In 1892, a twenty dollar gold piece was sewn into the back of a jacket, worn by a gangly youth, en route to San Francisco. A quarter century of drawing pictures on walls and boxes led to this departure. Homer Calvin Davenport of Silverton left the nest of this rural nineteenth century Oregon town bound for the cutthroat world of a daily newspaper’s art department. Raw, self-taught talent, coupled with family connections, helped grease the skids of Davenport’s departure and eventual success.

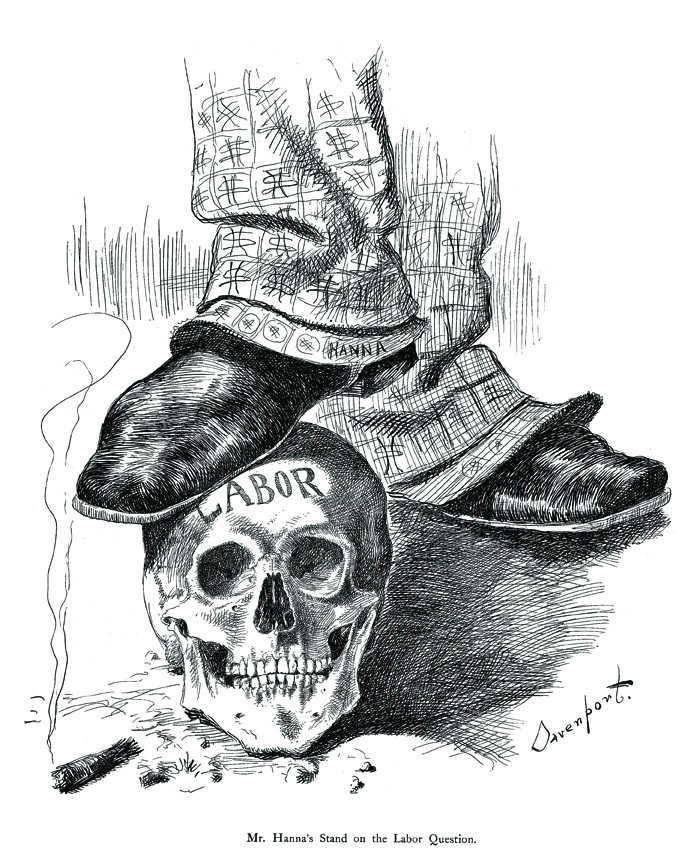

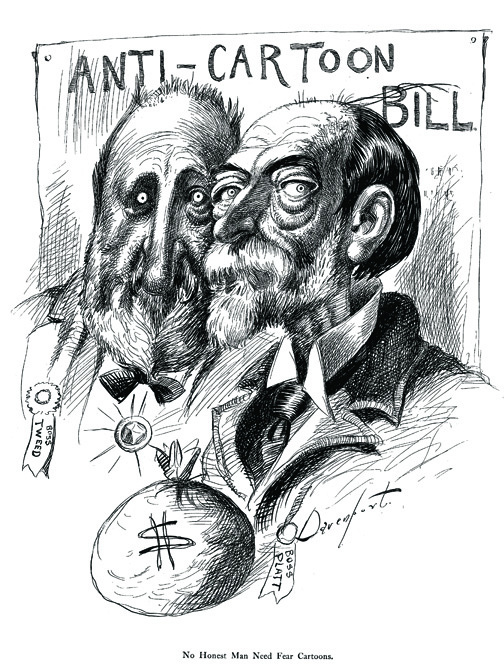

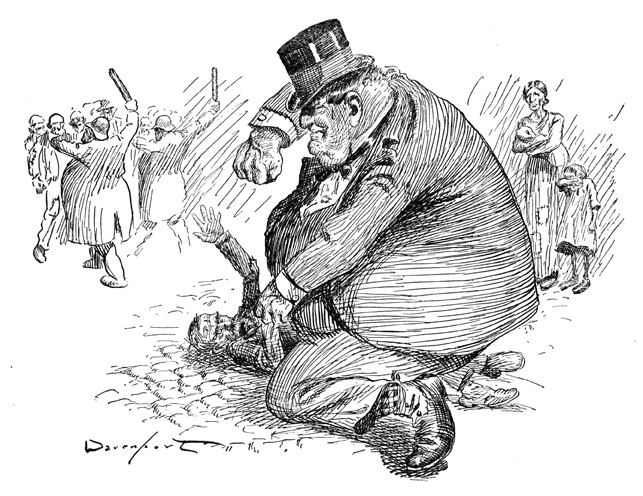

The boy who had learned to draw highly stylized caricatures in the small town of Silverton went on to become the highest paid cartoonist in the world. Homer Davenport redefined the genre of political satire and, strangely, introduced a new blood line of horses that bares his name to this day.

In a biographical sketch written by his father in 1899, pioneer politician Timothy Davenport laid bare the reality—that his son first picked up a pencil at the age of 2 and never stopped drawing. Drawing was so natural, he wrote, that it became second nature to young Homer. His parents, and especially his mother, Florinda Geer Davenport, encouraged these activities. She was a longtime fan of Thomas Nast’s Harper’s Weekly illustrations, and saw in her toddler son the same potential for the same talent. Prior to her death from smallpox, when young Davenport was just 3, she asked her husband on her death bed to encourage their son’s art above all else. And this he did.

Politically, the elder Davenports were of the progressive populist stripe. His mother was an astute observer of human character, and skilled at impersonation. His father was a leading force in the formation of Oregon’s early political scene. He served as a Federal Indian Agent, Marion County surveyor, multiterm state legislator, unsuccessfully ran for U.S. Congress, was Oregon’s first land agent and a prolific social commentator.

Davenport’s world was changing with increasing speed. The idyllic town he knew in his youth succumbed to industrialization as railroad travel came to town. The old Main Street oak, long a symbol of pioneer times, gave way to

