written by Sarah Max, Stacey Wilson, and Holly Grigg-Spall

this article was originally published October 1, 2009. It’s been recovered from our archives for your interest.

In our search for Oregon’s intriguing candidates, 1859 queried dozens of institutions from arts to agriculture and from vintners to venture finance. We fielded nearly a hundred worthy suggestions and narrowed the list to these 16. We then deployed three writers and a team of photographers led by Joni Kabana to tell the story of these fascinating people.

Storm Large, 40 Singer, actress, Portland: Six Feet Tall and Eight Miles Wild

Why: The seductive, provocative writer-singer-thespian has proven that you don’t have to live in L.A. to be a star. (And yes, that’s her real name.)

To call Storm Large a “performer” is a little like saying the Cascades got a “a touch of snow” last winter. Portland’s most provocative chanteuse, the erstwhile reality-show contender (2006’s “Rockstar Supernova”) became the Rose City’s hottest theater ticket in 2009 with her sold-out one-woman show “Crazy Enough,” which ran for nearly five months. It was the musical-drama equivalent of an emotional autopsy; the chronicle of growing up a loudmouth, crazy, and too-tall girl (who, someday, would grow up to have a certain body part that’s “Eight miles wide”). Portland’s love for Large is given back in double time. “It’s such a lush, fertile city for body, mind and soul, it was natural for me to put down roots here eight years ago,” says the Massachusetts native. “As big as my mouth is, I could never express my gratitude sufficiently. This place not only gave me permission to be my big, freaky self, but also gave me a home.”

Institutional Memory Mike Keele, 56 Asian elephant expert, Portland

Why: The Oregon Zoo’s resident elephant guru has made our institution a giant by raising the awareness of the struggles of elephant survival

If you visited the Oregon Zoo in the last year, you likely took in the precious site that is Samudra, or “Sam.” The baby elephant was born August 2008 and, like many before him, was a massive hit among zoo-goers who can thank a humble fellow named Mike Keele for the 1,500-pound bundle of joy. Throughout much of his 38-year tenure at the zoo, Keele has been the chief architect of the Association of American Zoo and Aquarium’s Species Survival Plan for North America, a program established in 1985 to breed viable elephants in hopes that they can continue to inspire conservation action for generations to come. Keele couldn’t be more proud. “I’m a fourth-generation Oregonian who turned nine the day before Packy was born in 1962,” says Keele, now the interim zoo director. “It feels like fate for me to be able to do this job.”

