Written by Ben McBee

On October 6, 1967, students and faculty at the University of Oregon filed into the Erb Memorial Union at the heart of campus, taking their seats in the ballroom, their eyes locked in anticipation on an empty stage. The room was packed. Its large Friday night crowd was a true indication of the honored guest’s celebrity status – especially considering the excitement and distractions that come with a new school year. A man appeared at the front of the audience, a trail of smoke floating from a loosely held cigarette. His pale face was disguised by dark Ray-Ban shades; a mop of white-blonde hair covered his head. Andy Warhol, the idiosyncratic Prince of Pop Art had arrived in Eugene, Oregon. Or had he?

In the late 1960s, Warhol was at the peak of his fame. From his enigmatic New York City studio, The Factory, Warhol’s artistic, jack-of-all-trades persona was taking the nation by storm. His iconic silkscreen paintings of Marilyn Monroe and Campbell’s Soup cans, along with experimental films, produced cutting-edge commentary about the state of consumerism and pop culture and raised the question of what qualifies as art. Surrounding him was an ever-changing troupe of characters, ranging from Hollywood stars to scholars, wealthy businessmen, Bohemian vagrants and everything in between.

Understandably, it was a pretty big deal when it was announced that Andy Warhol would head out west on a university lecture tour, with stops in Utah, Montana and Oregon.

But, for some unexplainable reason, the real deal seemingly failed to live up to the hype. That autumn night, the man on stage ran through a series of bizarre, grainy clips accompanied by poor audio, which caused many attendees to get up and leave. Following the presentation, the pallid figure proceeded to answer questions from the perplexed spectators in an equally bewildering, nearly incoherent manner.

It’s safe to say more than one person left the experience scratching their heads, wondering what in the world they had just witnessed. But as the freshness of UO students’ puzzlement settled in, the seeds of suspicion began to take hold in the Rockies at the University of Utah – Warhol’s first scheduled stop – where it eventually blossomed into a full-blown scandal.

Joe Bauman, then an editorial assistant with the Daily Utah Chronicle, the school’s newspaper, was scheduled to meet with the celebrity artist at the airport and planned to interview him on the ride to campus. In his recollection of that day, Bauman wrote for the Deseret News,

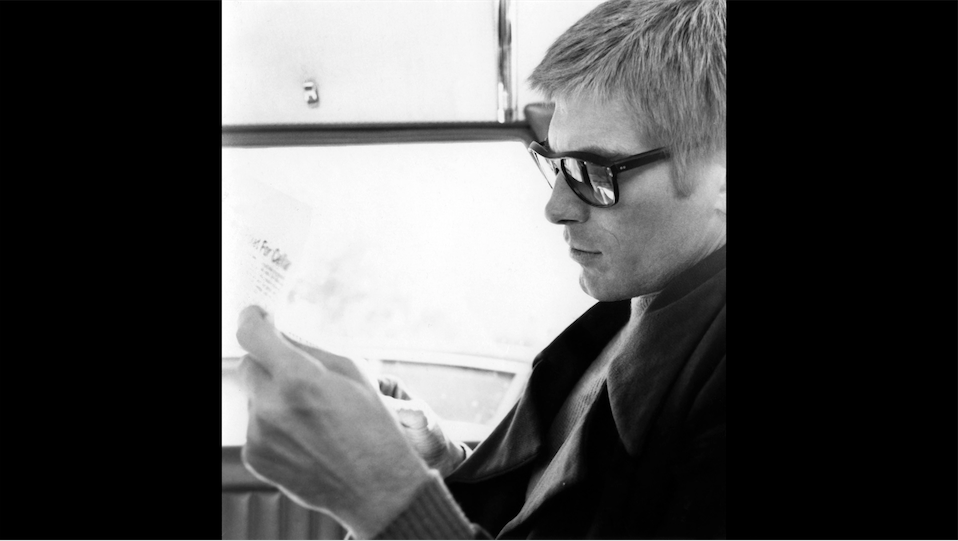

I do recall two events at the airport: first, a cloud of white dust blew off Warhol’s hair, which I took to be powder he had sprinkled on as decoration; second, someone with him insisted that I absolutely could not take a photograph. Warhol was far too shy.

Considering the story over the interviewee’s bashfulness, Bauman handed a newspaper previewing the speech to Warhol, then proceeded to discreetly snap a profile photo of him with the Mamiya C3 twin-lens reflex camera in his lap. Following Warhol’s similarly bewildering performance in Salt Lake City, this image became the centerpiece of an investigation that alleged the superstar in question was in fact a phony all along.

Four months later, all of their suspicions were validated. Hearing concurring stories from multiple sources, Don Bishoff, a reporter for the Eugene Register-Guard, acquired the number of the payphone inside The Factory and decided to call up Warhol to get to the bottom of everything, once and for all. Warhol oddly confessed that his associate, an actor named Allen Midgette, had in fact gone on the circuit in his place. “He was better than I am,” Warhol explained to Bishoff. “He was what the people expected. They liked him better than they would have liked me.”

Warhol’s camp was paid more than $2,500 for the fraudulent foray that left a sour taste in people’s mouths. It was later revealed that Midgette was allowed to keep all of the profits, which he used to fund an excursion to Europe. It turns out he had not been paid for acting in several of Warhol’s movies.

Nonetheless, Warhol was invited back to the University of Oregon campus on February 21, 1968, this time accompanied by his manager Paul Morrissey and actress Viva. After solemnly swearing that he was indeed himself, Warhol proceeded to share segments of his 25-hour motion picture, which included simultaneous projections and superimposed scenes of Vietnam protests and sordid affairs.

Though all of the madness likely vexed more than a few, Warhol was successful in increasing the mystique of his personality, showing how life can be turned into a performance at any moment. His escapade became national news, and while he might not be for everyone, the enrollment of UO’s class on underground films jumped from sixty-three to 350 that year for a reason.