written by Max Giffin | photos by Division of Special Collections, University of Oregon

James Dormeyer was born three hours northeast of Paris in the Lorraine region of France. Just across the German border, the Lorraine Valley, was, in 1944, occupied by German forces. When Dormeyer was 8 years old, American troops led by Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower liberated his hometown.

“The fascination for everything American ran back to my childhood because my grandfather often told me the story of the fairy Vivianne who would take good children with her on a winged duck all the way to California,” he said. “And when later, in 1944, American soldiers arrived to liberate my town and country and also give away chocolates and chewing gum, I was sure that most of these soldiers had come from California and could be nothing but nice.”

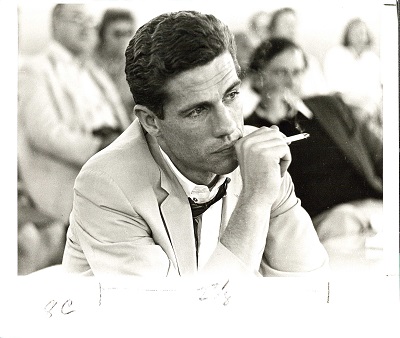

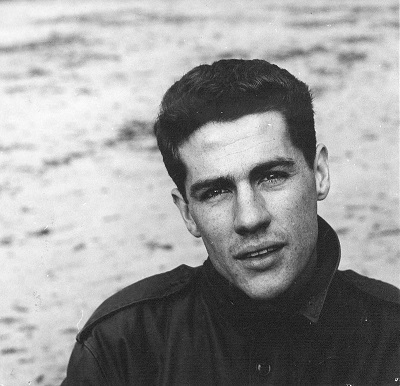

James Blue, said Dormeyer, effortlessly countenanced these childhood images. “He was the America one dreams of. He had the beautiful face of America, an America spontaneous, tender, almost naive, bold and contradictory.”

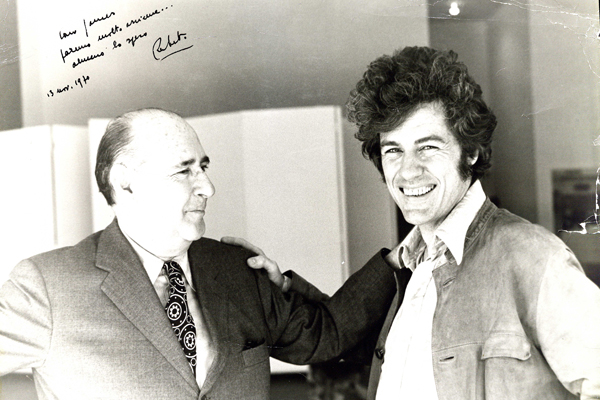

Dormeyer met Blue in 1957, when they were students at the prestigious film school, L’Institute des Hautes Études Cinématographique (IDHEC). They bonded as outsiders, non-Parisians in Paris.

Blue would go on to become the first American to win the Critics Award at Cannes Film Festival for a film he made in Algeria and be nominated for an Oscar for his work on a documentary in America. These films—indeed his whole career—centered on using a Super 8 camera as a tool to lift up disadvantaged populations.

Blue was born in Oklahoma, then raised in Portland. He took Latin from Jefferson High’s last Latin teacher, Irene Campbell, and trod the boards to the delight of drama teacher, Melba Sparks. In 1952, he graduated from University of Oregon with a major in theater, was awarded a Fulbright scholarship and moved to Paris to attend IDHEC. He made films on five continents, won the industry’s highest honors, interviewed the top directors of that era (Roberto Rosselini, Alfred Hitchcock, Frank Capra, Jean-Luc Godard and others), taught film at Rice University, UCLA, SUNY Buffalo and England’s National Film School. He achieved all of this in half a century.

“He had five different directions he could go, and he did,” said his brother Richard Blue, 78.

To talk about the life of James Blue is to explore many extraordinary lives under one roof. He was an actor, a filmmaker, a journalist, a teacher and an activist. He spoke French, Dutch, German, Arabic and, maybe, Italian. He died at 49, when he was planning to return to feature filmmaking with one of his most ambitious and troubling projects.

Almost thirty-five years after his death, University of Oregon has just begun collecting, documenting and preserving the effects of Blue’s life. They graciously opened these archives to me. At the top of the Knight Library and in the special collections room, I spent an entire day reading countless interviews, letters, articles and sifting photographs to immerse myself in Blue’s world. In six hours, I merely scratched the surface of four of the seventy-two boxes chronicling this extraordinary life that went in many directions.