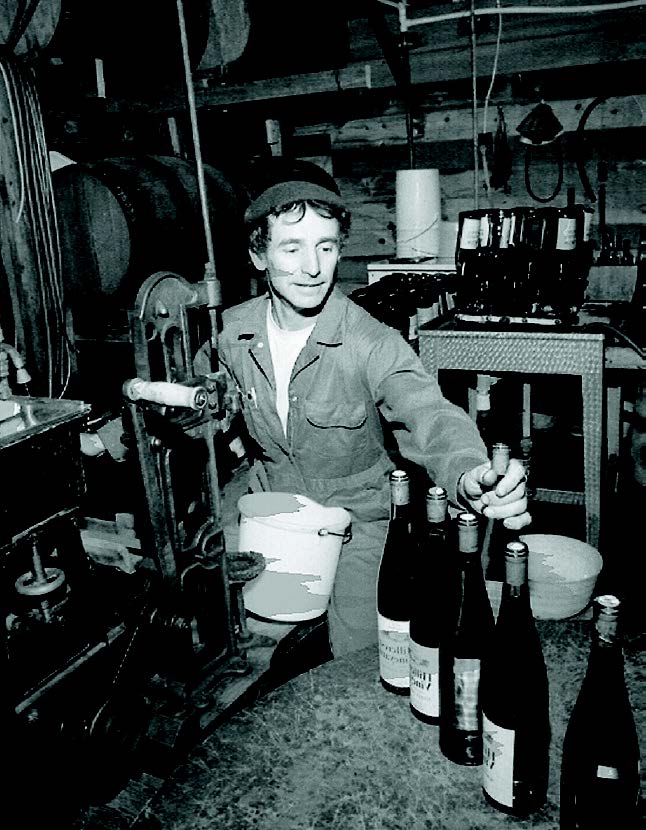

Father Wine: Richard Sommer (1929-2009) Wine maker, Roseburg

In 1961, Richard Sommer, the son of a chemist and microbiologist, pioneered the Oregon wine industry after planting European-style grapes just west of Roseburg. After his professors at U.C. Berkeley derided the idea of growing wine grapes in southern Oregon, Sommer moved to the Umpqua Valley, made Rieslings and Pinot noirs and established HillCrest Vineyards, the seed for today’s burgeoning wine-growing region. “He was always trying something new, something innovative. He had a brilliant mind, but it wasn’t always logical or mainstream.” says Sommer’s sister, Susanne Krieg.

Terrebonne Trailblazers The McIntosh family Farmers, Terrebonne

Mike McIntosh, 46, believes he was born at least 100 years too late. On his farm in Terrebonne, he has a thresher and a sleigh and three wagons all dating back to the late 1800s. These threshers aren’t just decorative antiques, they are what the McIntoshes use to harvest their hay. And the restored 19th century wagons are functional “memory makers” along the Oregon Trail.

For a decade, McIntosh and his wife, Joanna, have taken their three children, Janelle, 16, Jacob, 14 and James, 11, back in history on horse-drawn wagon trips on sections of the Oregon Trail as part of a 40-wagon exhibition. The family slept inside the wagon until it became too crowded and thereafter the boys took to tents. “I wanted to be a memory maker,” McIntosh explains, “I wanted to make my kid’s childhoods different.”

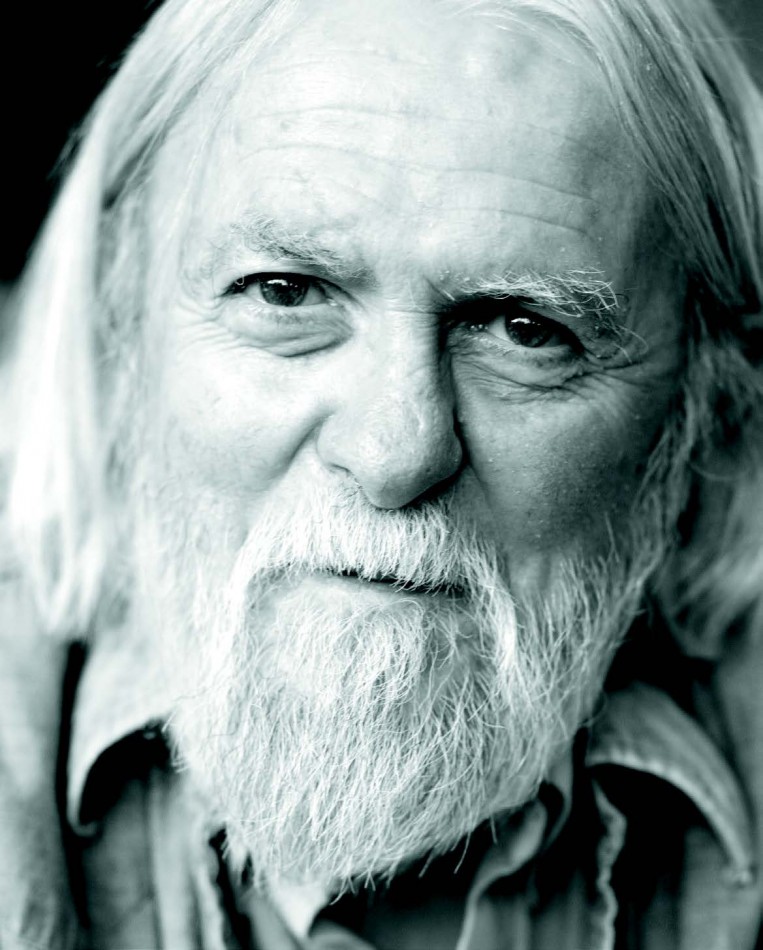

Principia Mathematica John Stelzer, 71 Logician & mathematician, Roseburg

Dr. John Stelzer was a catalyst for two major beginnings in world history. The Umpqua Community College professor came from Montana to Roseburg in a potato truck carrying logs that he would use to build what has been his home since the late ’60s. Stelzer chose Oregon because he knew it to be free and off the path; it was a place where he and his wife would be left alone and “if the house fell on our heads, it was our problem.” In the ’60s, he was a revolutionary in a very real way.

