written by Chris Lozier | featured image by Talia Galvin

“It’s a lot of hands-on labor,” said co-proprietor Georgia Nowlin. “It’s like owning a restaurant—you’re the cook and chief bottle washer.”

Georgia and David Nowlin, along with David’s father, R.L., founded Brandy Peak in 1993. Over the past two decades, Brandy Peak’s spirits have garnered national attention. Its aged pear brandy won the only double gold medal awarded at the American Distilling Institute’s 2009 Brandy Conference, joining Brandy Peak’s other gold medals from some of the world’s most prestigious competitions.

“The quality of the fruit determines the quality of our brandy,” said Georgia. “If we get good fruit, that is where the art comes in. You can transfer that into your beverage.” Pears are cold-shipped from the pear-growing neighboring region of the Rogue Valley to Brookings, where the Nowlins let them ripen under the sun. They crush and mix the pears with yeast and water, making a mash that will ferment for several days, allowing the yeast to convert the sugar to alcohol. Finally, Nowlins heats the mash in the still to produce the distillate, a pear eau de vie, which, after aging five years in oak barrels, becomes aged pear brandy.

When Brandy Peak started up its wood-fired still two decades ago, it was one of two craft distillers in Oregon. Driven by top-notch agriculture, the buy-local movement and a state regulatory architecture that allows small distilleries to compete equally with international conglomerates, Oregon is now home to more distilleries per capita than any other state. There are sixty distilleries including bourbon makers in Portland, Corvallis and Joseph; vodka crafters in Warren, Spray and Dundee; gin producers in Sheridan, Ashland and Newport; and absinthe diviners in Medford.

Oregon’s documented distilling history began in 1934 when Hood River Distillers became Oregon’s first licensed distiller, making apple and pear brandies. Following the success of Oregon craft brewers, distillers today focus on quality small batches that encompass such spirits as bourbon, gin, rum, aquavit, vodka and liqueurs. “We’ve done it with wine and beer, why not spirits?” noted Ted Pappas of Big Bottom Whiskey in Hillsboro. “We have the right climate, raw materials and a great talent pool. It’s a natural fit for our state.”

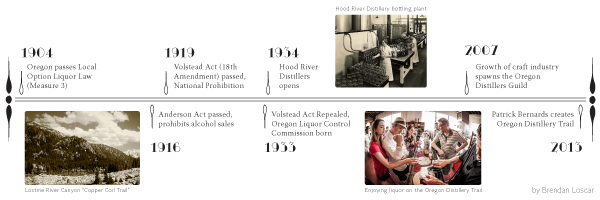

This wasn’t always the case. In 1904, and amid a rising tide of teetotalers, municipalities in Oregon received a local option to vote themselves wet or dry. The Anderson Act of 1916 prohibited alcohol sales in the state. The party didn’t stop. Moonshining became widespread, with many illegal stills operating in Central and Eastern Oregon. Lostine River Canyon in northeast Oregon earned the nickname “Copper Coil Trail” for the many stills operating there.

Three years later in 1919, the Volstead Act, known as the Eighteenth Amendment, spurred national Prohibition. While the penalties for Oregon’s moonshiners increased, the ‘shiners stayed on their game and one step ahead of the law, bootlegging loads of illegal liquor to surrounding states.

The Volstead Act was repealed on December 5, 1933. Four days later the Oregon Liquor Control Commission was born.

Fermentation

The growth of the craft industry in Oregon spawned in 2007 the Oregon Distillers Guild, the first of its kind in the nation. Its mission is to bring about beneficial legislation for craft distillers, and to develop industry programs, education and marketing. Other states soon reached critical mass and followed Oregon’s lead with guilds of their own.

One of the guild’s most public efforts materialized last year, when Patrick Bernards of Bull Run Distillery created the Oregon Distillery Trail, a mapped consortium of about thirty participating distilleries around Oregon. This increasingly dotted map puts in perspective for trail-goers the breadth of the Oregon craft distilling industry.

The universe of the Oregon craft industry, though, is bigger than the guild and its members. The densely populated Distillery Row in Portland is another spirited outgrowth of the industry.

Founders of six distilleries worked together to create a map, a passport and a tour of their distilleries and tasting rooms in the warehouse district of Southeast Portland. “Distillery Row is a huge part of our business, and most of our walk-in traffic is related to it,” said Sebastian Degens of Stone Barn Brandyworks, which offers twenty seasonal spirits and whiskies.

Distillery Row has also created a micro-economy of its own with a cadre of rickshaw and limousine tour companies for hire. PDX Pedicab’s rickshaw tours give Distillery Row-goers a personalized experience without having to drink and drive. Pedicab’s Kyle Kautz said the company has hired new employees just for the Row tour and estimates that they do more than 300 Row tours per month in the summer.