Les Oliviers de la Justice

Blue, as a Filmmaker

“I had all of the questions and none of the answers,” Blue observed in one of his documentaries. His questions began with a truly curious “why” and a Super 8 camera, not a pre-ordained answer disguised as a question mark.

In the post-Depression, post-WWII era, the tattered world offered countless threads to explore and remedies to question. Blue took his camera, or any recording device, and began his investigation. In the United States, the Civil Rights movement was under way. Congress was in a full-blown witch hunt for Communists, and urban development was done without a conscience. In Algeria, the century-long French occupation was coming to a bloody end as Algerians fought for independence from their unwanted French hosts.

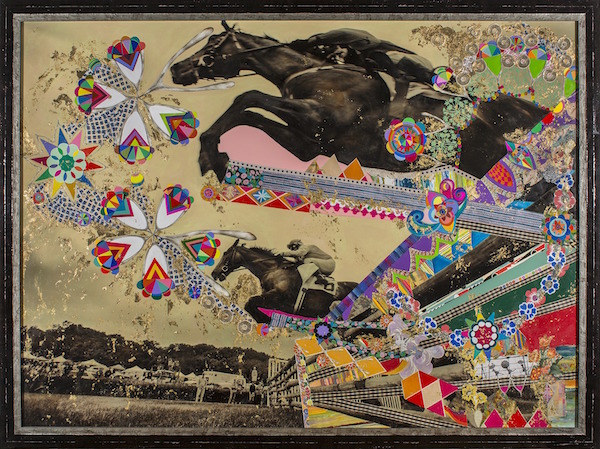

As a young filmmaker, Blue saw the opportunity in a novel from Algeria-born Jean Pélégri, Les Oliviers de la Justice, translated as The Olive Trees of Justice. The recent graduate of IDHEC would bring new documentary film techniques that pushed the boundaries of “participatory” documentaries and cast the French occupation in a new light by using non-actors to tell the story.

“What I was trying to do in The Olive Trees was to avoid any kind of fabricated emotion,” Blue said in a 1963 interview. “Of course, I’m not trying to say I didn’t want emotion in this film—that would be completely contrary to my goals—but I wanted to bring about emotion by a synthesis of authenticity in the décor, in the actual setting, in the things that real people said, in the way real people looked, where they lived, in a juxtaposition of all that, a development of the old idea of ‘montage of attractions,’ along a certain theme.”

His questions began with a truly curious “why” and a Super 8 camera, not a pre-ordained answer disguised as a question mark.

This film, made in 1962 during the Algerian war of independence, was fraught with both physical and professional perils. Blue’s reaction was more detached and academic than emotional. “[The Organisation de Armèe Secréte (OAS)] attacked our studio with dynamite—four times at night and once at noon. That time they put it in our sound booth when we were all next door in the projection room: two and a half kilos of rock quarry dynamite and two rifle grenades and two phosphorus bombs, and they lit the fuse. Only the humid Algerian climate saved us. They’d evidently hidden their dynamite underneath their car. It was out all night, and it was wet—only the powder was burned up—it didn’t go off.”

Critics from France denounced The Olive Trees as being overly apologetic to Algerian rebels. Those inside the Algerian independence struggle thought the film too kind to the occupying French army. The filmmaker saw it all through a different lens.

“The parallels between Algeria and America were enormous as far as I could see, not only from the racial standpoint – the race problem had a different aspect there; it wasn’t a color problem, but nevertheless, it was pretty acute,” Blue observed.

The French film aristocracy at the Cannes Film Festival would have the definitive judgment, awarding the film with its esteemed Critics Prize, a first for an American director.

Many years later, when the film was subtitled in English and screened in New York, it experienced a second public life. “It’s a good picture, in many ways striking … Mr. Blue should certainly be making films somewhere,” offered The New York Times film critic Howard Thompson in 1967.

By the time Thompson had typed his last sentence, James Blue, then 36 years old, had already made more than a dozen films, including The March, a strikingly beautiful documentary about the 1963 peaceful civil rights protest in Washington, D.C. and the beginning of his Oscar-nominated film, A Few Notes on Our Food Problem, an apocalyptic glimpse at the world’s future food crisis.