visions of newcomers, with higher collars and smaller hats. They brought new ideas of how a modern town should

look, and then unilaterally decided to chop down the old oak. Davenport was determined to move on.

After seeing an example of young Davenport’s drawings, William H. Smith, his father’s cousin and a founding partner

of the Associated Press, secured a letter of introduction to the head of the art department of the San Francisco Examiner. The skills that first attracted Smith to young Davenport were soon lost in the hectic pace of the upstart paper, dubbed “Monarch of the Dailies” by its brash young publisher William Randolph Hearst. The greenhorn artist was assigned to illustrate real estate ads and similar traditional illustration tasks.

Hearst was on an extended tour of Europe when Davenport was eventually let go for his lack of technical skill. An example of Davenport’s work hung on the art department wall as a graphic reminder on how not to illustrate.

Smith intervened again, this time securing Davenport a position at the Chicago Tribune, during the Columbia Exposition—the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893. The artist was assigned to the race track to illustrate horses. It was here he saw his first Arabian horses.

For thousands of years, the Bedouin tribes of Arabia had bred horses for speed, stamina and intelligence. As the European powers expanded, the military recognized that the Arab horse was ideal, especially for a massive light cavalry. As a consequence, the Ottoman Empire, which controlled Arabia for millennia, kept a tight reign on the export of their military horses.

Prior to 1893, the only pedigreed Arabians that came to the United States were gifts by the Sultan of Turkey to President Ulysses S. Grant in 1878. Then in 1893, the Hamidie Society, a group of Turkish business interests, received special permission from the Sultan to display a dozen or so of the best bred Arabians at the Chicago World’s Fair.

Davenport was infatuated with stories of Arabian horses from childhood, so when he first spied the Hamidie horses, he dropped all else and clung to the Arabians. He was easily distracted, and quickly lost his position at the Tribune. Once the fair closed, the Hamidie herd remained in America due to unpaid back rent. Several died in a fire, but most were sold off.

