written by Bob Woodward with Laurel Bennett

To the casual beer enthusiast—aren’t we all?—the modern culture of hip brewpubs across Oregon serving some of the world’s best craft beers appears to be a relatively recent phenomenon led by such brewers as Ninkasi Brewing in Eugene, Deschutes Brewery in Bend, Widmer Brothers Brewing in Portland and the ubiquitous McMenamins establishments.

Today Oregon is at the vanguard for craft brewing. The state counts more than ninety breweries, leads the nation in microbeer drinkers, has one of two colleges in the country that condones brewing beer as an academic pursuit, displays a trophy case with too many top medals at the Great American Beer Festival to mention and is the second leading hops producer in the country. Recently, even while the economy has been contracting, craft brewing in Oregon has been expanding. As Oregonians strive for a locally driven food model, the state has become the largest commercial market for locally crafted beers. In 2009 alone, the state added ten new breweries.

While today’s aficionados drink in the benefits of this trend, each sip of this finely brewed culture in Oregon has been more than 150 years in the making.

The preceding century and a half was a hell of a fight.

Oregon’s first Brewmasters: Henry Saxer and Henry Weinhard create Oregon beer

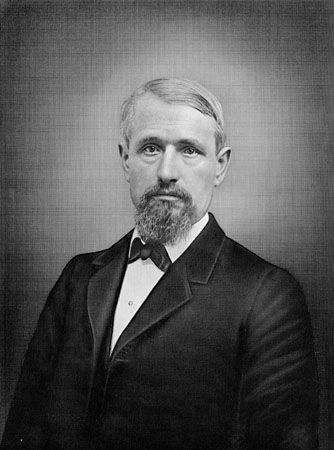

Oregon’s brewing fairy tale begins a long time ago in the loose confederation of states now known as Germany. Henry Saxer, a German immigrant, was first to the trade in the Oregon Territory, establishing Liberty Brewery in Portland in 1852. But it was his successor, Henry Weinhard, who would become the icon of Oregon beer for the next hundred years.

The same year that Saxer opened Liberty Brewery, the 22-year-old Weinhard, had just arrived in America by way of Ellis Island. Had the French been precisely 34 years more punctual in their gifting of the Statue of Liberty, the young German might have envisioned a bottle of Henry Weinhard’s beer, instead of a torch, atop Lady Luck’s outstretched arm.

Born in the Kingdom of Württemberg and apprenticed to the brewing trade in Stuttgart, Weinhard, in 1852, emigrated into America’s political foreplay of the Civil War. New York City was no civilized environment in which to ply his brewing skills. Weinhard began brewing his way westward, refining his craft along the way—first in Philadelphia, then Cleveland and finally out to Fort Vancouver, Washington.

“What Widmer and BridgePort and the rest brought to the scene was that most blessed of all benedictions: fresh ale, brewed right there right now.”

— Former Oregonian columnist, Jonathan Nicholas

The Pacific Northwest must have appeared to Weinhard as a missive sent from an all-knowing all-loving, all-brewing deity. Farmers were already growing hops in the verdant valleys of the Oregon Territory, and a thirsty throng of hearty dock workers, lumbermen and laborers lived in nearby Portland, where the only brewer in town was fellow German, Henry Saxer. Weinhard crossed the Columbia to Portland in 1855 and partnered with George Bottler to have a go at competing with Saxer.

Historical accounts say that Weinhard was disappointed with the growth of the operations and retreated to the Columbia Brewery at Fort Vancouver. Shortly thereafter, Weinhard returned to Portland with more cash and a bolder strategy—to buy out his former partner and Saxer to become the local monopoly on beer. Bold plans begat bold results.

Soon Weinhard was exporting beer to Asia and across the States. By 1875, his production had grown to more than 40,000 barrels from just 2,000 when he re-acquired his brewery.

The Bonnet Brigade: Pre-prohibition

While Weinhard was busy making the Pacific Northwest hospitable for beer drinkers, women with resolve in their bonnets were plotting countermeasures. In an 1883 meeting at Portland’s First M.E. Church, just blocks away from Weinhard’s brewing empire on Burnside Avenue, pious prohibitionists-to-be were organizing what would become the Oregon Woman’s Christian Temperance Union. They took heart in the words of the guest speaker, Frances E. Willard, the president of the national chapter of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union:

Years from now, when your conventions shall be deemed great events, and your anniversaries shall bring together its hundreds of thousands, you will look back to these words and thoughts and say, ‘those women struck the keynote of success.’