1859: You have a BA in mathematics from University of Maryland and a PhD in philosophy from Stanford University, how have these topics figured in your life?

JS: My main interest in philosophy is logic, which is also the foundation of mathematics. Primarily I’m interested in two logicians—the British Bertrand Russell and the Austrian-American Kurt Gödel. I’m fascinated by the foundations of mathematics, that is, what makes it work? Why do people believe in mathematics? You give over your ten dollars at a store and you get change, but what is it that makes the change right? Why do we put our faith in mathematics?

1859: Aside from your classes in world religion and philosophy at Umpqua Community College, how else have you employed these principles in your career?

JS: I worked for NASA on the first-man-in-space mission in 1963 as a research programmer. I was employed to solve the equations that would get man up into space successfully. Everyone needed to know exactly when we would be shooting him off—they wanted to watch and take pictures for the papers. I was the guy who had to tell them when. We figured this out with the calendar, the moon’s position, gravitational pull, et cetera. We put that guy up there and it worked.

Logic became useful for my work on the instructional uses for computers. I was in the Navy for four years beginning 1957. I was overseas at one point and I needed to learn about new radar systems. The only way to do that back then was to send me away from my station to somewhere where I could learn, which left a hole where I should have been. I began speculating about electronically sending information to people in the field and not physically bringing them to the information. I started work on a computer system that could be used to electronically transfer subject matter. This was the beginnings of the World Wide Web. In 1970, the United States Department of Defense sponsored me to research that technology, which I did for another two decades.

1859: What are your current projects?

JS: The classes I teach at the Umpqua Community College are based online and, as such, I am pioneering a new way for education. I have two CD ROMs—one for philosophy, one for world religion. Students really gravitate towards this method of learning because it gives them more flexibility and freedom. Also I can teach as many students as want to learn these subjects through this medium. I create mp3 files of my lectures. The students then take road trips, listening to the lectures in their car with a group of friends. They have a lot of fun with that.

Playing His Own Tune Murray Huggins, 41 Bagpipe maker, Medford

When a young Murray Huggins told his father that he planned to dedicate his life to making bagpipes, the reaction was lukewarm. “We’re not even Scottish!” says the Ashland native, who, at 9, asked his parents for bagpipe lessons and at 16 started reading up on the skills needed to make Scottish Highland bagpipes. Today pipers from around the world call on Huggins for his handcrafted Colin Kyo Bagpipes, which Huggins makes from start to finish working out of the workshop in his garage. His solo operation is not unlike the way that Huggins describes the bagpipe itself. “It’s a single instrument,” Huggins says fondly. “But to hear it you would think there are several instruments being played at one time.”

Sky’s the Limit

Kiera Brinkley, 16

Dancer, Portland

Leotard: $30. Stage makeup: $10. The reaction from students when Kiera Brinkley gracefully pirouetted and cartwheeled at her high school’s annual diversity assembly: “Complete shock,” says Brinkley, who lost both of her hands and legs to a bacterial infection when she was a toddler. “Then they gave me a standing ovation.” Brinkley is no stranger to the stage. She started dancing on her own as a little girl, learned tap and jazz in middle school, and recently performed for students at the Juilliard School of Dance in New York City. Still, she never gets over the wide-eyed looks of amazement she gets when she ditches her wheelchair and busts a move. “Dancing,” she says, “shows people that I’m capable of doing anything.”

Grace in Service LaVerne Bagley Brown, 80 Portland

Why: The lifelong social worker, community volunteer, and Urban League board member has donated thousands of hours to improving the lives of African-Americans living in Portland.

There was one thing LaVerne Bagley Brown could count on during her stint as an adoption social worker in 1950s Portland. “When I would finally meet the adoptive parents in person, their reaction was usually something like, ‘Wait, you’re black? You didn’t tell us that on the phone,’” says Brown, chuckling. “Some were very arrogant, but most were kind in the end.”

