written by Jennifer Nice | featured photo by Talia Galvin

A snag of a branch bobs up and down in the roaring whitewater of Hurricane Creek. In the milky light of dawn, dark green firs and hemlocks hover over the banks of Hurricane Creek as it pours down the mountainside. Daily life vanishes behind this compelling rhythm in the Eagle Cap Wilderness.

An access point for hikers and backpackers entering the Eagle Cap, Hurricane Creek trail is a natural foyer carved by glacial ice over centuries. The trail follows the river corridor with several crossings—a gentle climb through meadows and woodlands. The true grandeur of this wilderness is best captured through experience, a dimension of profundity and immensity lost even in the most expert photos.

Granite ridges and limestone cliffs rise over the trail, and an occasional meltwater rivulet draws a ribbon down their faces. Just minutes up the trail, Sacajawea Peak, and Matterhorn, snow-topped and jagged, appear. Although many people flock to the Eagle Cap Wilderness for backpacking, you don’t have to be a hardcore backpacker to have your own wilderness experience.

This is one of forty-seven wilderness areas in Oregon, from Kalmiopsis in the southwestern corner to Eagle Cap in the northeastern reaches. Only 4 percent of Oregon’s lands are currently protected as wilderness, compared with 7 percent in Idaho, 10 percent in Washington and 15 percent in California. Most recently, in 2009, 202,000 additional acres of wilderness were designated in Oregon, including 127,000 acres in the Mt. Hood National Forest and the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area. The Mark O. Hatfield Wilderness Area expands 65,822 acres along the Columbia River and climbs up to 4,900 feet on Mt. Defiance.

Wilderness is a moving target of conservation and logging, the two interests often opposing. For the past five years, there has been a moratorium in Congress on designating new wilderness areas. Currently, 8,500 acres at Cathedral Rock along the John Day River and Horse Heaven’s 9,200 acres near Ashwood are proposed wilderness areas. This proposal will protect basalt cliff views—critical habitat for steelhead, and a refuge for deer and elk— and provide new opportunities for recreation. Cathedral Rock and Horse Heaven are part of a larger public lands bill that aims to protect several of Oregon’s Wild and Scenic rivers known as the Oregon Treasures Act of 2013. It has passed through the Senate Energy and Natural Resources committee and is awaiting introduction onto the Senate floor.

As vital as wilderness is to survival, it has always been a political slog. This year marks the fiftieth birthday of the Wilderness Act that initially protected more than nine million acres across the United States.

In 1958, an ambitious director of The Wilderness Society, Howard Zahniser, wrote the first draft and was the lead proponent for a bill that would take eight years, eighteen hearings and sixty revised drafts to finally make it to President Lyndon Johnson’s desk for signing. Zahniser died at 58, three months before that momentous pen stroke in 1964.

Before he died, Zahniser, of Pennsylvania, crafted this legal and poetic definition of wilderness:

“A wilderness, in contrast with those areas where man and his own works dominate the landscape, is hereby recognized as an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.”

Today, there are more than 109 million acres and 662 wilderness areas in the U.S. The National Wilderness Preservation System, which includes four types of lands managed by the federal government: National Forests, National Parks, National Wildlife Refuges and Bureau of Land Management. As Americans commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of the Wilderness Act, the best way to acknowledge these unspoiled and protected lands is immersion. Get out there.

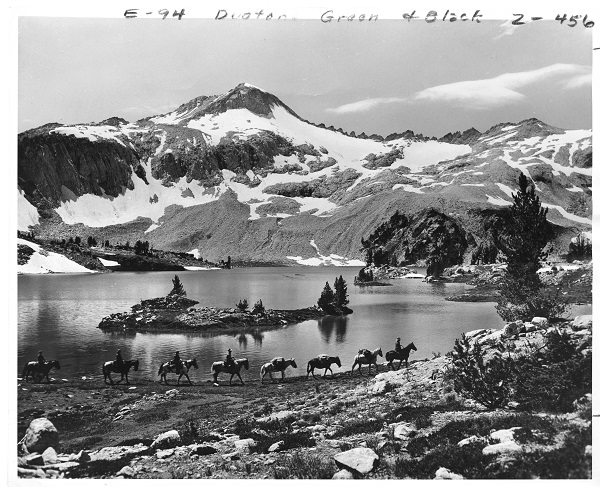

To explore the remote and rugged landscape of these areas you’re either on foot or riding horseback. Wilderness makes no allowance for mechanized vehicles, roads or structures.

Back in the Eagle Cap, at the confluence of Falls Creek and Hurricane Creek, just minutes from the trailhead, the trail picks up on the other side of the creek—a suspended log acts as a bridge over the thundering Falls Creek below.

Dozens of birds are atwitter. Brilliant wildflowers populate their own Monets across the canvas of subalpine meadows. A bumblebee suckles a tangerine Indian Paintbrush. The Eagle Cap Wilderness is a spell of tranquility, untrammeled by man.

This trail offers many shady spots to stretch out and rest in meadows. Some hikers cozy up under solar emergency blankets. Others pack in portable hammocks and string them between noble firs. Small, rustic U.S. Forest Service campgrounds are plotted near wilderness trailheads. The Hurricane Creek campground consists of eight secluded, scenic campsites along the river. Several more campgrounds are tucked along the edges of this wilderness area.

The Eagle Cap is the largest continuous wilderness area in Oregon at 361,446 acres or 565 square miles. Because of its vast 500-plus mile trail system, it offers countless opportunities for solitude and exploration. It has sixty alpine lakes, including Legore Lake, the highest lake in Oregon at 8,950 feet. Four of Oregon’s ten highest peaks (Sacajawea Peak, Hurwal Peak, Pete’s Point and Aneroid Mountain) are in the Eagle Cap, along with eighteen summits above 9,000 feet. Compared to the Cascade Range, which stretches from northern California to British Columbia, such a concentration of majestic peaks in the Eagle Cap justifies it as Oregon’s alps.

“The Eagle Cap is a great example of the Wilderness Act in action,” said Curtis Booher, a recreation manager in the Wallowa Mountains District, which manages 1.3 million acres. “It can be a challenge because the visitation period is so short. We get fifty to sixty groups a day in mid-to-late summer and that’s intense. But the Wilderness Act limits group size to six people, prohibits mechanized vehicles and restricts fires. These help minimize impact.”

Booher noted that generations of locals predate the Wilderness Act, and had once engaged in grazing and logging in the Eagle Cap. But the community as a whole supports wilderness protection. “They love this land.”

Thank you for this well-written article. I was unaware of the Eagle Cap Wilderness, but will now write it on my list of areas I must visit with my cameras.