prize is an annual Turing Test sproenosd by New York philanthropist Hugh Loebner. Dr. Wallace and ALICE won in 2000. The ALICE program was ranked most human computer by the panel of judges.

That’s cool! What’s the connection to the article?