After bulldozers, highways and development brought down Portland’s historic cultural hub of the Black community, an innovative path forward emerges

Written by Fiona Max

On a Friday evening in the ’60s, locals of Northeast Portland’s Albina district could be found in the Hill Block building, an iconic, domed building on the corner of Williams and Russell Street. At the time, the place was home to the Cotton Club, a jazz club which had quickly gained popularity under owner Paul Knauls. Knauls had worked his way into the scene in Spokane, Washington, at the Davenport Hotel, and had gone to Portland in search of a venue of his own. He bought the rundown Cotton Club in 1963, and brought it back to life. Its fall, Knauls said, would come in 1968, after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., as tensions between the Black and white community ran high.

“People came to the club because they knew they were going to be treated right, they knew they were going to be safe … and they knew they were going to be offered a drink,” said Knauls, dubbed the honorary mayor of Northeast Portland. As the club doors swung open, the sound of some of America’s biggest names in jazz, including Etta James, The Whisperers, Sunday’s Child, Duke Ellington and Mel Brown, spilled into the night. Knauls greeted folks at the door with a broad smile. Dancers, swayers and drinkers filled the place until closing time. The Cotton Club epitomized the Albina district—bustling, beautiful and black-owned. All around it, however, the bulldozing had already begun.

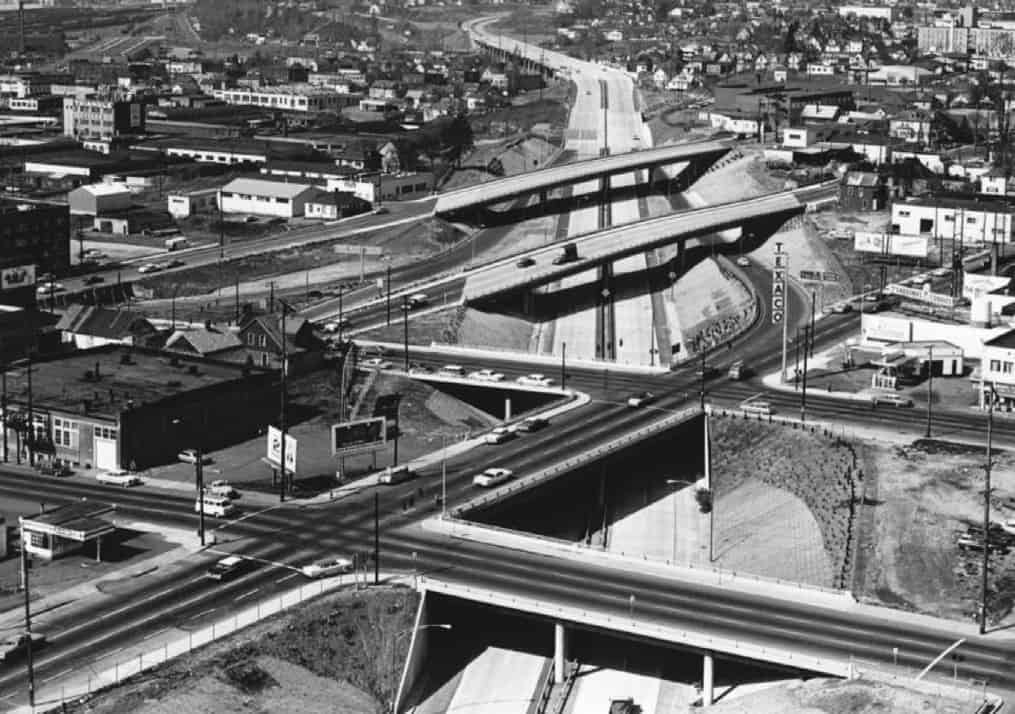

By 1951, the Oregon Department of Transportation had leveled an estimated eighty Albina homes along the Willamette River for the construction of I-99. Eleven years later, ODOT demolished a strip of buildings through the center of Albina to build the I-5 freeway. At the time, Legacy Emanuel Medical Center, originally called Emanuel Hospital, was making plans with the Portland Development Commission to build a new hospital. The hospital’s consulting firm proposed buying the 1.7-acre lot with the Hill Block building, but in 1971, Portland’s City Council adopted the Emanuel Hospital Urban Renewal Project, making way for demolitions that continued for the next two years. By then, the Hill Block building was home to a pharmacy, several restaurants, a laundromat and Knauls’ cocktail bar, Pauls.

“That’s where everybody would meet on Sunday after church, and you could see everybody that you knew,” said Knauls. “That was the place to be.”

The Emanuel Displaced Persons Association formed to protest the demolitions and demand compensation for the homeowners and businesses on the lot, but not before the city displaced 171 households–74 percent of which were Black–and destroyed thirty businesses. Knauls said he was never compensated for the loss of the cocktail bar.

Today, a network of Black-led nonprofits are reimagining the neighborhood with their own urban renewal projects. At the forefront of the revitalization is the Black-led nonprofit Albina Vision Trust, which brings together property owners, public partners and investors committed to bringing Black wealth and joy back to Albina and its surroundings.

In July, Albina Vision Trust hosted a virtual community workshop. Portland NAACP president Sharon Gary-Smith kicked off the meeting, saying, “What I love is we started with a hustle. Now we’re talking about cultivating and rooting and generational joy.” Gary-Smith was referring to the Vision Trust’s Community Investment Plan. Othello Meadows, who leads the investment plan’s community engagement efforts, said during the community workshop, “I say this lovingly … communities are fickle. We knew we had to come out of the ground with a big enough splash to give the community confidence that there was momentum and more to come.”

