written by Sig Unander

Kneeling blindfolded on the stone floor of a dungeon in medieval Fort Santiago, the prisoner heard a command: “Bow your head!” A Japanese officer stood above, gripping a gracefully curved sword.

The sharp blade rested on her neck. She had played dramatic parts before, impersonating a glamorous Filipina nightclub owner, fooling clueless enemy officers time and again. But this was no act. In moments her head would be severed with a quick downward stroke.

The daring resistance leader and spy who had eluded capture for two years but now found herself at the mercy of the Emperor’s secret police, was in reality a high school dropout and working mother from Portland, Oregon.

Born Mabel Clara Dela Taste on December 2, 1907 in Michigan, she came west with her mother, Mable, stepfather, Jess, and two sisters, arriving during the greatest economic boom in Portland’s history. Jess, a tall, easygoing Southerner, worked on a ship on the Willamette River. Mable, a stout, no-nonsense Christian Scientist, worked as a midwife and made sure the girls attended Bible class on Sundays.

Clara entered Franklin High School in the autumn of 1922. Tall, pretty and outgoing, she was elected president of the Girl’s League. Classes and student activities didn’t hold her interest, though. After school, she would walk out past the football field and up Mount Tabor to sneak a smoke, look across the city and dream.

Clara’s social options were limited. West Hills girls could borrow their father’s Cadillac and take friends to Hill Villa restaurant or the Multnomah Athletic Club. Clara’s options included hopping a big yellow PRL&P trolley or walking, often to Oaks Park or the Clinton Street Theater to watch Norma Talmadge and other silent film stars on the silver screen.

Dating guys who attended upscale Hill Military Academy or Lincoln High was a long shot; early marriage to a working stiff and a dead-end job in some gritty eastside factory were more likely. Craving adventure, Clara ran away, joining a traveling circus that passed though Portland. She sold tickets to a snake charmer’s show, and when the performer fell ill, she replaced him. The gig was short-lived. When her mother caught up with the show, Clara was escorted back home.

Undaunted, Clara overcame her parents’ objections and was allowed to try out for stock theater. A “natural,” she could sing, dance and act. She worked with the Baker Stock Company, then toured, using several stage names. She later performed with a musical unit in the Far East, ending up in the Philippines.

Manila was a vibrant seaport that retained its Spanish colonial charm. There, Clara met and wed a Filipino merchant mariner and adopted a baby girl, Dian. The hasty marriage didn’t last, though. Unhappy with her domineering husband, she left him.

In the summer of 1941, the Japanese Imperial Army invaded French Indo-China and was preparing to move on Burma, Singapore and the Dutch East Indies. Only the Philippines—the most strategic American outpost in Asia—stood in the way.

That fall, Clara, now calling herself Claire, was performing in a casino. One night, as she sang under soft pastel lights to some American soldiers, she met the love of her life.

John “Phil” Phillips, a tall, handsome, soft-spoken sergeant, was in the audience with his buddies from the 31st Infantry. The men listened as they slaked their thirst with cold beer. As Claire sang “I Don’t Want to Set the World on Fire,” she focused on Phillips. “Our eyes met, held and lingered. The soldier looked at me in the manner that a woman longs to be gazed at earnestly … Ours was a case of true love at first sight,” she wrote in her memoir, Manila Espionage, published in 1947.

Through the fall of 1941, the new couple lived “fleeting, glorious days” in the sundrenched colonial city—dancing, swimming, horseback riding—oblivious to military preparations all around.

Gen. Douglas MacArthur decided not to defend Manila, and instead retreated into rugged Bataan peninsula, across the bay. There, Fil-American forces would hold until relief came from the States. Phil and Claire joined the exodus of soldiers and refugees. The danger didn’t deter Phil from planning a wedding. On Christmas Eve, in a makeshift chapel in the jungle, with the blessings of a village priest, the soldier and the singer became man and wife.

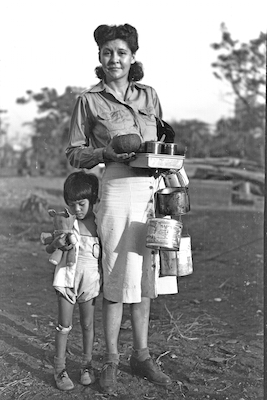

The army, cut off and weakened by disease, was struggling to hold Bataan. Phil told Claire to be brave and hide until he could find her. Dian was smuggled to various hiding places around the region. After they parted, Claire met John Boone, a hard-bitten corporal who proposed a daring plan: form a guerilla outfit to fight the enemy. Boone asked her to go to Manila to establish a source of supplies.

