written by Anna Bird | photo by Kendrick Moholt

Alvin M. Josephy Jr. would take off on horseback from his quaint Joseph ranch and ride up the spine of the east moraine. He would take his youngest daughter, Katherine, and they would ride along the ridge, only to stop when they reached a good viewpoint. They didn’t have to go far. The moraine surrounds Wallowa Lake, a deep blue glacially carved lake in the shadow of the towering Wallowa Mountains. The town of Joseph forms a small cluster of homes and businesses to the north, and beyond the town is a patchwork of farmland. To the east is the Imnaha River Canyon, where Josephy would take his family on drives during their summers at the ranch.

photo by Kendrick Moholt

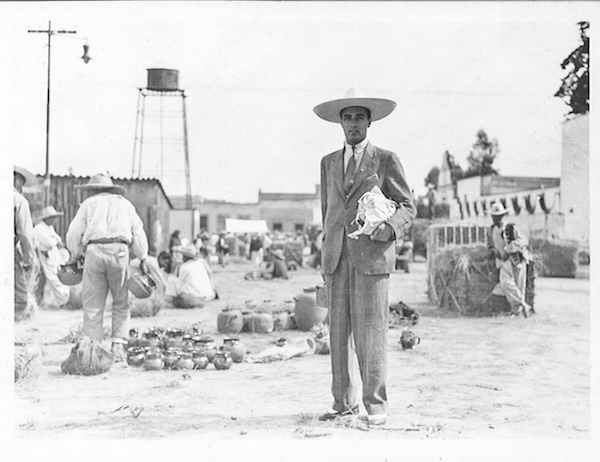

By the time he first visited Joseph in 1955, middle-aged Josephy had dropped out of Harvard, worked as a screenwriter in Hollywood, at the age of 22 interviewed Soviet Marxist revolutionary Leon Trotsky and Mexico’s president Lazaro Cárdenas del Rio, worked for the New York Herald Tribune, fought in the South Pacific during WWII, recorded the landing at Guam, landed a job at TIME magazine and had four kids from two marriages.

No matter how storied his life had been until that point, his daughter believes Josephy was the most content sitting atop his horse, looking out over the Wallowa Valley, though he wasn’t much of a horseman.

Born in 1915 in New York City and raised on stories of brave men forging west—the explorations of Lewis and Clark, pioneers on the Oregon Trail—Josephy dreamt of Oregon his whole life. As he grew up, he would come to see the stories that colored his childhood had real places in history. When he finally ventured to the Northwest in the early 1950s, he found the people who lived those histories.

It was one particular story that led him to Oregon, and eventually his ranch in Joseph. It was an Old West drama of betrayal, greed and injustice. While on assignment in Idaho for TIME, he learned the story of the Nez Perce War, which is largely considered the “last Indian war.” His interest grew when he discovered that this story was largely untold.

What he found ended up being the motivation for the last five decades of his career, until his death in 2005. He would become the leading non-Native writer on American Indian issues, a prominent historian and author, a political advisor on federal Indian policy during the Nixon administration and the founding chairman of the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian.

The Journalist

photo courtesy of Alvin M. and Betty Josephy Library of Western History and Culture

Josephy’s only son, Alvin III, or Al, said that first and foremost, his dad was a journalist. He got his first taste for the profession as a high school student at Horace Mann School for Boys, a private college preparatory school in New York. He wrote for the Horace Mann Record, and interviewed famous writers such as H.L. Mencken—a family friend—the French biographer André Maurois and British playwright Donald Ogden Stewart.

He scraped through two years of Harvard during the Depression, but couldn’t afford to finish. Instead, he went to Hollywood for a job as a junior screenwriter at MGM. He found that he was more moved by real drama than moving pictures. “I had rubbed shoulders with history, and I was far more interested in it than in the make-believe world of MGM…” Josephy wrote in his memoir, A Walk Toward Oregon.