(Twenty Eventful Years of the Oregon’s Woman’s Christian Temperance Union; Gotshall Printing Company, 1904)

If brewers, contemporary and past, could wipe any day from history, it would undoubtedly be this one. That day, motivated by vocation and now strengthened by organization, women from all parts of the state rushed forth from the pews of the Taylor Street church under the banner of the Oregon Woman’s Christian Temperance Union—a crack outfit that would soon deliver alcohol’s kill-vehicle: Prohibition.

The Temperance Union’s self-described state song, sent its soldiers across the state with this tender tune:

A temperance state we yet shall call it, Oregon—land of martyr’s [sic] tears. Oregon, saved for God and country, shall banish saloons a thousand years.

Meanwhile Henry Weinhard was establishing himself as a formidable man of business with a civic mind. His operations were expanding and he had become a patron of Portland. Outside of Portland, the Temperance troops were running counties dry while installing water fountains, obviating the excuse of the menfolk who needed to duck into the saloon “just for a drink of water.”

In 1888, perhaps as a futile mockery of the encroaching prohibitionists, Weinhard offered to pump beer into the Skidmore Fountain, on its opening day, a stunt for which he is well remembered today. City officials politely declined. The Skidmore Fountain stands today at SW Ankeny and First Streets.

Oregon, we’re taught, is a state of pioneers. It embraces progressive technology, progressive thought, progressive lifestyles and progressive politics. To the detriment of brewers and the bewilderment of their consumers, Oregon raced into prohibition in 1915—smack dab in the middle of a period known as the Progressive Era. Oregon’s prohibition would begin four years before the national Prohibition launched with a capital P.

Prohibition for the full country began in 1919, gave rise to black markets, bootlegging, glorified gangsters and even some teetotaling. In a young and independent America, the 18th Amendment of Prohibition was not long lived. For ensuing years, brewers turned out soda and specialty drinks to stay afloat. The cash crop hop growers in Oregon leveraged other farming operations but continued to grow and sell hops for medicinal elixirs.

To survive Prohibition, Weinhard’s Brewery merged with Portland Brewing Company’s Arnold Blitz in 1928, eventually making Blitz-Weinhard beer. Henry’s 12th Street Tavern between Burnside and Couch streets in northwest Portland now resides where the iconic brewery once stood.

Modern presidential pundits point to the New Deal and negotiating a World War as F.D.R.’s greatest feats. Many Oregonians—especially those who have read this far—might argue, however, that his most influential legacy was the repeal of Prohibition in 1932 and these words: “I think this would be a good time for a beer.”

Making of the Oregon Brewpub Culture

Over the next fifty years, the brewing industry staggered to its feet again, but today’s variety of craft beers and brewpubs were still years off.

Portlander and longtime Horse Brass Pub owner, Don Younger, recalls the scene. “Five breweries were the players: Blitz Weinhard, Olympia, Rainier, Lucky Lager and Heidelberg,” Younger says. “All bars had only one draught. All drinkers were fiercely brand loyal. And all swore their beer was superior. Looking back now, I’m sure if I tasted them all side by side, I wouldn’t be able to tell the difference. It was very primitive. No wine, no windows—it was horrible. It was dirty and rough around the edges.”

By the 1970s, a critical shift in Oregon culture laid the foundation for the ensuing decades of growth in the industry—provincialism. Pub owners and publicans collectively gave the finger to the massive megabrewers while promoting locally made lagers, ales, bitters and stouts.

According to modern legend, the craft beer, or microbeer, brewing movement has its origins in Great Britain where, in the early 1970s, younger pub owners began canceling long-standing contracts with megabreweries and started brewing their own. Their incentive was to provide their patrons with tastier beers and a wider variety.

That same spirit moved a small number of Portland beer aficionados, who, in the late ‘70s, set a course to change the way beer was produced and dispensed in and around Portland. Unlike the burgeoning microbrewing culture in California and Washington, the Portland movement centered on comfortable public houses. “People began to snub generic, processed and multinational corporate products in favor of local handcrafted creations,” notes McMenemins Brewery historian Tim Hills.

Portland had always been a town with great bars and pubs, Jim Parker of the Oregon Brewers Guild, observes. Now those pubs and bars were serving customers brews of their own creation, or those of other local craft brewers.

In 1979, the first true Portland microbrew pub came into being—The Cartwright on Hawthorne Avenue. It lasted for only three years, just long enough to whet the appetite of local beer lovers for handcrafted brews. Soon more microbrew pubs like The Fulton, BridgePort, Produce Row, Portland Brewing’s Taproom, Captain Ankeny’s Well, Rubin’s Gulch Café, Widmer’s Taproom and Horse Brass Pub were serving pints that were brewed elsewhere.