For every bottle of liquor sold in Oregon, 37 percent of the price goes back to local budgets to fund police, education and health care. The agency projects it will return $441 million to local and governments this biennium.

Whether to see a distiller from Distillery Row or another farther afield, visitors come to learn about distilling operations, to sample innovative spirits and to meet the producers—a liquid form of the local food movement pervasive throughout the Pacific Northwest. “Making the connection with the actual company, with the story, with a Northwestern body, that made a big difference,” said Jerod Osborn, a visitor to Rogue Ales & Spirits in Newport. “What really set that distillery apart for me was the stories.”

The most compelling aspect of the local industry, though, comes from the abundance and quality of local agriculture. Oregon is a national leader in wheat, cherry, pear and berry production, giving distillers privileged access to a wide variety of fresh ingredients. For instance, distillers in Portland are wedged between 5,000 acres of berries in Washington County and 11,000 acres of pears in Hood River County. Last year, Clear Creek Distillery used 1.25 million pounds of Oregon fruit, buying pears from Duckwall Fruit.

Farm to Flask

Duckwall’s Ed Weathers said that, while most of their clientele wants young pears that have yet to ripen, Clear Creek buys ripe pears of unusual shape, which helps growers to use more of their harvest.

More than 400 Oregon-made spirits account for more than a fifth of OLCC’s entire selection. John Ufford of Indio Spirits in Portland said variety is a big factor in the industry’s success. Indio’s Oregon marionberry vodka, made exclusively with Oregon marionberries, is one example. “When I started, creating unique flavors was kind of the point,” he said.

“We live in a cornucopia,” Degens of Stone Barn Brandyworks acknowledges. Stone Barn buys fruit for its quince liqueur from Oregon Quinces’ orchard twenty minutes away. Likewise, Aria Gin buys its Angelica Root from Grants Pass, Stein Distillery uses Hermiston corn, and Bull Run uses Southern Oregon barley.

Brad Irwin of Oregon Spirit Distillers in Bend points to the “immediate access to great grains and fruits” in Oregon. Irwin buys grain—more than one hundred tons this year—from Bishop Farms in Bend which, in turn, buys Oregon Spirit’s products as company gifts.

Some distillers even complete the supply-chain cycle themselves. “We have single malt vodka and single malt whiskey whose ingredients we grow ourselves,” said Rogue Ales & Spirits president Brett Joyce. Rogue spirits are distilled at the Newport headquarters on the coast, but Rogue grows and malts barley on its farm in Tygh Valley. The company also grows peppers for its Chipotle Spirit at their hopyard in Independence, then smokes the peppers at the distillery.

Farther east in the tiny town of Joseph, Stein Distillery and tasting room sits on North Main Street. Behind it sits acres of grain. The Stein family plants, grows, harvests, and mills their own rhubarb, rye, wheat and barley within a few miles of the distillery. In the case of Stein’s rye vodka, rye whiskey and rhubarb cordial, the same hands completely process all the ingredients from planting to bottling.

Whiskey Regulation

“Spirits made from raw grain hold a bolder, more flavorful profile,” Heather Stein offered. Austin Stein said the family started the distillery in 2006 because growing their own grain on their three-generation family farm allowed them to “manage the distilling production from the ground up,” a philosophy that has earned them shelf space in six states.

Likewise, Mike Sherwood of Sub Rosa Spirits in Dundee uses homegrown saffron to make his tarragon and saffron vodkas, which have brought variety to a straightforward liquor and attained a cult following among mixologists.

In the plains of Central Oregon’s high desert, it would be a difficult burden to grow water-intensive fruit or grain. Nonetheless, the hot and dry climate is hospitable to juniper and juniper berry, which is the predominate flavor in gin. Here, Bendistillery grows all of the ingredients for its Estate Gin onsite. The most awarded craft distillery in America, Bendistillery distributes to more than thirty states. CEO Alan Dietrich says the nationwide penetration of Oregon spirits definitely bolsters the state’s reputation as the center of craft beverages in the country.

If Oregon’s agriculture is the most obvious ingredient for local distillers, the state’s regulatory system is another staple. Oregon is one of eighteen states in which liquor distribution is controlled by the state. It may, at first, seem a bit antiquated, but the system acts as a regulator and distillery incubator. In Oregon, all distilled spirits sold in the state must first pass through Oregon Liquor Control Commission’s 230,000 square feet of warehouse space. Once there, it is catalogued and picked for shipment to more than 11,000 restaurants, bars, and grocery stores and an additional 250 liquor retail outlets throughout the state.

