Written by Eric Mertz

If you squint hard enough, you can almost force the asphalt to fade away and replace it with a battered territorial road. Picture a sawmill off in the grassy distance. Follow the gentle billows of smoke as they rise and vanish into gray sky.

Open the window—you can still smell fresh cut wood in the air.

The knotty hills and hollers along Highway 42’s looping path between Roseburg and the southern Oregon coast beg dormant imaginations from their slumbers. They force a glance over the shoulder as far back as a generation or more.

For the better part of a half-century spanning settlement to the early twentieth century, the Sawdust Circuit delivered a unique brand of barnstorming baseball to southwestern Oregon. The informal league forged bonds between the communities of people who settled this area and infused the future national pastime with a pioneer spirit.

The term “sawdust circuit” comes from outside baseball. Originally, it was an idiom indicating a route taken by a traveling evangelist preacher. Around the turn of the nineteenth century, the knight of the road was still a vivid figure in small-town American life. Traveling vaudeville and circus shows came around a couple of times each year. Salesmen would arrive on the morning train with showcases full of tantalizing new products, new shoes, fabrics and snake oils. This time ushered in an entire lexicon around traveling vagrancy, hobos and drifters. Much like religion and commerce, baseball used to come and go as temporary respite on Sunday afternoons.

Accounts of baseball’s barnstorming era are scarce. Most historians gloss this chapter over, perhaps because it is too obscure or it lacks the glamour of later eras. Consequently, much of what survives from the Sawdust Circuit comes in bits and pieces, a periodic re-gathering of faded pictures and yellowed paper. What is there has been pieced together slowly over time, attic by attic and family archive by family archive. The Sawdust Circuit is a people’s history without

established chronicle, only derived through reassembly.

Photos courtesy of Coos History Museum

The present-day data-heads who track baseball minutiae won’t find much to analyze in this ramshackle oral history. Player greatness is anecdotal. The Paul Bunyan-esque feats of strength have been passed down without box score or stats—we hardly even know the player names, except when scrawled into a postcard.

The ball fields found in the Sawdust Circuit hardly resemble the European-inspired castles of their big city counterparts. There was no Ebbets Field along the muddy banks of the Coquille River. Instead, the game was played on makeshift diamonds, and attendees sat in wooden bleachers constructed in a semi-circle behind home plate. There were no dugouts. Players stood side by side, fans looking over their shoulders at the developing play. There were no groundskeepers to mow and tend to the weeds that cropped up in the outfield, though someone was on duty to extinguish fires, often started when errant cigarette or pipe ash sparked in the dry grass or the tinderbox bleachers themselves.

Looking back at the pictures, it is the omissions we first notice—no light towers looming over the field, no concourses. There wasn’t always a proper outfield wall to serve as the boundary demarcating in play or out. An old faded photo reveals an outfield lined with men wearing suits and women in flamboyant hats sitting on blankets. The unlucky fielder would circle around under the ball, bearing slurs and taunts from the hecklers for whom admission came with a right to wreck havoc. A few yards behind first base, horses graze in the shadow of a barn.

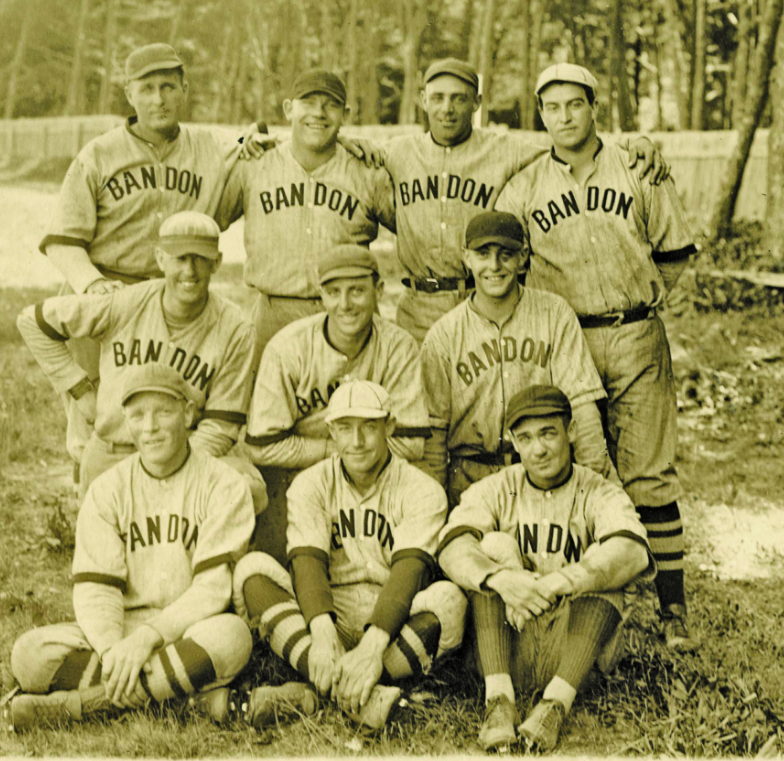

On a postcard dated October 11, 1898, the Norway Baseball Team poses in front of a split rail fence on the morning before a game. The nine men are all of medium height and medium build, wearing stern expressions that could hardly be mistaken for a smile. In another surviving team picture, the boys from Bandon are all smiles, linked arm in arm like brothers. A few of them appear small—one looks to be no older than high-school age. As long as the player could throw the ball, run and hit, and didn’t have chores that demanded attention, he was fair game. These players were rugged, hardly what we would call, by today’s standards, athletic. Players throw harder now. They hit the ball farther. Looking at these boys, it’s not hard to see why. Most striking again, however, are the omissions.