Back in Chicago, life took an unexpected turn when Daisy Moor arrived from San Francisco. Davenport had dated Ms. Moor, a daughter of San Franciscan society. He decided they were not a good match, and he told her so. She had other plans, and went to his cousin Smith to announce that she “was in a family way.”

Based on Daisy’s “greatly exaggerated” testimony, a hasty wedding ceremony was arranged. The newlyweds returned to San Francisco on the private Pullman car of cousin Charles Smith, William’s railroad magnate brother. Davenport found a position at the San Francisco Chronicle. Daisy’s “family way” proved to be otherwise, and a son, Homer Clyde Davenport, wasn’t born until two and a half years later.

The Chronicle gave Davenport more artistic freedom, allowing him to quickly establish himself as a master caricaturist. When Hearst returned from Europe and saw Davenport’s work, he forced his art director to “eat crow” and hire Davenport back, at twice the salary. Hearst quickly made the best use of the Oregonian’s inherent talent. The generous and growing salaries not only kept his young family fed, but fueled his appetite for exotic animals.

Hearst’s 1895 acquisition of the struggling New York Evening Journal brought him the opportunity to go toe to toe with his former mentor, Joseph Pulitzer and his New York World. Hearst sent a telegram to his general manager in San Francisco requesting the immediate transfer of his core team, including Davenport, to New York to get the Journal off and running in true Hearst style. The impact of Davenport’s cartoons in this new market was explosive.

Despite working in New York City and living in New Jersey, Davenport always considered himself an Oregonian. He often signed his name “Homer Davenport, late of Silverton.” He bought one farm in New Jersey, then a larger one, and continued to add stock. Over the years, Davenport kept track of the plight of the Hamidie Arabs from Chicago, biding his time.

In 1903, Davenport left Hearst for the New York American, ostensibly over Hearst’s treatment of President Roosevelt, whom the artist admired. He embarked on a highly successful second career as a lecturer, under the management of Major James Pond, who also handled such dignitaries as Mark Twain and Winston Churchill.

Davenport lectured on the powerful and famous people he had cartooned, peppered with stories from his own life back in Silverton. All the time, he drew cartoons on large sheets of newsprint. These were often auctioned off for various charities and causes.

As his fame grew, the home state beckoned. In 1905, it was Oregon’s turn to host a World’s Fair, and the Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition was it. The organizers, including the Oregonian’s Harvey Scott, wanted to present a cosmopolitan Oregon, and Davenport was personally invited to participate. Off and on during the six-month run, the Davenport family lived on site in a special log cabin. This mini-Davenport farm hosted a wide variety of exotic fowl and an Arabian horse from the Hamidie herd.

Six months in Oregon served Davenport well. He had returned as a hero, and he was in high demand. He made numerous appearances around the state, and entertained crowds on the “Davenport Farm” at the fair. He cut out silhouettes of people with black paper—his skill with the scissors as sharp as his pencil.

Davenport’s increasingly pro-Republican work led directly to a friendship with Teddy Roosevelt and an influential drawing. During the 1904 campaign, a Davenport cartoon was said to have pushed public opinion in Theodore Roosevelt’s favor. “He’s Good Enough for Me!” floated over an image of Uncle Sam with his arm resting firmly on Roosevelt’s shoulder.

Returning back east, Davenport had little trouble bending the ear of a newly re-elected and grateful president, who also happened to be a fellow equestrian. He asked for Roosevelt’s support in importing a small breeding herd of horses from the Syrian desert of the Ottoman Empire. Desert-bred Arabians would be a more logical choice of mount for the U.S. Calvary, Davenport argued, especially in the desert of the American Southwest.

A U.S. State Department letter opened the door to Turkish diplomat Chinkeb Bey of the Ottoman Empire. Bey asked Davenport how many horses hewanted to import. He replied, “Six or eight mares and stallions.” An official trade of importation was issued on the spot to allow Davenport to bring home six or eight mares and stallions.

Davenport had originally planned on going to Arabia alone. A senior partner in a New York law firm, Charles A. Moore, then asked if his son, Charles Jr., could accompany Davenport. Likewise John Henry Thompson, Jr., an acquaintance in the advertising field, asked to tag along.