He returned to New York and got a job working for the New York Herald Tribune in 1937, after an unfulfilling year-long stint on Wall Street. He met well-known importer of Mexican goods Fred Leighton at a party. Leighton told Josephy he should go to Mexico as a foreign correspondent for the Tribune. Josephy persuaded the paper to give him credentials and then paid his own way. At the age of 22, he was on a quest to interview Leon Trotsky, the Russian Marxist revolutionary living in exile in Mexico City, and Mexican President Lázaro Cárdenas.

In the home of Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo, where Trotsky was then residing, Trotsky and Josephy discussed the USSR, the Red Army, the Franco fascists in Spain and the possibility of Stalin joining Western democracies in a united front against Hitler. The interview resulted in a story for the Tribune and a longer feature in the short-lived periodical Ken.

The Veteran

photo courtesy of Alvin M. and Betty Josephy Library of Western History and Culture

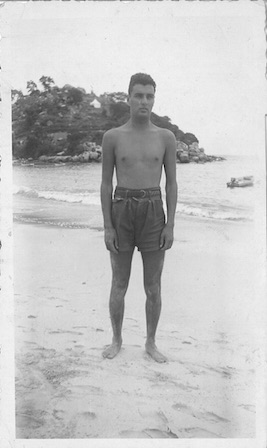

During the war, Josephy worked for a government radio bureau before enrolling in the Marine Corps as a combat correspondent. He deployed to the Solomon Islands in the South Pacific, in a division under General Douglas MacArthur. Having worked in radio, Josephy was told to pack recording equipment along with his typewriter.

On June 21, 1944, Josephy’s division was the third wave of attacks on Guam. He was ordered to fight as a marine while simultaneously recording the landing operation and describing the invasion for American network broadcasts. This feat had never been done before.

“At 6:00 a.m., speaking into a hand microphone covered with a condom to protect it from seawater and connected by forty feet of wire to the recording machine…I began to make my recording, describing the scene as we went over the side of our transport and down into little landing boats,” Josephy recalled in his memoir. As they waded to shore, they came under machine gun fire from hills behind the beach. “I just kept talking into the hand microphone, telling what I was doing, what I was seeing, and what I was thinking, and soon, amid the smoke and the noise of diving airplanes and the naval gunfire, I became so preoccupied with talking that I stopped being afraid and grew numb to the reality of what was happening.”

The Historian

photo courtesy of Alvin M. and Betty Josephy Library of Western History and Culture

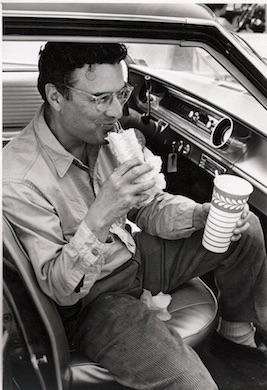

Josephy began working for TIME in 1951 under legendary magazine magnate Henry Luce. Josephy was the associate editor for the monthly color photo section and traveled around the world coordinating stories with writers and photographers. The stories ranged from rare photos of the U.S. Coast Guardsmen on D-Day to marine biologists in the Atlantic, from Tashkent in the Uzbekistan Republic to the Ivory Coast’s Agneby River Delta.

Luce sent Josephy to Idaho around 1952 on assignment. From the airplane, Josephy understood why Luce was impressed with Idaho. The Snake River canyon, the rugged desert country and the Sawtooth Mountains were the wild lands of his childhood stories.

While touring the state, Josephy’s guides took him to the Nez Perce Indian Reservation near Lewiston. Leaving the reservation, his guides asked if he had ever heard about the Nez Perce. He had not. “Well, they once fought a war against the United States and beat four American armies,” Josephy recalled his tour guide telling him.

Josephy was intrigued, and before he left Lewiston he grabbed local books and pamphlets on the topic to investigate. What he found was a story told from one perspective with no depth of character, a multitude of pervasive stereotypes and little else. “Moreover,” Josephy wrote, “so little was included about the details of the forced removal of the Indians from their lands that it was hard to understand what had possessed the government to commit such an injustice.” As he returned to New York, the story of the Nez Perce stayed with him.

