written by Lee Lewis Husk | photo by Jake Stangel

For most americans, the gateway to healthcare is through a job, turning 65 or poverty. But what about the unemployed, the young and the working poor? About 637,000 Oregonians in 2008 were uninsured — 16.8 percent compared with 15.4 percent nationwide. Excluding those 65 and older who qualify for Medicare, one in three Oregonians had no health insurance between 2007 and 2008. With soaring unemployment, Oregon had the 12th highest uninsured rate in the country, according to the Oregon Health Policy and Research office.

In an era when health care costs are far outpacing our ability to pay for them, where do people go when they break a leg or develop diabetes? Who takes care of them?

The current trends don’t offer much comfort. People are out of work. The Oregon Health Plan for low-income people has a waiting list. Family health insurance premiums have shot into the stratosphere, averaging $1,049 a month in 2008 compared with $467 in 1998. Businesses are either dropping health insurance or shifting more of the costs to their employees.

Even those with insurance can’t always get care, especially if they are geographically distant from clinics and hospitals or because high co-pays and deductibles cause them to delay or forego preventive services. Plus, the high cost of medical care foreshadows bankruptcy. This is reality.

In this feature, 1859 profiles three extraordinary medical practices that care for people regardless of their ability to pay, plus a collection of physicians who are taking their expertise and that generous ethic abroad.

A common thread between these medical providers is that they have found ways, or donated their time and expertise, to bring critical health care to people who would not otherwise be able to pay for it.

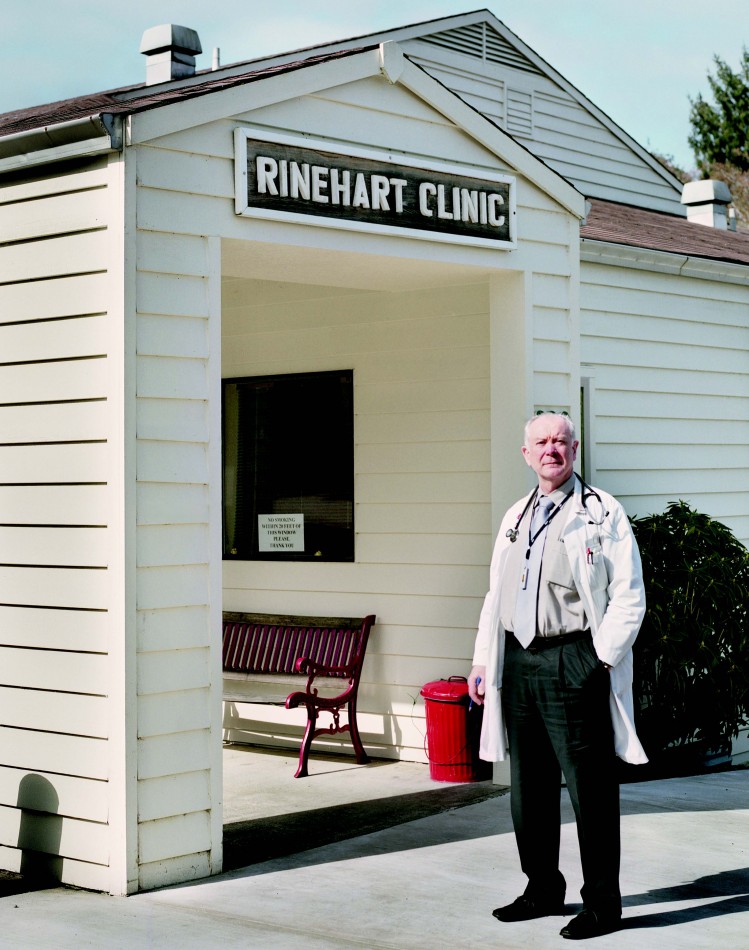

Rinehart’s Rural Clinic: A Century of Service

“Grandpa developed a formula for treating arthritis that was very effective,” recalls Harry Rinehart, M.D. “We don’t know what it was, but he told people it was clam juice from Nehalem Bay.”

Harry is the third generation of Rinehart physicians to care for people in north Tillamook County. In addition to his grandfather, his parents, Robert and Dorothy, both M.D.s, practiced in the small coastal community of Wheeler. Harry chose to practice in Prineville until the U.S. Army Reserves called him to serve in Desert Storm. In 1992, he returned to Wheeler where he faced a personal dilemma.

The county has twice the national rates of poverty and elderly, “giving us a high burden of illness,” Rinehart says. A private practitioner would have to limit service to the poor to sustain a medical practice; yet Rinehart couldn’t imagine turning away old friends and neighbors whose taxes supported his education and the benefits it gave him.

His solution was to open a private, nonprofit organization run by a board of directors. The Rinehart Clinic opened in 1996, the only full-time medical practice between Seaside and Tillamook. “We struggled financially at first,” Rinehart recalls. “Sometimes I went without a paycheck, or coughed up some money to cover the payroll.”

