At first it doesn’t sound like jazz. The Sam Howard Band is playing “The Astoria Waltz” at The Blue Monk’s Sunday showcase with such a high lonesome sound, it could almost be country. The rhythm is too loose, though, the melody elastic. Later, they start rocking, but the driving bass line gradually goes off the rails. “Bog Stompin” might be blues, with its swampy feel, but it too wrinkles and twists into unfamiliar territory.

Not bluegrass, blues or rock, this is Portland’s new Indie jazz scene. And though Howard and his mates dress like a garage band, these highly skilled and imaginative under-30 musicians are still making jazz—an updated version suited to twenty-first century Portland.

They aren’t alone. Jazz in the Rose City is blossoming with youthful innovation these days in a Pacific Northwestern cult fueled by creativity. While expressing the independent spirit of Oregon, this emerging jazz culture also remains connected to the past.

Indie jazz is only one of many styles played nightly in the city’s nightclubs, restaurants and concert halls. Every week, retro swing, avant garde and many varieties of mainstream and contemporary jazz fill the air, from more than one hundred active artists. Despite its size and diversity, there’s a sense of community among the musicians that—added to the other attractions of the city—has made Portland a mecca for jazz experimentation.

“When I moved here, I was impressed by the community nature of the music,” recalls Darrell Grant, a pianist, composer and professor of jazz studies at Portland State University. Grant, 48, moved to Portland in 1996 from New York, where his CD, “The Black Art,” was on The New York Times list of the best jazz albums of 1994. “It’s very much an ‘all for one, one for all’ kind of feeling,” he observes.

That cooperative spirit spurred artistic freedom. “I went to hear the Alan Jones Sextet, and I heard all these individual players, with all these different sounds,” recalls Grant. “They could do anything they want, they could put everything they want all in the same music, without having to worry about it.”

An original American fusion of European, African and Native traditions, jazz has absorbed many influences in its hundred-year history. This evolution seems appropriate for a music based on improvisation, where developing an individual voice is the highest value.

Portland has nurtured a creative place for development that has laid the foundation for the next jazz generation. Grant thinks it’s due to what he calls the terroir of the place.

“In wine, they call that mix of dirt, rain, sun, wind and water that makes one vineyard’s grapes taste different from another’s, the terroir,” he says. “The territory shapes its artists, too, seeps into our tunes and our dreams, inspires us, connects us—whether we’re native or transplant.”

Youth Movement

Sam Howard, a Wyoming native and former New Yorker, finally felt free to craft his own style under the influence of the Rose City’s laid-back, easy-going camaraderie. Absent was the bother about the latest trends in New York or Los Angeles.

In fact, young Indie jazz pianist Ben Darwish sees that “create-yourself” spirit as a defining element for him and his Portland peers. “We’re doing what we want to do,” says Darwish, the winner of the 2010 American Society of Composers, Authors and Players Young Jazz Composer Award. He also leads the Afro-pop group, Commotion. “That’s one way to define Portland jazz. I don’t care about getting famous, I just want people to listen to the music.”

But it’s not simply a desire to be different that drives Portland’s Indie jazz movement. “We wanted to play music that people from our generation would want to come listen to,” says The Blue Cranes’ Reed Wallsmith. “We don’t consider ourselves just a jazz band.”

The Blue Cranes have shared the stage with rock and electronica groups, and yet they’ve also been featured at the Portland Jazz Festival, an award-winning annual event that brings the music’s biggest names to town. Beginning with the Mt. Hood Jazz Festival in 1982, the city has hosted an international festival every year.

“There’s a certain vibe to this city,” says Andrew Oliver, who plays keyboard with The Sam Howard Band. “And that independent spirit is reflected in the music.” Oliver studied in New Orleans before returning to the Rose City after hurricane Katrina. That event also blew in young saxophonist Devin Phillips, whose Portland-based groups have twice toured West Africa with Oliver on piano.

“Take Dan Duvall,” says Oliver, referring to the young guitarist who books an eclectic weekly series at The Crow Bar. “Everything he does sounds like Portland to me. He brings whatever he wants, he doesn’t care where it comes from.”

That freedom allows the players to express themselves across multiple styles as well. Oliver, a winner of the American Society of Composers, Authors and Players Young Jazz Composer Award in 2011, leads several groups of his own, including an improvising hard-bop ensemble, a West African jazz fusion group, and the oldtimey Bridgetown Sextet.

As progressive as the city’s new voices may be, they are building out from the hopping jazz culture of Portland’s legendary Williams Avenue scene.

Williams Avenue

It all started in the early 1940s on Williams Avenue, in the heart of the city’s African-American neighborhood. Bebop was new, and jazz, blues and R&B flourished, while races mixed in the audience and on the bandstand.

“You could stand in the middle of the avenue and look up Williams past the chili parlors, past the barbecue joints, the beauty salons, all the way to Broadway, and see hundreds of people dressed up as if they were going to a fashion show,” writes historian Robert Dietsche in Jumptown: The Golden Years of Portland Jazz . “It could be four in the morning; it didn’t matter … There must have been more than ten clubs in as many blocks, not counting the ones in the surrounding area.”

Clubs on Williams Avenue offered touring jazz players a chance to stretch out and express themselves after playing dances. Louis Armstrong once dropped in to the Dude Ranch (on the corner of Broadway and Weidler streets), and nearly the whole Count Basie Band showed up one August night a couple weeks after the end of WWII, according to Dietsche’s Jumptown. Most representative of the Williams Avenue’s cutting edge scene was the appearance at the Dude Ranch in 1945 of Norman Granz’s historic, racially integrated Jazz at the Philharmonic show, which included pianist Thelonious Monk.