New England industrialist Peter Bradley financed the mission. Bradley was also a horse breeder and personally bought six of the Hamidie herd, several of which he later sold to Davenport. This initial partnership eventually grew into the present-day Davenport Arabian Conservancy in Winchester, Illinois.

With just two weeks preparation, the trio left New York Harbor on July 5, 1906. By July 19, they were in Constantinople (present-day Istanbul) via Paris and the Orient Express. Once the mission was officially recognized by the Sultan, the group chartered a steamer to Syria.

In the central town of Aleppo, the Americans committed their first cultural faux pas.

Protocol demanded that dignitaries contact the governor of the province prior to arriving. The Americans, however, turned right and followed the horses—soon ending up at the home of the Turkish liaison to the Bedouin tribes, Sheikh Ahmet Hafiz.

Hafiz was so honored that these Americans snubbed the Ottoman governor to meet with him first, he made a gift of two horses to the group, on the spot. When they did meet with Governor Pasha shortly after—not to be outdone, Pasha gave them another mare. Hafiz was a good judge of character, and recognized in Davenport a kindred spirit. Soon the “Oregon Arab” was part of his inner circle.

With Hafiz as escort, Davenport and his companions bought more than two dozen pure-blood and pedigreed Arabian horses from the Bedouins over the next month. The Americans departed the Middle East in September, and arrived back in New York City early October.

Davenport went on to recount the adventure in a series of magazine articles, and then eventually in a best-selling book, My Quest of the Arabian Horse, still in print today.

The breeding program, while soon abandoned by the Army in favor of motorized devices, became quite successful in its own right. To this day, so-called Davenport Arabians are renowned within the Arabian horse community. Indeed, “Mr. Ed,” TV’s talking horse from the 1960s, descended from the mare Wadduda, one of the two Arabians Sheikh Hafiz presented to Davenport in Aleppo.

During his frequent visits back west, Davenport often made a beeline to the pioneer homestead of his grandparents that lay just south of Silverton in the Waldo Hills.

Built in 1851, the Geer farmhouse serves as central hub to the GeerCrest Farm and Historical Society, still maintained by members of the Geer family and others. This educational heritage center and working farm, has a menagerie that includes goats, pigs, chickens and a trio of Davenport Arabians.

A glassed-in frame protects an unpainted section of the ancient siding along the porch, where a sketched figure is kneeling and crying. Davenport, in April 11, 1904, wrote these words above his sketch: “I want to say that from this old porch I see my favorite view of all that the earth affords. It was the favorite of my dear Mother and her parents and of my Father; and why shouldn’t it be the same to me? It’s where my happiest hours have been spent.”

Davenport wrote several letters to his cousin, Burt Geer, making initial arrangements to buy the Geer family farm. He wanted to come back to Oregon, work on a new book of cartoons and raise Arabian horses. A telegram from his former boss changed everything:

“Davvy. Come home. Hearst.”

Davenport decided to return to Hearst’s employ in New York. The following month, an iceberg sunk the RMS Titanic, becoming the subject of Davenport’s final published work. While he was waiting in the rain on the New York docks to interview Titanic survivors, he contracted pneumonia. Hearst hired a team of eight doctors, but they couldn’t save his ailing friend, who died May 2, 1912.

In the end, Hearst arranged for Davenport to indeed return home one last time, and financed an elaborate funeral in Silverton. With its lack of Biblical scripture and spiritualist overtures, the service appeared unorthodox to many of the hundreds in attendance that day. “Not a dry eye in the lot,” was the general consensus as reported in the Oregonian. As Davenport would have said: “It was Silverton in every sense.”

Wonderful article, as usual. The History of Homer is enlightening to say the least. I think every high school should acknowledge him in their curriculum, if they don't already. It's fascinating. Sorry I was slow getting to it. I was checking in on Davenport Days to see how it went this year and came across this. So glad I did.

Cheers! Sue