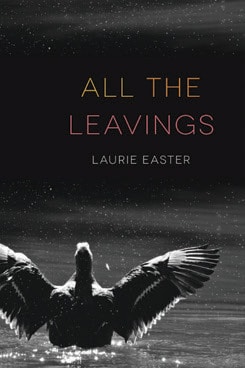

A writer living off the grid navigates the wilds of nature and the human heart

interview by Cathy Carroll

Laurie Easter lives off the grid on twenty-eight forested acres in a funky little cabin on the edge of wilderness in southern Oregon. Her essays have been awarded fellowships by the prestigious Vermont Studio Center and Playa in Summer Lake, published in many literary journals and anthologies, nominated for a Pushcart Prize and listed as notable in The Best American Essays 2015. She holds degrees from Southern Oregon University and Vermont College of Fine Arts.

All the Leavings, being released in October by OSU Press, is her first book. The memoir navigates the rugged terrain of an alternative lifestyle and the hazards of the human heart, from encounters with cougars and the dynamics of mother-child relationships, to the destructive power of wildfires, the home birth of her second child and community bonds challenged by a tragic suicide. She takes readers deep into the heart of a still-wild Oregon, perilous yet rich with natural beauty. Tales of at-once relatable people unfold while capturing an interior life and the cinematic beauty of the West in prose that is, ultimately, a redemption song.

Can you discuss your choice of a nonlinear, loosely chronological approach to this memoir?

I find that even though life unfolds in a chronological fashion, the way our minds process memories—especially traumatic events—is not linear, but emotional and fragmentary. Sometimes a chronological narrative approach makes sense, and I tell a story that moves from A to B to C. Often, though, my writing reflects a nonlinear and experimental quality. I thrive on playing with fragments, their juxtaposition and metaphoric implications. The challenge is in the arrangement of each piece to create work that is formally creative yet still highly readable and engaging. Two of the essays in the book are in the forms of crossword and word-search puzzles.

Tell us about life off the grid in southern Oregon and how it has helped and or hindered your writing.

My husband and I moved to southern Oregon in 1989 when we were expecting our first child. We wanted to raise our family rurally, in a place with strong community and an alternative lifestyle, and we knew a few people who lived here. I lost Steve to cancer in 2018, so life off-grid is much more challenging now, as I am solely responsible for the water and power systems, mowing and weed whacking, firewood, repairs, etc. This lifestyle has helped my writing by giving me lots of material to work with, although the events in All the Leavings take place before Steve’s death. Learning how to survive independently will be my next book.

In writing about deeply personal things, how did you negotiate that territory knowing that others might recognize themselves in the book?

One cannot write memoir without writing about other people because our experiences are relational to others. I commit myself as a narrator to a compassionate viewpoint. This does not mean I hold back from exploring challenging topics. But I try to be harder on myself than others. To protect privacy, I have changed a few names and identifying details.