“We struggled financially at first. Sometimes I went without a paycheck, or coughed up some money to cover the payroll.”

– Harry Rinehart, M.D.

With improvements in billing and collection, and rising patient volumes, the clinic began to thrive in the early 2000s. Today it is one of the largest employers in the area with about thirty employees. It records 13,000 visits a year from residents and tourists. Patients are seen on a sliding fee scale, with charges as low as $5 a visit. In 2008, it became a Federally Qualified Health Center, which gives it higher reimbursement rates from Medicare and a federal grant of about $120,000 a year.

The nonprofit status allows the clinic to solicit donations. Rinehart calls it his favorite charity. “I give more to the Rinehart Clinic than to any other organization—and I enjoy it. I don’t mind at all asking community members for $10,000 and up, because I’ve given more.” Donations range from as little as $10 a year to $50,000.

“He’s a Renaissance man, an Oregon native and a highly-skilled primary care physician,” says Leila Salmon, current board chair. “And his letters of appeal show evidence of his heartfelt dedication to the community he serves.” In 2009, donors gave more than $100,000 for the clinic.

“Rural clinics are key to getting health care to residents in rural areas,” says Robert Duehmig of the state Office of Rural Health. “Without them, people would have to drive great distances to get what care they could. Rural clinics survive because of people like Dr. Rinehart. I wish we could clone him.”

Rinehart, 64, says he can’t imagine doing anything else. “We’ve resurrected a rural health care delivery system that is second to none, and we’ve done what the nation hasn’t been able to do—provide care to everyone who graces our door.”

Volunteers in Medicine: Clinic of the Cascades

Back in the 1970s, when the rest of Oregon was experiencing physician shortages, Bend enjoyed an enviable influx of doctors. But what do all those docs do when they retire?

Ronald Carver, M.D., an obstetrician/gynecologist who came to Bend in 1974, heard about a clinic in Hilton Head, South Carolina, that used retired health care professionals and community volunteers to care for the local uninsured population.

Carver and several community leaders visited Oregon’s first VIM clinic in Eugene and then sent letters to area health professionals asking if they would participate in a free clinic. The response was “unbelievably positive,” says Carver. With a parcel of land from St. Charles Medical Center, a large anonymous donation and community funds to build the clinic, and pledges of time from countless clinicians, VIM started seeing patients in 2004.

In Deschutes County, where today 19 percent of residents are uninsured, Volunteers in Medicine (VIM) Clinic of the Cascades fills a huge gap in the lives of thousands of patients.

As a team, we’re making a real difference.

– Ronald Carver, M.D., Founder of Volunteers in Medicine Clinic of the Cascades

“Bend is unique,” says Carver, who served as VIM’s first medical director. “This type of clinic can’t happen everywhere.”

The clinic, which receives no government or insurance funding, exists almost entirely on the largess of local businesses, individuals and hundreds of volunteers. To avoid overlap with other programs, VIM serves the working poor—people who don’t qualify for the Oregon Health Plan, Medicare or whose employer doesn’t provide insurance. Since 2004, VIM has cared for more than 6,000 of these people. The clinic expects to see about 2,600 patients in 2010, according to Kat Mastrangelo, executive director. Although this is about the same number of patients VIM saw in 2009, the number of visits will increase because its patients are sicker and now average five, rather than three, visits a year. The clinic is at capacity, she says.

Other VIM clinics that don’t have Bend’s large retired population and volunteers typically have higher staffing costs. Nearly half of the volunteers are retired physicians, nurses and other health care practitioners. In 2009, VIM’s 295 active volunteers logged 22,366 hours. The clinic raised $729,285, with 57 percent coming from individual donors. VIM estimates that it donates $2.5 million worth of service, pharmaceuticals and pro bono care each year.

The facility focuses on primary care and coordination of specialty care with a network of 185 specialists who accept VIM patients by referral on a pro bono basis.

Carver, who retired in 2001, emphasizes that the clinic couldn’t happen without community-wide support. “As a team, we’re making a real difference,” says Carver.

Brave Women of Ethiopia

In february, five oregon physicians took temporary leave from their jobs and boarded planes for a destination half a world away to stitch together the lives of twenty-seven women. They were broken by poverty, lacking education and had no access to decent health care.

For six days and nights, the Americans worked indefatigably alongside local doctors and nurses in a hospital in rural Gimbie, Ethiopia to heal women with uterine prolapse, an injury of obstructed labor and hard physical exertion. Many of the women had walked for days, lining up outside the little seventy-one-bed hospital for the chance to live without pain and the social stigma that comes from having unhitched female parts fall to the outside. It’s a condition rarely encountered in the West where women have access to prenatal care, birth attendants and surgeons to perform emergency C-sections.