Brown’s biography is full of anecdotes that tell the tumult and pride of the African-American experience in Portland. The oldest of seven children, she was, in 1946, the first black student to attend West Linn High School. “At our sixty-second reunion, I saw the boys who used to call me names. … I didn’t tell them I remembered who they were.” She graduated from Marylhurst College in 1951 only to be repeatedly passed over for civil-service jobs because of her race; and she helped to register black voters before Rosa Parks even boarded that bus in Alabama.

These days Brown is a regular volunteer for the Portland Visitor’s Association and various senior services, and is also an active Urban League board member. Reflecting on a life of community service, LaVerne says, it was an “easy” choice. “You have to be thankful for what you have and share what you’ve been given.”

“We need equity and opportunity across a society,” he says, “but if you address needs of the poor, without taking care of the land, air, water and stable global climate, you won’t have long-term economic development.”

–Spencer Beebe, founder Ecotrust

Father Earth Spencer Beebe, 63 Environmentalist, Portland

Why: The founder and president of Ecotrust has shown a lifelong commitment to conservation and economic development

It’s a typical day inside the Pearl District headquarters of Ecotrust in that its founder and president, Spencer Beebe, has just returned from ten days trekking through some remote backcountry. Dressed in jeans and a white T-shirt, Beebe’s mad-professor hair seems especially unruly as he recounts his visit to the verdant Haisla First Nation region in Kitlope, just outside British Columbia.

“We mapped the largest temperate rain forest in the world there,” he says, as photos of azure waters swipe across the screen of his laptop. “It had been there 10,000 years, but no one had actually mapped it.” Ecotrust also helped the Haisla people ensure the permanent protection of their 800,000-acre river basin, which the organization touts as one of the biggest in the world. “There are only around 1,000 of these people left,” he says. “We simply don’t know if there will even be Haisla in the future.”

Ecotrust’s commitment to social, economic, and environmental well-being would seem obvious, but that is, Beebe says, exactly what is missing from many well-meaning conservation organizations. “We need equity and opportunity across a society,” he says, “but if you address needs of the poor, without taking care of the land, air, water and stable global climate, you won’t have long-term economic development.”

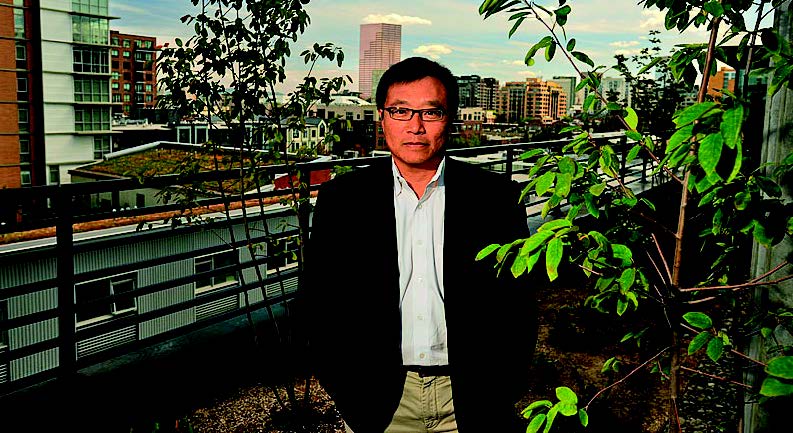

Adventurous capitalist Dave Chen, 49 Venture capitalist, Portland

Why: By investing big bucks in the sustainability sector, the founder and CEO of Equilibrium Capital Group is keeping emerging businesses in the green.

Ask Dave Chen to pick his favorite accomplishment in 2009 and it won’t be his chats with White House sustainability advisors about how our country can leverage the financial markets and entrepreneurs with long-term conservation goals. Nor will it be his collaboration last winter with Governor Kulongoski and Oregon’s most influential green experts on creating a distinct plan for how the state will best benefit from its share of the $787 billion recovery act.

“Those were important, yes, but the most exciting thing we’ve done lately is invest in EQRM,” says Chen of a five-month-old Portland start-up he says is “filling a massive financing hole” in the energy efficiency sector. “We are foremost investors and company builders. We do work to inform public policy, but our focus isn’t to get sucked into the vortex of politics, rather invest in the future.”

“There is a spirit of innovation that makes us a powerful indicator of things to come. Personally, it inspires me to keep pushing us forward.”