That splash is a twenty-year construction that stretches north to south from the Steel Bridge to the Broadway Bridge and east to-west from the banks of the Willamette to I-5. A close-knit neighborhood will flourish with affordable and multi-generational housing. Green spaces and parks will weave through the neighborhoods, offering space for family and community gatherings. The east bank of the Willamette River will be transformed from an industrial wasteland to a rich swathe of parks and gardens which pay tribute to iconic Black Portlanders. Albina’s original downtown section will be lined with trees and alive with Black-owned restaurants and shops. A network of community centers, or “hubs,” will enrich the area.

“They are business incubators, they focus on food, adult and youth education, health and wellness and art,” said Josh Shelton of El Dorado Inc., an urban design and architecture firm for the investment plan. Green rooftops on the district’s highrises are key features. “For the first time, everyone living here would have access to that height, to turn 360 degrees and realize the views of Mount St. Helens and East Portland,” Shelton said.

Starting dates for the construction of parks, greenways and affordable housing would be set by the end of September, according to the plan. “As much as we want this to be a sprint, we have to take our time and do it right,” Meadows said. “This model shows an ecosystem, an economy all unto itself … We’re not just shooting for quick solutions and programs.” Regulating housing prices so that the neighborhood stays affordable for locals is another issue which the community investment team is exploring, according to Yohannes. Engaging and prioritizing Black-owned lending institutions and construction companies is another key element of the plan.

“That closed loop will create wealth that is intergenerational,’’ said Mike Wilkerson, senior economist for the Vision Trust. “That is the difference between what you would see in a typical project where money comes in and goes out of a project and the community is no better off. This is about growing those community resources for the benefit of all those future generations.”

The model prioritizes healing the Black community and fulfilling its needs. It strives to avert conflicts which have arisen from previous projects with ODOT. For years, Albina Vision Trust was part of the executive steering committee working with ODOT to build highway covers—concrete overpasses reconnecting streets bisected by I-5. In June, AVT withdrew from the committee, believing ODOT’s plans fall short of the restorative justice Northeast Portland needed.

Bryson Davis is a member of the Executive Steering Committee (ESC) for the Rose Quarter project. The committee was formed so local organizations and community members could advise and collaborate on the I-5 design. “The cover was effectively a big park. It was not going to fully connect the neighborhood, and there were doubts about how much you could even build on top of the covers,” said Davis, a lawyer. “Many felt it would fail to actually serve the community and provide economic benefits.” The plan for the covers continues to be a source of contention among representatives of the city, the community and ODOT.

After the Vision Trust withdrew, ODOT created the Historic Albina Advisory Board to ensure the neighborhood would have representation in the project. Discussion surrounding the feasibility of covers and the efficacy of highway expansion will continue into September and could delay renovation of the highway for two more years. In anticipation of this, the Vision Trust’s community investment plan does not hinge on a specific outcome for I-5.

That closed loop will create wealth that is intergenerational. That is the difference between what you would see in a typical project where money comes in and goes out of a project and the community is no better off. This is about growing those community resources for the benefit of all those future generations.”

— Mike Wilkerson, senior economist for Albina Vision Trust

“Regardless, we’re not going to be deterred from our plan to develop the neighborhood in line with the values of [the community investment plan],” said Winta Yohannes, executive director of the Albina Vision Trust. “We wanted to allow ourselves to dream without constraint on what’s possible and then have a grassroots movement around what can be.”

To move the project forward, Gov. Kate Brown in August announced her support for a proposal that would include a highway cap designed to support three-story buildings. This time, Yohannes says, the proposal is in line with the values of the Community Investment Plan.

At the same time, smaller projects within the Albina community are shifting the narrative and serving as a model for change on a larger scale. The Vision Trust just started their first housing project—turning a parking lot into affordable apartments and a theater. On the other side of I-5, the two entities that once clashed over the Hill Block building partnered in 2017 to begin restoring the 1.7-acre lot, which was left empty after the structure was moved to Dawson Park, in the Eliot neighborhood.

The shift in focus to social and racial equity was reflected in the Portland Development Commission’s decision to change its name to Prosper Portland in 2017. “A name change doesn’t mean anything unless there is action that goes with it, so we’ve really tried to lean into it ever since,” said Shawn Ulman, communication manager for Prosper Portland.

Legacy Emanuel Medical Center shares that perspective. “We, as an organization, had an obligation to recognize the role that Emanuel Health played in the destruction of a Black neighborhood,” said Brian Terrett, communications director for Legacy Emanuel, which is part of the Legacy Health System. “But in one of our meetings, someone pointed out that as long as Prosper Portland, Legacy Health and the city are deciding what to do with the land, the Black community would not get behind it, and they were right.”

The partners worked with the Albina community to form the Williams & Russell Project Working Group, a committee nominated by the community to lead the project. Since then, the group has morphed into the Williams & Russell Community Development Corporation, or CDC. Through community events and meetings, the CDC determined that the biggest demand for the lot was education and workforce training, affordable and rental housing and community and business spaces. The CDC recently partnered with several local firms including Adre, a woman- and minority-owned development company, and Cola Construction—the largest Black-owned construction firm in the Northwest—to bring the blueprints to life.

Plans for the lot include twenty-two townhouse units, affordable apartments, a plaza, garden and communal offices. “We have demonstrated a pathway to bring property back to the community,” said Justice Rajee, CDC co-chair. “The structure used here may not be the best fit for all situations, but the core principle of placing the decision in the hands of the community is a transferable principle.”

The Albina neighborhood is a canvas for restorative justice, but by no means a blank one. The work of the Albina Vision Trust, the Williams & Russell project and other partners is poised to lay the foundations for Black healing, progress and celebration. A detail of the Community Investment Plan foreshadows that—a garden on the waterfront which may be named after Paul Knauls. It’s a place where, one day, the sound of jazz may fill the air in Albina again, resurrecting it for a new generation.