Claire’s resolve stiffened when she saw thousands of prisoners of war shuffle by on the Bataan Death March after Fil-American forces surrendered on April 9, 1942. Columns of exhausted survivors stretched as far as the eye could see. If a man tried to get a drink, a Japanese infantryman executed him with a headshot or bayonet thrust.

Hearing that Phil had been captured and was in Manila, Claire slipped into the occupied city. Forging papers, she created a new identity: Dorothy Fuentes, an Italian-Filipina mestiza. “Dorothy” volunteered as a nurse in Malate Church hospital, connecting with a group that was smuggling food and medicine to American prisoners.

Cabanatuan was the largest prisoner of war camp in the Pacific. Conditions were appalling: meals of rice slop, no sanitation, rampant dysentery and disease. Men laboring under the blazing equatorial sun died like flies. Beatings, torture or execution were common. In this environment even a little food or medicine meant a chance to live.

Claire found work as a hostess at a nightclub catering to Japanese clients. One night she was beaten by a customer who felt that she, a mere woman, had failed to show proper deference. The club’s owner, Ana Fey, stood by and watched.

As her bruises healed, Claire contemplated revenge. Hocking her jewelry, she leased a dance studio and transformed it into a glamorous, upscale nightspot. She hired her boss’ best employees to staff it.

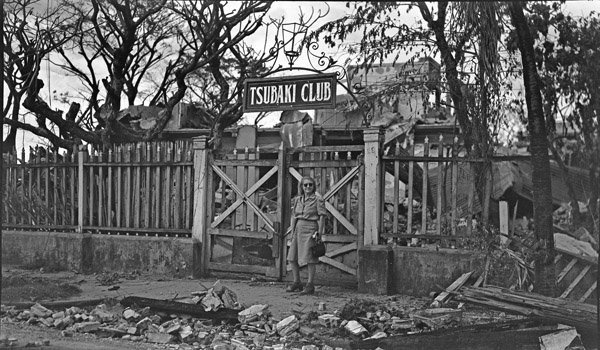

In October, 1942, the exclusive Tsubaki Club opened its doors to the cream of occupation military officers and civilians—Ana Fey’s best customers. Receiving them in a stunning white halter-necked gown, Claire bowed and spread her arms in a balletic pose. Konban- wa, she cooed.

The club featured a floor show of Asian dances, folk songs and sultry “torch” numbers, sung by Claire herself. There was a Siamese Temple dance inspired by Hedy Lamarr, a Siva Siva dance and a spectacular flaming torch routine. Guests were attended by beautiful hostesses and white-jacketed waiters serving tropical drinks.

The club was a hit. Its patrons were delighted with the entertainment and atmosphere. The outrageous prices they paid were used to buy food and medicine on the black market that were subsequently smuggled into prisons and to Boone’s guerrillas.

Claire’s ablest employee was Fely Corcuera, a willowy Filipina who spoke Japanese. Dressed in a kimono, Corcuera would sing traditional Nipponese songs to homesick officers. Then she would sit, light their cigarettes, stroke their hair and gently encourage them to pour their hearts out. Information so gained was sent to MacArthur’s headquarters in Australia.

Soon after the club opened, word came that Phil had died in Cabanatuan. The news devastated Claire. Only after receiving a plea from a chaplain to remember others who were dying by the hundreds was she able to continue.

The Manila underground was a diverse group of expatriates, socialites, priests, students and street vendors. All used cover names. Claire, for her quirky habit of carrying notes in her bra, became “High Pockets.” Their slangy code had a culinary twist: “Cookies” meant contraband to be “baked” (smuggled) when the “recipe” was ready. If intelligence was useful, the reply was: “Beans very good, send more.”

To get aid into Cabanatuan, runners took goods by train to the nearby town. There, an innocent-faced Filipina street peddler sold bags of fruit to prisoners who went into town under guard. They paid a few centavos for a bag with hundreds of pesos hidden in the bottom. Bananas were stuffed with messages or medicine. Inside, contraband was distributed to the neediest. One grateful prisoner sent Claire a note: “You deserve more gold medals than all of us in here together.”

The most dangerous adversary was Colonel Nagahama, head of the Kempeitai field office. An Imperial War College graduate, the balding, bespectacled officer was brilliant and ruthless. When not enjoying floor shows at the club, Nagahama ran an obsessive hunt for spies, including the elusive “High Pockets.”

