written by Tricia Louvar | illustrations by Karen Eland

Bobby Grover held a coffee roaster’s concerto. He flipped through roaster profile sheets with printed tables and handwritten numbers inside the columns. “See, this one was 413 at 11:02,” said Grover, owner of Thump Coffee Roasters in downtown Bend. He rattled off numbers. His finger ran across the top of one grid. “This line here is like the coffee’s speedometer,” he said. The numbers corresponded to Fahrenheit and length of roasting time.

Burlap sacks filled with 150 pounds of Ethiopia, Colombia and Sumatra green beans waited in the roasting queue. Grover, who studied physics and finance, chose a life hunkered down in his roasting lab to test hypotheses and experiment with coffee beans. “Coffee is a ghost I’m constantly chasing,” he said. “It’s ever-changing … and elusive.”

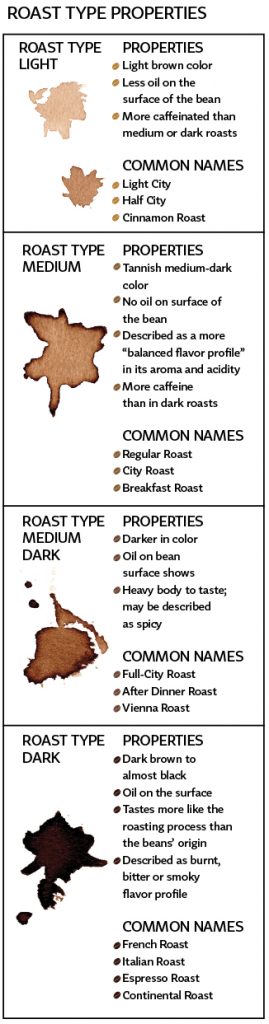

Oregon coffee drinkers get riotous about their roasted beans. Drinkers make alliances. Roasters systematize their best practices. Minutes can make or break a roastmaster’s micro-lot batch. We explore the art of roasting and why Oregonians are so coffee literate.

The Green-to-Brown Bean

Before delving the love affair with coffee, it must be known that unlike wine and beer, Oregon’s other beloved beverages, our terroir cannot grow coffee. Instead, the roasters rely on relationships with international farmers, brokers and importers. The world’s most plentiful coffee-producing countries—Brazil, Colombia, Vietnam and Indonesia—may be the origin of coffee beans, but many people touch a single bean before it ever gets roasted, ground, brewed and possibly milked or sugared.

Workers hand-pick the red coffee cherries planted on mountainous terrain. The average picker plucks 100 to 200 coffee cherries a day. The coffee fruit is then dry- or wet-milled, sun- or machine-dried, shelled and left with a green bean. Of those original berries picked, the process nets about 30 pounds of coffee beans. Decaffeinated beans undergo the caffeine removal process by way of chemicals or the Swiss Water Process (a chemical-free method).

The Oregon roaster works with an importer and the beans, in jute sisal bags, travel by ocean freight to the Tacoma, Portland or Long Beach, California ports. From there, the supply chain may require beans travel by rail or truck to a warehouse or to local roasters.

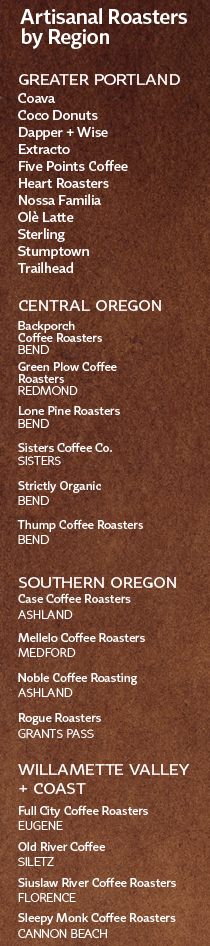

Once at the roaster, the roastmaster applies evenly distributed heat to the coffee bean, which brings out its natural flavor. All things affect the bean’s taste—soil health, elevation, harvest methods and climate. (For a quick guide to various roasts, reference the table on page 80.) Then a licensed Q grader, who has been certified by the Coffee Quality Institute, cups the roasted beans. Cupping, a formalized rating system, involves slurping and documenting.