“Women walk from sunrise to sunset, carrying huge loads of wood for fuel, water and kids on their backs,” says Ethiopian-born Rahel Nardos, M.D. She left the country seventeen years ago for a chance at an American education. Now 35, she’s in a urogynecology fellowship at Oregon Health & Science University, reinforcing her education with the skills and knowledge she needs for this and future missions to her native land. “If women are unable to carry these loads, their families sometimes abandon them, or their children might have to fend for themselves,” she says.

In just two hours in Gimbie, Philippa Ribbink, M.D., saw four cases of severe prolapse – about the same number as she’s seen in twelve years of practice. “The amount of prolapse there was unbelievable,” she says. She and Kimberly Suriano, M.D., both obstetricians/gynecologists at Everywoman’s Health clinic in Portland, were in Ethiopia for the first time, part of a team of Oregonians hoping to establish an ongoing relationship with the Gimbie hospital.

It was really sad to see the many women we weren’t able to provide care for after they had walked for hours to reach us. — Rahel Nardos M.D.

Word of the American surgeons’ presence in Gimbie spread quickly, and soon the hospital had far more women than it could help. “It was really sad to see the many women we weren’t able to provide care for after they had walked for hours to reach us,” Nardos says.

With the right care, this condition can be prevented through family planning, midwifery and nurse training, community outreach and education, and pre- and post-natal care and emergency obstetrical care.

Nardos hopes that OHSU and the Gimbie hospital can establish an ongoing collaboration, where OHSU physicians experience health care unlike anything they’ll see at home and Ethiopian women get their lives restored.

“After surgery, one patient sounded like she’d been reborn,” Nardos says. “She was kissing everyone and hugging us—she was so grateful.”

The Oregon team, which also included OB/GYN Michael Cheek, M.D., of Lincoln City, and his brother David Cheek, M.D., a Portland-based anesthesiologist, taught two local doctors the latest techniques of prolapse repair so that they could continue doing cases after the Americans went home.

Because of the extreme overcrowding and lack of nurses at the hospital, the women who had prolapse surgery were discharged after just two days. Women in the West who get this type of repair are advised not to lift anything more than five pounds for two months. Nardos knew that they’d be lifting heavy objects soon after the surgery because their lives and their children’s lives depended on it.

“What kind of brutal doctor am I to send women home after two days,” Nardos asked after returning home. “But I know that I didn’t have a choice. We had to be conscious of not abusing their system and making sure patients left on time.”

Salem Physician’s Mantra: Whatever it Takes to Help the Children

James Lace, M.D., pauses midway through a telephone interview, and says, “I’m buying a lottery ticket now.”

If he wins the jackpot, he has big plans: help more orphans and homeless kids in Tanzania, bring clean water to Maasai villagers and set up rotations in Tanzania for students from Oregon Health & Science University, Western Oregon University and Pacific University.

His international humanitarian work follows decades of advocacy for children in Oregon. Lace, 61, started Childhood Health Associates in Salem in 1977, fresh from a pediatric residency. The clinic’s staff, he says, really pushes the envelope for kids. Unlike most clinics that adhere to a formula for profit, Childhood Health Associates doesn’t limit the number of poor or under-insured patients it sees. The clinic also employs four full-time interpreters to serve the third of its patients who are Hispanic. About 60 percent of its patients are covered by the Oregon Health Plan, 30 percent have commercial insurance and the remainder of patients pay out of pocket.

The clinic never allows the lack of money to prevent children from getting their vaccines or other needed services, Lace says.

Advocacy for him starts with two questions: Why are kids dying and what can we do to prevent children from dying? He has successfully lobbied the Oregon legislature to require child safety seats, bike helmets and to give newborns vitamin K to prevent bleeding. In 2009, he was instrumental in the successful passage of the Healthy Kids Plan, the state’s landmark law providing health coverage for all Oregon children.

The clinic never allows the lack of money to prevent children from getting vaccines or other needed services. – James Lace, M.D.

Lace’s mission hasn’t gone unnoticed. His colleagues have nominated him for a prestigious award with the American Academy of Pediatrics. The Oregon Medical Association named him 2006 Doctor Citizen of the Year, and the Marion-Polk County Medical Society honored him with the President’s Achievement Award.

In 2001, Lace went to Tanzania as a doc on a climbing expedition to Mount Kilimanjaro and “got sucked into the tragedy of HIV-affected orphans.” He asked himself, “How can I walk away?” He couldn’t, and now Lace travels to Africa a couple times a year to help get kids off the streets, off drugs and into vocational training. He volunteered with Medical Teams International in tsunami-ravaged Sri Lanka in 2005 and 2006, and is currently waiting to hear whether he’ll be part of a medical team to Haiti.

The 2010 Oregon legislature passed a resolution commending Lace for his service to children locally and internationally. One of the resolution’s sponsors, Sen. Jackie Winters, of Salem, has been on missions to Africa with Lace and says that “he contributes so much in this country and now he’s taking [his work] abroad.”

The Lace resolution notes thirteen deeds, each one a selfless act of caring in a long and distinguished mission spanning thirty years.

Hearts reaching out…nothing more beautiful than that!!