–Dave Chen, Equilibrium Capital Group

Looking out onto the Pearl District from an eighth-floor conference room at Equilibrium Capital Group’s downtown offices, Chen reflects on Oregon’s unique position for leading the emerging sustainability business sector. Compared to the rest of the nation, he says, our state has an unusual economic footprint in that, for being relatively small, we can do everything. “Manufacturing, technology, renewable energy, wind assets, solar assets and intellectual property,” says Chen. “There is a spirit of innovation that makes us a powerful indicator of things to come. Personally, it inspires me to keep pushing us forward.”

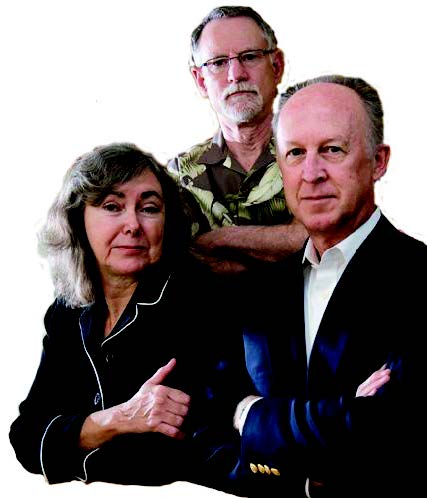

Big Tobacco’s Legal Nightmare Bill Gaylord, 62, Linda Eyerman, 61, Todd Bradley, 58 Lawyers, Portland

Why: They are the veteran attorneys who took on cigarette-maker Phillip Morris and, in 1999, won $80 million: one of the largest awards ever for a smoking-related death. In 2009, after ten years of appeals and three trips to the U.S. Supreme Court, the verdict was finally upheld.

Bill Gaylord: We opened Jessie Williams’ case in fall of 1996, and he died of lung cancer in 1997 at age 65. We liked him and his family and believed strongly in his case.

Linda Eyerman: We knew it was going to be a crusade: David vs. Goliath.

Bill Gaylord: Tobacco litigation is primarily about fraud. This case was about taking on an entire industry; one that conspired very directly starting in 1953 to do whatever it had to do to sell a product they knew was deadly. They’d known for years they were committing homicide, around 40,000 deaths a year, and put millions of dollars they had toward defending themselves. Very few plaintiffs had a chance.

Linda Eyerman: The timing was also right. In the late 1990s, the Minnesota attorney general forced tobacco companies to disclose numerous confidential documents.

Todd Bradley: Having these publicly available documents allowed us to put the case together more easily and work with other local firms too. Those were very long and unique collaborations. We are all still friends, actually.

Bill Gaylord: I’d say our being in Oregon was a huge factor. There is a mentality here about wellness, personal responsibility and the value of citizen juries. Our system honors those legal processes and supports an individual’s right to stand up against impossibly powerful corporations.

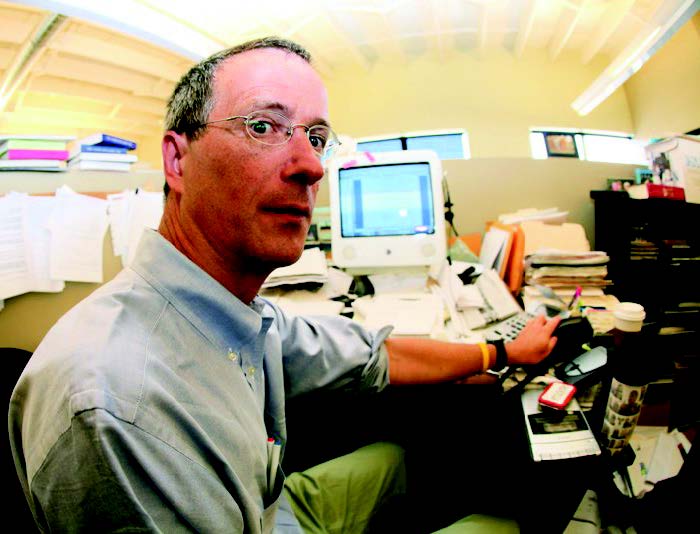

Where No Dogs Lie Nigel Jaquiss, 47 Journalist, Portland

Why: The Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter for Willamette Week broke the sex scandals involving former governor Neil Goldschmidt and 2008 mayor-elect Sam Adams

1859: You were immediately labeled a muckraker when your story was published last winter about Mayor Elect Sam Adams having lied about an improper relationship with an underage male. How did it feel to be so vilified?