Coffee beans come from varietals, much like wine grapes. Many coffee roasters provide details about their beans. For example, Coava offers a full history of the producer, location, elevation, taste notes, brew recommendations, varietal, processing and an informative paragraph about the producer printed on its 8-ounce bag of beans.

Most of the coffee we drink, however, comes from the sweeter Arabica species. Some roasters also blend Robusta and Arabica. The former is known for its bitter flavor and better value (on the commodity markets). Large corporations dominate the Robusta bean market, selling coffee cheaper because of the mass volume.

The Waves of Coffee

Culture waves shaped the coffee industry. Depending on your alliances and who in the coffee audience you’re talking to, some may agree we’re either living in or entering the Fourth Wave of coffee. Each wave marks specific booms in the coffee landscape—consumption, the rise of specialty coffees, companies investing in their people through education and certifications and now the delivery of artisanal coffees as subscriptions (like a wine club but for roasted beans).

Coffee has become an artistic craft as viable and studious as viticulture. Oregon has thrived beyond the comfy café prestige and professionalized the industry by creating the Oregon Coffee Board. Founded in 2014, the OCB acknowledges that coffee companies compete for business but say they are better if they work together and work as a unit for the betterment of Oregon coffee. OCB brings together sixteen Oregon coffee companies for best practices. It’s the first of its kind in the country. Nine elected members from the state’s coffee industry comprise the board and drafted its thirty-four-page bylaws.

Besides OCB, the Alliance for Coffee Excellence, headquartered in Portland, specializes in best practices and upholds the highest standards in the global coffee industry. It awards the coveted Cup of Excellence, the premier international coffee competition, with its most intensive, critical and juried award by international judges. The award celebrates the farmers and offers the winning beans in a live auction.

The Roasting Boom

Consider the green coffee bean a roast master’s blank slate. Coffee roasters must decide how best to bring out the beans’ inherent flavors, and make you want to come back for more. A cup of ‘joe means more than comfort in a recyclable paper cup. A coffee roaster wants your business, needs a constant thrum of foot traffic and notices how long you’re staying between cups. How many cups of coffee do you have to sell to pay for the 8-ounce coffee bags, the stickers on the bags, the metal twist tie at the top, the operations, the development, the resources and the barista’s loyalty to stay put and offer exceptional customer service?

“To make a living in Portland, coffee shops really have to diversify their brand,” said Lora Woodruff, owner of Third Wave Coffee Tours. “You don’t find just a coffee shop. They either go the wholesale route or retail route as well at multiple locations.” She carved out a niche for herself in the food and beverage tourism industry, with patrons from as far Australia and British Columbia traveling to Portland just to take her coffee tour. “There are not many of us [coffee tour guides] in the U.S. yet. I only know of other ones in Seattle and Vancouver (BC) at this point. We’re really a subset of the food and beverage tourism sector, like wine, beer, chocolate, food carts.”

Entering the specialty coffee scene is not cheap. Roasting machines reach prices on par with luxury cars. Smaller roasters, such as Ole Latte and Coco Donuts, partake in the co-op style and roast at Aspect Coffee Collective rather than investing in their own roaster. “Aspect has given us a great opportunity to get into the roasting game, buy higher quality green beans to roast and offer to our customers rather than simply purchasing roasted coffee from another roaster,” said Ian Christopher, co-owner and roaster at Coco Donuts.

RRRoasters at Aspect Collective rent time on a Probat L12 roaster. For those interested in learning the art of roasting or opening their own café, Aspect offers a “ghost roasting” program, customized to fit needs. “The upfront cost of acquiring a roaster and a commercial space, for a company that plans to grow, it’s a stop-gap solution and, eventually, roasters must face the complicated dance of city approvals, permits, and the complexity of purchasing the right roaster and installing it,” said Emily McIntyre, director of operations at Catalyst Coffee Consulting.