In the scant thirty-three minutes of The March, Blue captured the emotion behind the American journey of a people walking into the headwind of racial disparity toward something better. In making The March, Blue was particularly keen not to merely rubber stamp progress that African Americans had made since slavery. He recognized this as a false summit and dishonest propaganda.

In a proposal to the United States Information Agency for The March in 1963, Blue discusses his true motives for making the film. “I would like to show the difficulties involved in uprooting prejudice. Instead of talking about the evolution and ‘progress’ of the Negro, I want to talk about the evolution of his struggle and the slow and cumbersome but certain evolution of the white man’s mind.”

Arthur Schlessinger Jr., the Pulitzer award-winning American presidential historian, boasted, “The March will go down as one of the great American documentaries.”

When Richard Herskowitz, the director of Cinema Pacific at University of Oregon, recently learned about Blue from colleagues in the industry, he launched a film series devoted to Blue. “I was blown away by his films,” Herskowitz said. “James Blue reinvented himself with every film. There’s no single filmmaker I would compare him to. There’s no one else like him.”

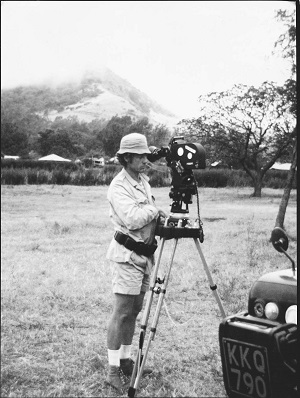

Kenya Boran, 1974

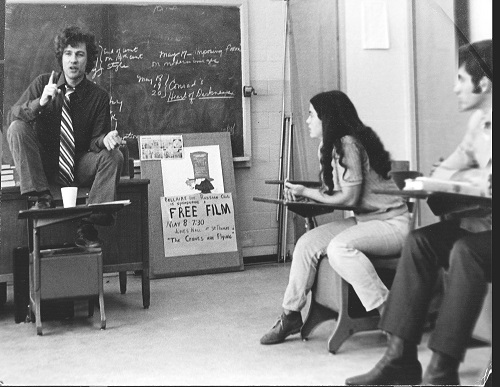

Blue, as a Teacher

In 1980, a student of Blue’s from SUNY Buffalo received a $30,000 grant from the New York Council for Humanities to make her film, Love Canal. That spring, she wrote in a letter to Blue: “I want to thank you, if you will sit still for it, for teaching me, but also for keeping an eye on me, criticizing, yelling, screaming and pushing me …”

Many of his colleagues were shaken by how quickly Blue had sidelined his career of filmmaking to take up the related profession of teaching it to others. For Blue, though, this was more of a distinction without a difference. His ultimate motivation was to empower people through film. His tool was the Super 8 camera. His audience remained the same—curious and critical minds.

Blue had a knack for teaching film. In the 1960s, film largely remained in the category of something that people with considerable funds and considerable time did rather than taught. Hollywood and its stars were larger than life but miniscule and exclusive for industry jobs.

“He believed that the center of college education was the creation of the responsible citizen concerned about his or her community, and that, in media, ‘the key concept was its democratization in terms of promoting general awareness and providing access to the materials,’” said Gerald O’Grady, a colleague who founded The Media Center in Houston, Texas and the Center for Media Study at the State University of New York at Buffalo.

Until the advent of the small and inexpensive Super 8 camera, film schools were still sparse in the United States. There were, of course, concentrated centers for film in California and New York but few film schools in between. With 8-millimeter-wide film and Super 8 cameras, James Blue began a popular revolution that began at Rice University, continued at SUNY Buffalo and all of the places in between New York City and Hollywood.

Instead of training people for a more

than doubtful Hollywood career, we can

channel them towards this awakening of

a community conscience.

Inside and outside of the university structure, Blue began theorizing and then creating programs where he could empower others to shoot film and be heard. In Houston, he had soon founded a communal cinema project for minorities called the Southwest Alternate Media Project. “We’re in the process of developing a completely new field of activity, and I don’t mean just us in Texas. Film centers are springing up all over the country,” Blue said in an article he wrote in 1976. “Instead of training people for a more than doubtful Hollywood career, we can channel them towards this awakening of a community conscience. There’s plenty of work for everyone.” This program is still active today.

Blue’s most valuable characteristics as a teacher were what Dormeyer called, “almost naive, bold and contradictory.” He brought top directors to his classes, screened their films while omitting crucial scenes, then asked his students to create and discuss their own ideas for the missing scene. Often initially awkward for the established director, these sessions brought new ideas and engaging conversations.