Luce was staunchly anti-Indian, so an article in TIME on that topic wasn’t yet a possibility. “What I decided to do was to write an interracial book from the point of view of somebody standing on the moon,” Josephy wrote in A Walk Toward Oregon. The person on the moon would observe the homeland of the Nez Perce and the evolution of European settlers gradually surrounding the Nez Perce before taking their land. He began the twelve-year project of writing The Nez Perce Indians and the Opening of the Northwest—a dense, 650-page history of the Northwest from the time of Lewis and Clark’s exploration to the Nez Perce surrender in 1877, published in 1965.

He took a short break in 1955 to write an article on the naming of the Nez Perce, and again in 1958 to write an article on Chief Joseph for American Heritage magazine. The latter inspired a longer interruption to publish his first book on the subject, The Patriot Chiefs, in 1961, in which he integrated the biographies of prominent chiefs across the country. Rich Wandschneider, whom Josephy befriended in Joseph in the ’70s, remembers Josephy saying, “There were a lot of good Indians who tried to accommodate whites, I skipped them.”

He went on to write and edit more than a dozen books about various American Indian histories and countless academic and journalistic articles. Though he never graduated from college, he was a meticulous researcher and arguably a better historian than many of those with college degrees. “When you say meticulous, he deeply researched primary sources and cited ruthlessly,” said his son, Al. “My dad would drive to some library way in (the middle of nowhere) Montana to go to some little local library and little local museum,” in search for primary sources.

What set Josephy apart from historians before him was not limited to his thorough research or his meticulous practice of citing sources. He sought oral histories from the people who were there.

The Listener

photo courtesy of Alvin M. and Betty Josephy Library of Western History and Culture

Bands of the Nez Perce, before and after the war, were split up between reservations in Lapwai, Idaho and Colville, Washington. He spent time at each reservation, as well as the Umatilla Reservation outside Pendleton. He made friends with those he encountered and gained their trust through his genuine curiosity, his humility and his background as a veteran.

“I think Alvin was a humble man…and he cared very deeply about what he was doing,” said Bobbie Conner, director of the Tamástslikt Cultural Institute in Pendleton who is Cayuse and Nez Perce. “He was genuinely intrigued by his subject-matter. His personality was a plus for him doing that research in Indian country, but I also think that once they realized that he had a combat history, too, they were brothers.”

Conner’s grandfather, Gilbert, was a grandson of Ollokot—one of Old Chief Joseph’s sons. Her grandfather was also a tribal interpreter, worked with data collection projects and was well versed in his family’s genealogy. Ultimately this helped Josephy make more connections between the Nez Perce, Cayuse, Umatilla and Walla Walla tribes.

The story of the Nez Perce War was one that her people always knew, but rarely talked about. She said they live to honor their ancestors and those who sacrificed for their freedom, but the story is too heartbreaking to dwell on. Josephy knew that if this story wasn’t told on the East Coast, it wouldn’t make it into the American conscience.

“It was brought out into the open by someone who was well regarded, someone who was credible,” Conner said. “Someone could have done a much worse job and done us a great disservice, but he didn’t. We are fortunate that he not only chose to write about this history, but we were fortunate that he was compelled to do such a magnificent job.”

To Conner, Josephy’s books are a tremendous contribution to American Indian history. She believes his political impact, however, was even greater. In 1969, Josephy served as an advisor on federal Indian policy to Secretary of Interior Stewart Udall. He wrote a report for President Nixon about the Indian termination policy, which led Nixon to enact the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act in 1975, a policy that greatly empowered tribal sovereignty.

The Legacy

photo by Kendrick Moholt

In 1961, Josephy brought his family—his daughter Diane from his first marriage, his wife, Betty, and their three kids, Allison, Al and Katherine—from their home in Greenwich, Connecticut to Joseph for the summer. In 1963, they bought their ranch just outside of Joseph—a modest house and a small cabin, surrounded by willows, aspens and cottonwood trees, with a large pond where the family would swim. Josephy would do research for his books and write in the small cabin, surrounded by floor to ceiling bookshelves. A Nez Perce friend named the ranch Palojami, which means “beautiful land,” and the Josephys spent every summer there for almost forty years.