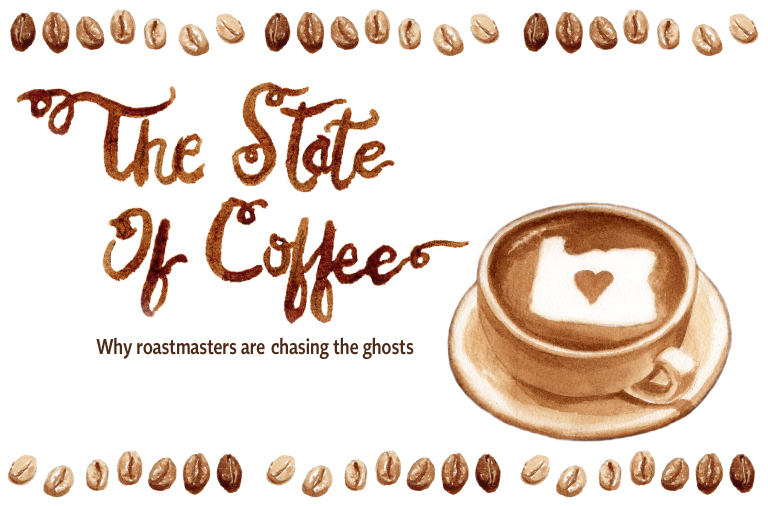

On the other end of the roasting spectrum lives Portland’s mega-roasters, such as Coffee Bean International, Boyd’s, Stumptown Coffee Roasters and Portland Roasting. Big California roasting companies have noticed Portland’s earnest bean popularity, as evidenced by Peet’s Coffee & Tea acquisition of Stumptown Coffee Roasters in the fall of 2015 and Groundwork Coffee Company, a Los Angeles-based organic roaster, which acquired Kobos Coffee, a 43-year-old Portland micro-roaster, in the spring of 2016.

These large roasters dominate the specialty scene by churning out impressive volumes of roasted beans while upholding the integrity of their nuanced roasting profiles. One such example is Portland Roasting. Nathanael May, director of coffee at Portland Roasting, said by year’s end it will have roasted almost 2 million pounds of beans with no leftovers—it sells all the beans it orders.

May travels the world in search of the perfect green bean, knowing what flavor profile he needs to bring back to Portland Roasting. He drinks about eight cups of coffee a day, which nets to forty cups a week. That number doesn’t consider that he also cups between 300 to 400 tastes a week.

Large or small roaster, they all have concerns with the supply chain, roasting exactitudes and, more than anything, satisfying customers. Consumers vote by spending their coffee dollars.

Back in downtown Bend at Thump Coffee Roasters, Grover stood near his new Loring roaster, a machine caught between steampunk cool and an Elon Musk space capsule. Wide, polished stainless steel pipes stretched to the high ceiling. At the tall cupping table, Grover showed me how to “break the crust,” how to swirl and take a quick slurp. The coffee coated my entire mouth. His slurp sounded like a power vacuum. In the six roasted coffees cupped that day, highlights included the woodsy notes of a Sumatra, a “sessions coffee” (perfect for an afternoon think tank) from Colombia and a fruity Ethiopian bean.

You may expect trade secrets and stolen blend recipes. Change, however, hits the coffee scene straight in the heart. The competition elevates the professionalism and seriousness of the roasting. What worked one day won’t work the next in ghost-chasing. “There may have been non-compete contracts a few years ago, but we all know that coffee blends are so particular to the roaster, equipment and sourced bean,” May said. “We all believe strongly that good coffee benefits everyone. Oregon coffee is a thing. Drink what you like.”

Thanks for your viewpoint Chris! You sound like someone who knows coffee!

Apparently can’t correct my typo. Lol

Interesting article though I the exception to the description of dark roast coffee being burnt and less complex, tasting of the roasting and not the beans. Plenty of quality coffee can stand up to a dark roast while I’ve tasted plenty of medium roast coffee, from reputable roasters, that tasted like sewage water. I would also point out that the list of recommended roasters is rather thin. The author lists roasters who have a co-op deal but there are still dozens, such as blue kangaroo, which roast their own. I would probably also mention specially coffee houses, such as Barista, serving and selling beans from small roasters. And if anyone really wants to geek out about coffee, I recommend reading Uncommon Grounds. It’s about 700 pages of coffee history and is quite an enjoyable read. Plus, knock Starbucks and Peet’s all you want folks, but they’re the reason we aren’t all drinking muddy, 24 hour diner coffee from Brazilian robusta. Granted, I’m going to stick with the independent, local folks when I can.