“Mostly I felt great relief that I was done with the story and was finally able to put in print what I knew to be true. People reacted very strongly, which I understand. Sam was the first openly gay mayor of a big city and a leader of a movement that’s very strong here.”

1859: But you did feel vindicated?

“Yes. It was clear that the mayor had told a number of lies and continued to lie after the story. That hurt him a lot. The story is true, and this has helped quiet some, not all, of the hate mail.”

1859: This was a different kind of a fallout when compared to that of the Neil Goldschmidt story in 2004, which untangled the ugly 30-year-old cover-up of the former governor’s three-year sexual affair with a teenage girl in the 1970s.

“There was a lot of disgust with that one too, but Goldschmidt was in his 60s when it broke. Sam was, and is, at the start of his political career. But I’d say both scenarios have made Oregonians look at their city and state and ask: ‘What do these scandals say about us?’”

1859: After such a swell of hub-bub, it seems as if the Sam Adams controversy has nearly blown over. Have we moved on?

“Well, I think the recall process is not going well well. They need about 50,000 signatures and are far short of their goal. It’s still an open question as to whether he will be an effective mayor. I don’t think he has regained enough of the trust and confidence he lost that he needs to do it.”

1859: Political sex scandals are utterly commonplace in larger cities and states. Do you think your reporting took some of the sheen off of our utopia?

“I do think there is naiveté here about corruption, but I think that’s also why a lot people come to Oregon. There is still a belief here that government can be a force of good; a strong ethic of civic engagement. We are less jaded, so when leaders like Sam show they are all too human, people don’t know how to react. Corruption is endemic to human existence. It doesn’t know geographic boundaries.”

Crusader for Comfort Stormy Ray, 54 Activist, Salem

Why: A mother, grandmother and longtime sufferer of multiple sclerosis, Ray has worked tirelessly for more than a decade to ensure qualified patients’ access to medical marijuana.

When her husband was thrown in jail for planting marijuana to help her ease the pain of M.S., Stormy Ray became the accidental public face of chronic pain. “I had never done drugs in my life, but marijuana took me from being a prisoner in my own body to being able to communicate again,” she says of the palliative effects marijuana has on her condition. “My eyes were wide open.” Working closely with legislators and attorneys, Ray fought for getting Oregon’s Medical Marijuana Act on the ballot in 1998. (More than 600,000 Oregonians voted it into law that November.) Today, via her nonprofit, the Stormy Ray Foundation, she advocates tirelessly for better access to marijuana for those patients who are qualified under the law to use it. “There is more need than ever,” says Ray, who recently testified with other patients at hearings in Salem about possibly adding more qualifying medical conditions, such as Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, to the law. “The fight is far from over.”

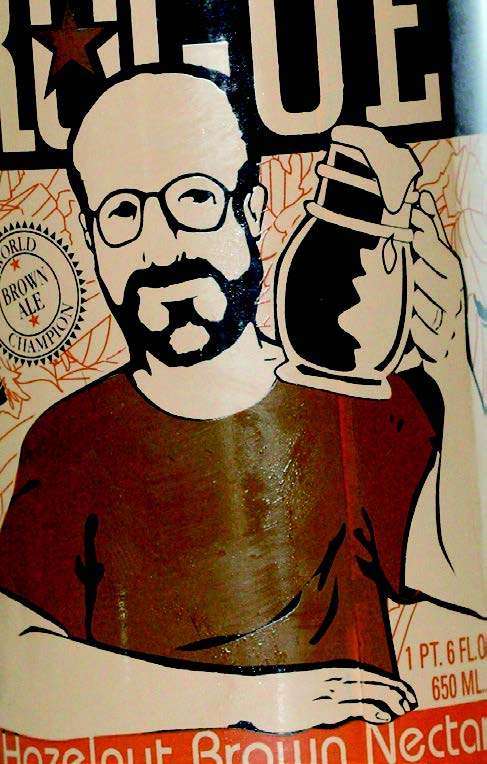

A Rogue of a Brewer John Maier, 54 Brewmeister, Newport

Rogue Brewery brewmeister, John Maier, left aerospace engineering for beer. Once a technician working on radar for the F-14 Tomcat at the Hughes Aircraft Company, Maier found a separate peace in working with hops. In 1989, he started working on the first batch of Rogue Ales at the christening of its Newport brewery. Twenty years and counting, Maier has been the technician and craftsman behind some of the Pacific Northwest’s best brews. We asked Maier for his top five favorite beers outside of the Rogue family of brews.