There are no black faces. We see none of the Latino and Asian players that define today’s international game. Baseball has often been called an immigrant’s game, and these boys are indeed immigrant sons, sired from a generation of pioneers that crossed the unexplored country on the Oregon Trail. The heyday of the Sawdust Circuit existed more than half a century prior to Jackie Robinson breaking the color barrier in 1947. A highly competitive Negro league cropped up in communities all across the country, but the history of black barnstorming players is segregated from white, just like the professional game was.

The ball teams were often formed out of the places where men worked. Around 1912, there was a prominent team from the coalmine camp up in Beaver Hill. The Coos River teams were comprised mostly of local farmers. The teams took nicknames, some curious and some familiar. The Blue Ridge Tigers came from the McDonald and Vaughn logging camps. The Powers Cubs had two baby bears as their mascots. In a uniquely Oregon twist, there was a team organized from one of the local fish hatcheries.

Players were not organized. No one was paid a salary, at least not much. The most money changing hands over a game likely came in the form of a wager between two owners, or well-to-do fans seated out on the berm. Local mogul Al Powers once offered a $5 reward for the first homerun hit in his park, eventually given to Myrtle Point banker Harry Dement, who was said to have cranked the ball a mile. Edwin Charles “Snake Charmer” Tomlin was a pitcher for the Portland Beavers of the Pacific Coast League, which at the time was considered a high-quality professional league. Tomlin traveled through Riddle to look at property on one of his days off when someone thought it would be a hoot if he suited up for the local barnstorming team. The opponent would be none the wiser. A colorful character, Tomlin took the offer, hitting a homerun and dazzling opponents with his pitching before getting in his car and driving back home. Those opposing farmers likely didn’t know what hit them. During the Depression, near the end of the Sawdust Circuit, players from the newly formed Civilian Conservation Corps camps would suit up against local loggers who wore the same overalls on the field that they wore to work. Accounts of these games described them as particularly rough and tumble, often ending in fisticuffs that garnered cheers as hearty as homeruns.

Sunday baseball came with the promise of big bands and barn dances following the games. Wide-eyed fans brought their own food. Certain women were known to give a fresh, home-baked pie to players who hit a homerun, a welcome bonus that surely would not go wasted. Games were often advertised in handbills and flyers and newspapers with honest, simple promises such as “A good time is assured.”

Schedules in the Sawdust Circuit were scattershot and travel difficult for both players and fans. Wagon and car rides got teams across relatively short distances. In August 1916, a rail connection between the south coast and Eugene was established. Trains made longer distances easier, though not by much. Fans often went by boat. On Sunday mornings, baseball fans would line up on the river docks to board sternwheelers heading up the Coquille River to McKnight Field near South Fork. Typically 400 revelers would get on the Dispatch with picnic baskets in hand; sometimes as many as 150 would travel on the Telegraph.

The end of the Sawdust Circuit is as ambiguous as the rest of its history. Its dissolution ties in with many other societal trends, all happening concurrently.

Baseball changes due to industrialization

Industrialization and wars forced rural America to reinvent itself, and no town was immune. Churches formalized. The traveling salesman was replaced by the downtown department store and later, the mail order catalog.

Baseball was evolving as well. The national pastime remained as popular as ever during the tenuous years between World Wars; how the sport was delivered to its rabid audience, however, changed radically. Up until this point, big-city newspapers would give World Series play-by-play updates via telegraph. A town crier would then read the results to the patient crowd of waiting fans. Radio modernized that. Within a few years of the end of the Great War the World Series found its way onto the airwaves.

As more locals had radios available to huddle around and listen to the exploits of mythic players like Babe Ruth, the audience for the iterant brand of baseball winnowed away. The Sawdust Circuit managed to hang around a little longer than most barnstorming leagues, perhaps because of southwestern Oregon’s relative isolation from large cities like Portland and San Francisco, but by the time America entered World War II, it was gone for good.

Part of the tragedy in the demise of barnstorming baseball is how it coincides with the decline of small town cohesion. Rather than growing up with a determined vision of fleeing the farm, young people rooted for neighboring farmers, clad in their town’s jersey.

The fields where the Sawdust Circuit thrived are today, for the most part, overgrown, fallow or paved over. Norway, Oregon is an anachronism now, aside from a few antique reminders. There is no town of Blue Ridge anymore. City softball leagues organize company teams, but aside from loyal wives and husbands and a few bored kids, it hardly stands as entertainment. Some chapters of history, once closed, stay closed.

A few sawmills remain in southwest Oregon. They kick up the same aromatic dust and deeply satisfying industrial cacophony that once defined the whole region. Passing through these hills that cling tightly to their secrets, you have to look a little closer to see the remnants of that legacy. Narrow your eyes a bit. There may just be a game up around the bend.