The famed Australian ethnographic filmmaker, David MacDougall, who worked with Blue on the documentary Kenya Boran, in 1974, said that he did not think that it was possible to teach film production until he saw Blue do it.

Perhaps Blue’s sacrifice of his own development as a film director was premature, but his inspiration as a teacher brought a new wave of new filmmakers who would build on his tutelage. From a purely practical perspective, if Blue had taken the more traditional path of waiting to teach at the culmination of his career, his early death would have robbed his students-in-waiting.

“Blue was a born teacher, but he was a ‘made’ film-maker,” Colin Young, the first director of the British National Film School, said in a 1980 article in Sight and Sound international film magazine. “He was one of a small band of people I have known and worked with who had what Arthur Ripley once called ‘the muscle that senses what an audience’s reaction is likely to be.’”

Blue, in the edit room

Blue, the person

While Blue outwardly radiated success, his inner life was a constant struggle. “In James, there was an internal civil war,” his brother, Richard Blue, said. He was born at the beginning of the Great Depression to a father who did architectural renderings and a mother who feared Communists and liberals.

“We had a mother who was a stern Protestant from Oklahoma,” Richard Blue added. “She was one of the first members of the John Birch Society. She loved James but didn’t know how to deal with his creativity.”

Blue took off for France and soon began making films about oppressed populations in Europe and Africa while McCarthyism raged back home.

His mind was never quiet. His head was brooding grounds for ideas, refinements and more brooding. “While he was living with us this year in London, he had the reputation of being the only person we knew who continued a sentence in the morning that had not ended properly for him the night before. Then, maybe then, he might say good morning. But probably not. He had too many things on his mind,” observed Young.

Jim would get on a plane with Tex-Mex food and a bottle of scotch and show up at

Richard’s door. ‘I want to find out what you know about this topic.’

—Richard Blue

His obsession would even take the form of cross-country flights in search of suitable answers. While Richard Blue was teaching at University of Minnesota, occasionally Jim would get on a plane with Tex-Mex food and a bottle of scotch and show up at Richard’s door. “‘I want to find out what you know about this topic,’” an amused Richard Blue recalled his older brother saying.

Among Jim’s problems, Richard Blue said, was that he couldn’t say no. He regularly accepted lecture engagements across the world, which drew him farther away from filmmaking.

In an interview with Buffalo’s Spree magazine in 1979, he said, “I wish I were in Buffalo more often and I could settle in. I’m over-committed to too many areas and projects.”

One of his unfinished projects perhaps presented his biggest challenge in film and life. In what he began calling the Family Film, Blue interviewed all of his living relatives in preparation to tell the family’s story in film.

His friend and screenwriter Gill Dennis was working with him on the script for the film. Dennis would later go on to a celebrated career in scriptwriting, including for the Oscar-winning Johnny Cash biopic, “Walk the Line.”

“Jim was trying to get away from his family because their lives were fraught,” Dennis said. “He wanted to get distance from it to see it from the outside. If you really look at the lives of his family, these people live heroic lives on the farm.”

If he were still alive, he might still be working on Family Film, said Richard Blue. “James agonized about this film. He couldn’t make it. It may have contributed to his death.”

In June 1980, Richard Blue was working in Indonesia, when a doctor from London called and told him his brother had three weeks to live. A quickly spreading stomach cancer couldn’t be stopped.

Richard collected his brother from the hospital in London. Before they left, the doctor asked Jim if he would talk to a group of medical interns about the experience of receiving the news about his impending death. “An actor to the last, Jim got up in front of the group, talked and took their questions for nearly an hour,” Richard Blue recalled.

Blue flew back to Buffalo, where he was on leave from his teaching post and died June 14 of that year.

In what would be his last interview, and while his cancer advanced, Blue still held out hope that he would get back to filmmaking. An interviewer asked him if the Family Film would ever get made.

“I hope it will, I hope it will. … It’s been a long range thing that we’ve returned to several times and never seemed able to find the spark to make us finish it. It’s complicated. There is a question of too many dreams, too many expectations placed on the film,” Blue said.

When Jim was depressed, he wrote in his diary as therapy, Richard Blue said. One entry struck him. Jim filled an entire page with a strident reminder to get back to what he loved most, “Film, film. film, film, film …”

Jim would get on a plane with Tex-Mex food and a bottle of scotch and show up at

Richard's door. 'That's what attracted me to this article, nice article