Josephy made friends with locals, even though he was “probably (considered) an East-Coast egghead,” joked Wandschneider. The two met in the early 1970s when Wandschneider opened The Bookloft in the neighboring town of Enterprise. Josephy was a regular customer. “Betty would drop him off at the bookstore and say, ‘Take care of him for a while, would ya? I’m going to go visit a friend,’” Wandschneider recalled. The two often talked about local writers, which led them, in 1988, to start Fishtrap—a Northwest writer’s group in Wallowa County. Josephy had a huge impact on Wandschneider, who considered him a dear friend and mentor.

Josephy retired in 1979 but went on to write more books and build out his legacy. He helped start the original Chief Joseph Summer Day Camp in Joseph, and he and Betty, along with other local families, hosted Indian kids who came for the camp. In the early 1990s, he was the founding chairman of the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian. He told his own story with his memoir A Walk Toward Oregon in 2000, at the age of 85, complete with fascinating details of his life—footnotes included.

He died in 2005 at almost 91 years old, and his last book was published shortly after—Lewis and Clark Through Indian Eyes, an anthology he edited from the perspective of local Indians. Along with Vine Deloria, Jr. and N. Scott Momaday, Bobbie Conner wrote a chapter titled, “Our People Have Always Been Here.”

After his death, Josephy’s daughters called Wandschneider to come to Greenwich and collect whatever books he wanted from Josephy’s library. Al estimated he probably had 5,000 books, or more, at the end. The books bestowed to Wandschneider were the foundation for Wandschneider to start the Alvin M. and Betty Josephy Library of Western History and Culture located in the Josephy Center for Arts and Culture in Joseph. The center was named after Josephy and opened in 2012. The center has hosted American Indian artist exhibits, celebrations and gatherings each year since its founding.

This summer, the center celebrated Alvin M. Josephy Jr.’s centenary, along with the fiftieth anniversary of the Nez Perce National Historical Parks.

In the end, the power of stories compelled the young New Yorker to valor and exploration, and to the West, where he used his gift to advocate for America’s first storytellers.

Alvin and bis wife Betty are some of my favorite people. I met them first as a kid – my best friend lived at the bottom of their hill. And I went to Summer Seminars as a kid. As an adult, I had the pleasure of finally getting to know Alvin and Betty as Pappy and Grammy to a little boy I helped babysit – one of their youngest grandsons. The article is a great tribute to Pappy.

We’re really glad the article reflects your experience Gin! These are the kind of stories we live for!

I was fascinated by this article, a perceptive vignette of Mr. Josephy's interests and work, and the impact he had on people, history, and policy. What a legacy he created, and I've only now come to appreciate more fully. Now I want to reread his books, with a more mature perception than when I first found some of his writings when I was a college student. The contributions of Mr. Josephy are even more significant when we consider that Native American history is still being written, as policies change in this jumbled American political landscape.

Fantastic article, well written, great pacing, and a compelling topic. Perfectly done.

We’re glad you like it Bill!

Excellent article. It was an honor to grow up spending my summers on the pond with the Josephy family! I hold these memories near and dear and will never forget the day Alvin corrected my poor grammar. 🙂 He and Betty were wonderful spirits.

How cool that you experienced Oregon history first hand, Dani!

Interesting article Anna. Thank you for writing it. Alvin Josephy once visited my classroom in Joseph. I had invited him to talk about writing and Nez Perce history.

Glad you captured so many interesting aspects of his life.

How cool to have met him in person Lori!

Thank you for this superb article about a wonderful and talented man who thankfully has touched so many of our hearts.

james

I had a speech class in high school. My first speech I gave was on the Nez Perce war. I had read Nez Perce and the opening of the Northwest. This sparked my interest in Oregon history which led to my being a total American history nut. Thank you Mr Josephy.

Very Nice Anna!

Glad you like the article Kendrick!