Gross revenue from liquor sales in the current 2013-2015 biennium is expected to reach $1 billion, the greatest in the OLCC’s eighty years. For every bottle of liquor sold in Oregon, 37 percent of the price goes back to local budgets to help fund police, education and health care. The agency projects that it will return $441 million to local and state government this biennium.

In many other states, where liquor is not controlled at the state level, local distillers struggle with distribution and sales. The big guy wins. Big box grocery chains tend to buy in bulk and carry only the best-selling national brands to maximize sales while leaving little shelf space for local craft liquors.

In Oregon, however, the OLCC buys liquor at a set price and sells it to retailers without incentives for buying in bulk. Retailers can test the market with small batches—even single bottles—of new local creations without the risk of holding bulk inventory.

“We’ve got a good working relationship with the OLCC,” said guild president Pappas. One example of that relationship resulted in a law which allows distillers to sell spirits at special events, and puts distillers at parity with craft brewers and winemakers. “When someone makes a connection with our product, they can actually buy it there and take it home,” said Ryan Csanky of Aria Portland Dry Gin.

The OLCC also supported legislation that allowed distillers to establish their own tasting rooms. Michelle Ly of Vinn Distillery said Vinn’s tasting room on Distillery Row is essential to gaining new customers. Vinn is the only distiller of baijiu in the U.S., a rice-based spirit similar to white whiskey. Ly said few people are familiar with Vinn’s rare spirits, and the tasting room in Portland’s Distillery Row allows them to “get the spirits to their palate so they can get a sense of what it is.”

Some consumers, business groups and the Northwest Grocers Association (a trade organization representing grocery chains such as Fred Meyer and Safeway), prefer that the government hand over the keys to private industry. Following a legislative victory that privatized liquor sales in Washington in 2012, the Northwest Grocers Association is pushing for a similar triumph in Oregon.

With Washington as the test piece, Oregonians watched with interest. Among other things, the initiative allowed grocery stores larger than 10,000 square feet to privately sell liquor, which supporters claimed would increase selection and decrease price.

Instead, prices soared, selection fell and profit collapsed. Dietrich of Bendistillery watched retail sales fall 50 percent in Washington in the ensuing year. John Ufford said Indio Spirits had to dramatically cut its margins to compete, but that retail prices are still $9 per bottle more than in Oregon. “You can’t take the state of Oregon out of the business of selling booze without the state losing money,” said Steven Stone of Sound Spirits Distillery in Seattle. “You would need to raise taxes to retain the same level of revenue for the state.”

Stone noted that more than half of Washington’s small liquor stores went out of business because of increased taxes and fees. The problem, he said, was not privatization per se, but the language in the bill and the way it was implemented.

Duane Harris, owner of Liberty Lake Liquor & Wine in Liberty Lake, Washington, near the Idaho border, estimates he lost three-quarters of his business to Idaho because of the price increase. Harris said his best sellers are craft spirits and specialty spirits because, “large grocery stores don’t want to sell those products.” The same legislative ideas are now surfacing in Oregon. Recently, a group called Oregonians for Competition filed eight petitions aimed at privatizing and amending Oregon’s current liquor system. The eight are expected to be narrowed down to one, which will be on the November ballot.

Dawson Officer of 4 Spirits Distillery, a Corvallis upstart with a small distribution network, said he fears a future where only large stores carry spirits. “If the grocery stores won’t pick you up, you can’t sell your product,” he said.

Many expect this scenario in Oregon to play out much like it did in Washington. “People need to read what they’re voting for,” warned Pappas. “Do not make the mistake of Washington. It’s not about privatization versus state control, it’s about the bill. Read the bill.”

Tad Seestedt of Ransom Spirits in Sheridan said that the current political maneuvering is “threatening the welfare of smaller distilleries, especially those that sell only within Oregon.” If the current system remains intact, Seestedt sees a future that’s wide open for craft distillers. “There are so many possibilities for different products and styles.”

I own and operate a local Oregon distillery in Eugene. The Cottage Grove outlet is very pro-Oregon. If you ask they will bring in whatever you want. Most of our products are able to be ordered in single bottle quantities.

Photomatte: just checked and the Cottage Grove store has Desert Juniper Gin in stock and it also an Oregon product. It has been around since 1997 and holds a number of tasting awards. I'm biased but think it is the best gin ever.

Immediately upon reading this article I went to my local liquor store here in Cottage Grove (open 7 days a week!) only to find one of the bottles from the photo (the photo in the article showing 8 bottles of Oregon spirits). The one I found was the Snake River Stampede, from Indio Spirits in Portland. Reading the label's small print when I got home, however, led me to discover that Snake River Stampede is actually produced in Nampa, Idaho (about 30 miles from Boise)! I look forward to trying more of the featured bottles if and when my local liquor store starts stocking them.