One evening the colonel was in the club with staff officers and invited Claire to his table. Amid banter and toasts, he bragged about executing an American officer, demonstrating how he shot the man as he kneeled, blowing his brains out. Claire pretended to laugh, then excused herself and was violently ill.

The strain of running a business and coordinating operations took a toll. Claire contracted tetanus and barely pulled through. She resumed her activities but the net was closing fast. In May, 1944, four armed Kempeitai raided the club and took her.

Five months of interrogations in the dank cell blocks of Fort Santiago followed. The treatment included savage beatings and worse. Claire was strapped to a board and water forced down her throat until she passed out. She was “revived” with lit cigarettes pressed into her skin. In another session, a nail was driven under a fingernail until she fainted.

Late one night, Claire was questioned about smuggling into Cabanatuan. She denied it, even after being beaten bloody. She was dragged into a torture chamber and ordered to talk. “I felt the cold, sharp steel of a beheading sword laid tentatively against my neck. “‘This is it,’ I thought … and then mercifully blacked out.”

Incredibly, the executioner failed to deliver the fatal stroke. Had Claire called her captors’ bluff, or had they, impressed by her bravery, relented? It was likely a ruse to get her to talk, a terrifying deception. She was then given a court-martial. Charges were read before a tribunal without testimony and a “guilty” verdict pronounced.

Before dawn, Claire and another prisoner were shoved into a car and driven out by the old Chinese Cemetery in Manila. Convinced she was about to die, she invoked a higher power: “… My thoughts jumped to my family in the States. Then my beloved Phil … As I prayed, a profound feeling of peace and quiet descended on me …”

The car stopped. Claire looked up. “A large sign met my eyes … Women’s Correctional Institution.” Inside its forbidding walls, a guard read the sentence: twelve years hard labor. Hearing it, she collapsed. This story was sourced from Manila Espionage.

The regimen in the institution was forced labor on a starvation diet. Claire, weighing 85 pounds, began to doubt whether she would see the liberation she believed was coming. As the U.S. Army advanced on Manila, word came that soldiers were executing prisoners before Americans could reach them. Early on February 10, 1945, a warning sounded. Claire dived under her bed and huddled there.

Claire and Dian reunited and sailed back to Portland, where Claire joyously reunited with her family. Her story appeared in Reader’s Digest, and she sent publisher Peter Binford a manuscript. He rejected it as “the best fiction I’ve read.” Then, after seeing her clippings, he agreed to publish it.

Claire’s heroism had not gone unnoticed. General MacArthur recommended a decoration and, in 1948 at Fort Lewis, she was welcomed by Gen. Mark Clark and awarded the Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor for “inspiring bravery and devotion to the cause of freedom.”

Soon afterward, Claire signed with United Artists for a film, with her role played by movie star Anne Dvorak. In Hollywood, she was called to NBC studios for an interview. Instead, host Ralph Edwards, U.N. Secretary Gen. Carlos Romulo, Gen. Clark and others greeted the surprised guest for a taping of the show “This Is Your Life.” Then Edwards flew to Portland and presented Claire with a new home and car. Gov. Douglas McKay and Mayor Dorothy McCullough Lee praised her before 2,500 well-wishers.

Claire busied herself working, remodeling apartments and taking speaking engagements. The high-profile heroine found herself living a double life: public personality and working mother by day, then drinking after hours to quell her nightmares. The post-traumatic stress severely affected her health. She fell ill and was admitted to Portland Sanitarium. Despite doctors’ best efforts, she died on May 22, 1960. She was 52.

Today no plaque or monument honoring Claire Phillips exists in Oregon. Only in the Philippines is she memorialized. In the United States Embassy in Manila, a life-sized portrait of “High Pockets,” faithfully rendered in oil, adorns the Claire Phillips Room, a meeting place for visiting dignitaries. Fittingly, it adjoins the room where generals were convicted of war crimes for atrocities in Manila.

My Grandmother Ruth Green was Claire Aunt . I remember the stories of Claire when my Father come home from WWII

just finished the book

cant stop thinking about her

brings tears to my eyes

what ever happened to her daughter dian?

mihael

Thank you for getting my great aunt some local recognition.

Wow. An amazing story about my great aunt that needs to be told and remembered. Thanks, Sig.

Amazing story about a very brave woman.