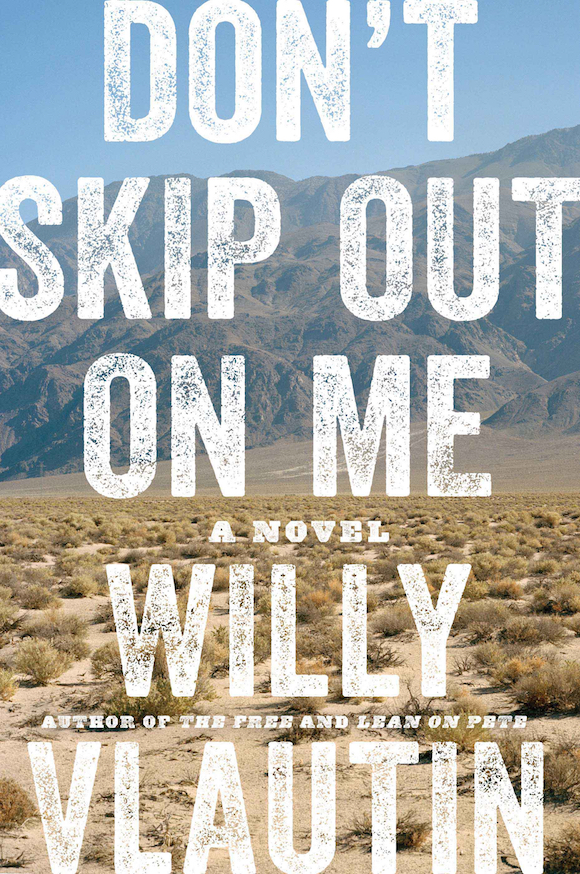

Willy Vlautin talks music, the American Dream and his new book, Don’t Skip Out On Me

interview by Kevin Max

Willy Vlautin grew up in Reno, Nevada, where “dented” people and cheap motels became his muses. His characters struggle in hard lives and tough relationships, often living in motels. Alcohol looms large, providing comfort, escape and plausible excuses in his novels. In 2006, Vlautin wrote his first novel, The Motel Life, and began his career of bringing motel lives into the consciousness of Americans. His ensuing novels include Northline, The Free and Lean on Pete, now a feature film. His new book, Don’t Skip Out On Me, takes us to a ranch in Nevada, where Horace Hopper, a young half-Paiute man, is a sheep farmhand struggling with identity and yearning to become a Mexican lightweight boxing champion. We caught up with Vlautin at his Scappoose home to talk about his writing, the new novel and the last act of his band, Richmond Fontaine.

Tell us how you came to writing.

I was writing bad songs fromage12. I wanted to be in a band so bad. I wrote songs—sadly they were so bad. I was 18 and a big movie junkie. I fell in love with a character or actress or a place. Lost kids in movies were friends of mine. Repo Man affected me in so many ways. I thought that’s gotta be my real dad, Harry Dean Stanton. I got into that movie so much that I tried to get a job as repo man. This is how stupid I was. I went through a dry spell when I was 18 or 19 where I couldn’t find a life to get inside, so I just sat down and started writing my own. I was also reading Raymond Carver around then. He was talking about men who didn’t fit in modern America. I didn’t know that you could be an average, dented guy and write stories, and Carver said that, yeah you can.

This novel takes a deep dive into race identity. Can it be read as commentary on American Indian race identity?

The farther generations get away from where you came from, the lonelier it gets. I always find it interesting when you ask people where you’re from. They say, “I’m Italian,” but their great-grandparents are from Italy. They are Americans or from New Jersey. Race identity is a quick fix. With Horace, race is a quick fix. … He’s a half-Paiute kid who wants to be Mexican. With racial identity, it’s about a quick fix. If I can change the outside, maybe the inside won’t feel so bad.

What about the American Dream in your novels?

If the American Dream is owning a house and being rich and living the capitalistic dream and doing better than your parents, if that’s it, I think it’s in a lot of trouble. As a society, I think we have some ongoing problems that we can’t deal with, especially with the working class. I think we’re getting hoodwinked and robbed.

Don’t Skip Out On Me comes with a music soundtrack. How did that idea come about?

I’ve always loved soundtracks. Two books of mine, Northline and Don’t Skip Out On Me, really felt like music. I set out to make a soundtrack in chronological order as the book progresses. Six months after the last tour of Richmond Fontaine, I called those guys up and said, “I’ve got one more I want to do.” I gave them each a manuscript, and we got together and just did it and we had a blast. You read a book once and you put it on a shelf or give it to someone. But six months down the road, you could be in your car and listening to this and remember Horace or the old man.