Brewers and beer-drinkers of yore would note 1883—the year that the Temperance bees buzzed out of their meeting and fomented prohibition—as one of the worst years of the century. If barley and hops had sustained their lives a hundred years more, they would claim 1985 as one of the best years for beer culture in Oregon.

It wasn’t until 1985 that a small motivated group of brewers pushed new laws through the Oregon Legislature that allowed the combination of brewing and retail sales, a critical piece of law that shapes today’s industry. “It was illegal to have retail and manufacturing on the same premise,” notes Brian McMenamin, who with his brother, Michael, owns the legendary McMenamins chain of brewpubs and lodging facilities. “So it was impossible to make beer and sell it in a restaurant that was on the same premises.”

The McMenamin brothers, together with a group of Portland-area brewers including: Richard and Nancy Ponzi of Columbia River Brewing (now BridgePort Brewing); Art Larrance and Fred Bowman of Portland Brewing; Kurt and Rob Widmer, of Widmer Brothers Brewing, all decided to write a bill that would change the law in Oregon.

“Our bill kept getting killed and killed and killed,” Mike McMenamin recalls. “Finally it was attached to a bill to allow Coors to sell their beer in Oregon. We thought this was the death knell for us, but, to our amazement, the bill cruised through.”

The law had the effect of manifest destiny across Oregon with innovation and collaboration at its heart. New brewp sprang up and the brewing craft was once again in high demand in Oregon. In the ensuing years, stouts sprouted in Newport, porters surfaced in Portland and, soon, pale ales took on prominence in Bend.

Rob Widmer recalls the genesis for one of Oregon’s food groups, Widmer Hefeweisen, with this story: “We started with an Altbier, which is still a beer-geek’s favorite, but was a bit too much for most beer drinkers at the time. We needed something more approachable and wanted to do it in a German style, which was the niche we were carving out. We knew the Germans brewed a blond wheat beer, and we set out to make our own using our Altbier yeast.”

The result was a cloudy unfiltered Widmer Hefeweizen that was puzzling to the average consumer. Fear of the unknown lay between that murkiness and the beer’s commercial success.

“But one night, when the Hefeweizen was new at the Dublin Pub, the owner, Carl Simpson, said to me, ‘Watch this,’”spread like wildfire through the pub and restaurant community the following morning,” Widmer summons triumphantly.

“In the mid-’80s, Portland already had a rich pub culture…,” former Oregonian columnist, Jonathan Nicholas, observes. “What Widmer and BridgePort and the rest brought to the scene was that most blessed of all benedictions: fresh ale, brewed right there right now. Overnight, Portland became the beer city in America. And now guys in San Diego sit poolside, idly twirl the parasols in their girlie lagers, and gaze out across the ocean wondering how much fun it might be to live, and drink beer, in Portland.”

Such was the call of Californian, Gary Fish, who encountered the right environment in Bend in 1988 to execute his brewpub concept, Deschutes Public House. The small sleepy mountain town was just beginning to shake off a sluggish ‘80s economy. “People didn’t know what to make of us,” says Fish of the first patrons at the Bend brewpub. “The reason why this product took hold in Oregon is the independent spirit of Oregonians and creative, innovative brewers.”

Legislation and a growing provincialism for locally crafted beers soon turned the microbrewer of Mirror Pond Pale Ale and Black Butte Porter in obscure Bend, Oregon into a macro success, as the state’s largest brewer by barrel count.

“I was lucky that we could hire John Harris from McMenamins,” says Fish. “He was able to call them and ask questions, and that was a terrific benefit for us.” Breweries now number more than ninety in Oregon, with ten new brewpubs arriving in 2009 alone.

Oregon Beer by the Numbers

Total economic impact from the beer industry on Oregon’s economy: $2.25 billion.

Jobs created by Oregon breweries over the last five years: 2,300.

Oregon-brewed beer consumed in Oregon over the last five years: 12% up from 9.9%.

Oregon is the second largest producer of craft beer in the U.S.

About 12% of the total beer consumed in Oregon in 2008 was Oregon craft beer- the highest percentage of local craft beer consumption in the country.

National average for total craft beer consumption by volume: 4%.

Oregon is the second largest hop-growing state in the country.

Current brewing companies in Oregon: 73, operating 96 brewing facilities

Breweries operating in Portland: 30, more than any other city in the world.

Largest craft brewing market in the US: Portland metro area.

Source: Oregon Brewers Guild