Anchor Steam, an amber from San Francisco’s Anchor Brewing

Sierra Nevada Celebration Ale, the Chico, California dry-hopped ale

Aecht Schlenkerla Rauchbier (Marzen), a Rauchbier-style beer from Bamberg, Germany

Hansen’s Oude kriek, a Belgian lambic-style beer

Orval, a beer made by Belgian Trappist monks

Tackling the Toughest Race Rachael Scdoris, 24 Sled Dog Racer, Bend

Scdoris, a pretty, quick-witted woman who also happens to be legally blind, pushed past physical, cultural and political boundaries to enter her first Iditarod in 2005, competing against the hard-edged mushers who dominate the 1,100-mile slog across the Alaskan wilderness. Scdoris now has two Iditarod finishes to her credit, and respectable ones at that. Having grown up around her father’s sled dogs, Scdoris started driving her own team of dogs at age 11, competed in her first race at age 12, and at age 15 was the youngest person to finish the 500-mile International Pedigree Stage Stop Race in Wyoming. After graduating from high school, Scdoris set her sights on the Iditarod. Getting to the starting line of the iconic race is a time-consuming and expensive process for any athlete. Scdoris had the additional hurdle of convincing the Iditarod Trail Committee that her visual guide wouldn’t give her an unfair advantage over sighted competitors. Once rules were established, Scdoris proved her mettle.

This fall, the intrepid Scdoris found a new frontier in setting out on a 6,000-mile tandem bike ride from Anchorage, Alaska to Cancun, Mexico to raise awareness about global warming. This colossal journey could also set the stage for a shot at the 2012 Paralympic tandem biking race in London.

Origin of a (sticky) Species Kellar Autumn, 44 Gecko Adhesion, Portland

Turns out geckos aren’t just good for insurance mascots. Thanks to the millions of microscopic hairs on its toes, one tiny gecko sticks with enough force to suspend an NFL linebacker. “Gecko adhesion isn’t just super sticky,” says the Lewis & Clark University biology professor and inventor of gecko-inspired adhesives. “It’s controllable, durable, hypoallergenic and self-cleaning.” A gecko-spider battle on the ceiling of his vacation hotel in Hawaii launched years of research and discovery. Here are some of the amazing applications that could come out Autumn’s research.

Robotics: Most robots can’t climb worth a damn. Give them legs with gecko-like adhesives for search and rescue missions and space exploration.

Electronics: Replace tiny joints in circuit boards and semiconductors with gecko adhesion for cheaper more durable gadgets.

Construction: Imagine building a house without toxic glues, or screws and nails for that matter.

First aid: Autumn’s lab has the prototype on a true no-ouch bandage.

Fashion: Strapless shoes, strapless dresses, oh my.

Sport: Gecko technology could change the sport of rock climbing, making impassible routes possible and giving big-wall climbers lightweight protection.

Microscopic surgery: Gecko adhesives can be used to pick up tiny objects and gently set them down.

1859: Why geckos?

A: I became interested in gecko adhesion ten years ago during a vacation in Hawaii. I was in a little hotel near Kealakekua Bay and, while I was in bed, a huge spider crawled out across the ceiling. I’m a bit arachnophobic, so I was trying to work up the courage to deal with the spider when a tiny gecko came out on the ceiling too. The gecko and the spider had an upside-down battle right there above me. The gecko won easily and knocked the spider off (fortunately not on me!). This made me wonder how the gecko could run so easily on the ceiling, and why it was so much better at sticking than the spider.

1859: What sorts of breakthroughs you and your lab have had so far?

A: My moment of curiosity in Hawaii inspired our study of the force generated by a single gecko foot-hair (published in Nature in 2000), which was a first step in solving the mystery of how geckos stick.

Initially, this project did not go as planned. Once we had isolated one of the microscopic hairs, or setae, on a gecko’s toe, we couldn’t make it stick. The frustration continued for months, leading us to hypothesize that a chemical component secreted by the gecko might be required for seta adhesion, as is the case for many insects. Instead, once we realized that a gecko first places its feet on the surface and then pulls inward toward its body, we discovered that attachment and detachment in gecko setae are controlled mechanically, not chemically.

Adhesion in gecko setae requires a small push perpendicular to the surface, followed by a small parallel drag. When properly oriented, preloaded, and dragged, a single seta can generate over three orders of magnitude more force than required to hold the animal’s body weight. All 6.5 million setae on the toes of one gecko attached simultaneously could lift 133 kilograms (293 lbs).

The next step was figuring out the molecular mechanisms of adhesion. We discovered that weak molecular attractions called van der Waals forces are sufficient to make geckos stick. Because van der Waals interactions depend more on geometry than chemistry, we proposed that the size and shape of the structures—not their chemical composition—determine the stickiness. To test this hypothesis, we used two polymer materials to synthesize the world’s first gecko-inspired adhesive nanostructure.

Our research showed that we can enhance adhesion, just as geckos have, simply by dividing a surface into small protrusions to increase surface density. We now have a number of patents on gecko-like synthetic adhesives (GSAs). Our work on gecko adhesion has grown into a new field of research at the interface of biology, physics and materials science.

Over the past eight years, we have also discovered that gecko setae are self cleaning, don’t stick to themselves and are rate-dependent. We are working hard to understand the fundamental principles underlying these properties.

It’s remarkable that each time we figure out something about the gecko system, multiple new questions emerge. One new opportunity is the use of gecko-inspired synthetic adhesives as physical models to test our understanding of the system. We can learn a great deal by observing how these synthetic analogs can—and cannot—measure up to the material on real gecko toes.

The physics of surfaces in contact is a hot area of research. Our new theories and methods are revealing how dynamics at the nano-scale level may affect macroscopic contact forces and fracture energies. There is a real interdisciplinary synergy here: progress in surface science has been fundamental in the study of gecko adhesion, which in turn is advancing understanding of the physical mechanisms that cause adhesion and friction. Our most recent study suggests that geckos, atoms, and earthquakes may share common friction mechanisms!

1859: How might your research be applied to the real world?

A: Gecko adhesion has become a paradigmatic example of bio-inspired engineering (see “The Gecko’s Foot” by Peter Forbes, Fourth Estate, 2005). Micro-electrical interconnects, wafer alignment, micromanipulation and robotics are just a few of the many possible applications for GSAs. Because gecko adhesives do not rely on soft polymers or chemical bonds, they may someday replace screws, glues, and interlocking tabs in assembly applications such as automobile dashboards or mobile phones.

Adhesive nanostructures relying on van der Waals forces and made from hard, elastic materials should be able to re-bond dynamically following fracture, allowing for self-repair. With a clever joint design that takes advantage of the directionality of gecko adhesives, self-disassembly for repair and recycling should also be possible.

Because they can be self-cleaning, adhesive nanostructures have the potential to reduce our reliance on cleaning solvents and surface preparation, reducing cost and environmental impact. Using nontoxic and nonirritating materials to fabricate synthetic setae may enable biomedical applications such as endoscopy and tissue adhesives.

I think it is a useful lesson that the study of a lizard can have such broad and numerous applications ranging from nanosurgery to aerospace. Genrikh Saulovich Altshuller, the inventor of the so-called “Teoriya Resheniya Izobreatatelskikh Zadatch” (Theory of Solving Inventive Problems—or TRIZ) said: “In nature, there are many hidden patents.”

I think what he was getting at was that biological systems arrive at solutions that are unpredictable and, in some cases, unimaginable until we see them. This underscores the value of basic, curiosity-based research. Geckos have solved the problem of sticking to things in a completely different way than engineers do—or at least used to. Would we have considered making an adhesive from a nanostructure if geckos had not evolved?

I like to think of biodiversity as a huge design library. There are millions of species out there waiting for us to discover their unique solutions to life’s myriad problems. But the scary thing is that extinction is taking these books off the shelves faster than we can open and read them. Even if humanity’s primary aim is economic progress, we must slow the increasingly rapid rate of species extinction before many more valuable secrets of nature are lost forever.