One of the venues that helped bind the jazz community in those days was James Benton’s converted garage on Williams Avenue and Savier Street, where jam sessions started in the afternoons and continued long after the gigs were over.

“I put in a little three-hole golf course out back, and guys would play a penny a hole,” Benton remembers. “Out-of-town musicians and their wives would come by, too. I’d always have a pot of beans cooking, and if a musician was down on his luck, ‘Well come on by man, get something to eat, sit in if you feel like it.’”

Benton is still performing under the name, Sweet Baby James, with Louis Pain, who played Hammond organ with the Paul De Lay Blues Band for more than a decade. Young drummer, Micah Cassell, often plays with them. He was with Howard’s Indie jazz band that Sunday at The Blue Monk.

Mel Brown’s Network

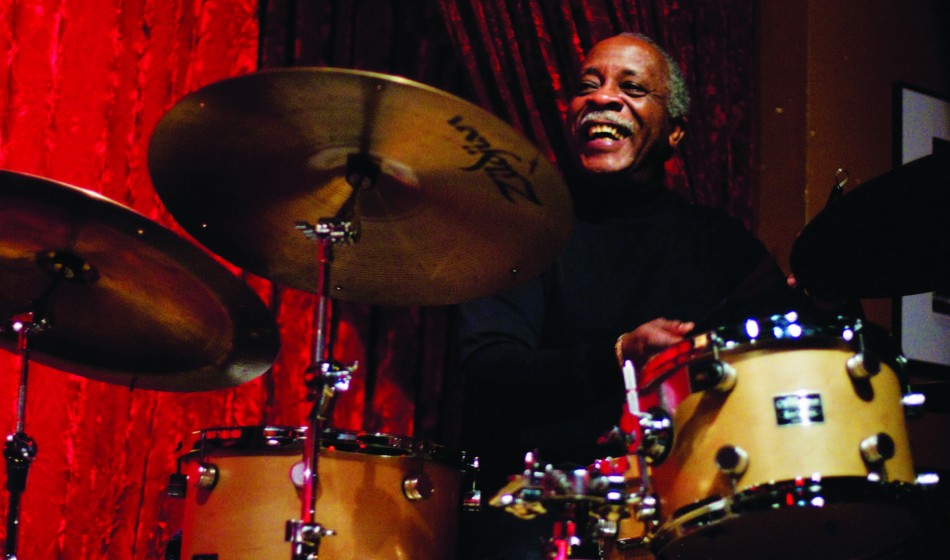

In Portland, such connections between past and future are as abundant as the links between jazz and blues. At the center of that web sits world-renown drummer Mel Brown, who got his start on Wlliams Avenue.

“At that time, Bobby Bradford and Cleve Williams would wait for me after school, and they’d show me how to set up certain figures with the Walter Bridges Big Band,” recalls Brown, 67. “That kind of teaching of younger musicians was what everybody did because they were helped that way themselves.”

Brown joined Martha and the Vandellas in the late ’60s, then went on to a decade in the Motown stable, touring with the Temptations and later, Diana Ross. But his first love was jazz.

So he returned to jazz and his hometown in 1973 and today leads five different groups every week. On Tuesdays, Brown’s hard-bop septet appears at Jimmy Mak’s, where the stage is named for him. A frequent sub in the alto chair of that band is young phenom, John Nastos. The sax player has also written arrangements for a new album by the Art Abrams Big Band, whose members’ ages range from their 20s and into their 70s.

Wednesdays at the same location, Brown’s mainstream quartet includes guitarist Dan Balmer, 52, another Portland native with a national reputation who leads his own group at Jimmy Mak’s on Mondays. On piano with Brown on Wednesdays is Tony Pacini, a jazz icon himself and the host of a weekly show on public radio station KMHD (89.1 FM). With an audience among fulltime jazz stations second only to WGBO in New York City, KMHD is another reason the Portland scene remains so strong.

Passing It On

One of Brown’s frequent collaborators over the years has been trumpeter and composer Thara Memory, 64, a native of Eatonville, Florida. An acclaimed jazz educator today, he arrived in town in the ’70s on tour with R&B star, Joe Tex. Among Memory’s former students is young bassist and singer Esperanza Spalding, winner of a 2011 Grammy Award for Best New Artist. When she returns to her hometown, it’s often to assist Memory with his youth bands.

“I wish I had more time to understudy with Thara,” says Spalding, who credits her training in Portland for her success today. “It doesn’t come from nowhere. I left Portland with a certain confidence that I really had something to offer.

” What helped the most, Spalding says, was the on-the-job training her Portland mentors offered. “That’s what really gets you to a high level of musicianship.”

In the early 1980s, Brown himself pulled two young musicians out of Mt. Hood Community College to tour with Diana Ross—pianist George Mitchell, who still works with the former Supremes diva, and bassist Phil Baker, who today anchors the internationally touring band, Pink Martini. Baker has written a number of tunes for the famed Tom Grant Band, too.

Tom Grant, whose father owned a record store on Williams Avenue, was a smooth jazz pioneer in the ’80s. Earlier, he was in on the development of jazz fusion with Miles Davis’ drummer, Tony Williams. Today, Grant, a masterful mainstream pianist as well, leads a Sunday jam session in Vancouver and plays four nights a week at The Oswego Lake House with a variety of singers.

Guitarist Balmer first garnered attention with the Tom Grant Band. Later, he helped train some of the younger generation’s top players, including guitarist Mike Pardew, 31, who performs weekends at Nel Centro Restaurant. By day, Pardew is busy teaching the next generation of eager acolytes at his Credenza Academy—the pipeline of new talent. “The more I travel, the more I realize this is the only place to live,” says Baker. “There’s such diversity, so many interesting things to play, and so many great musicians. The bench is very deep for each instrument here.”

The talent is deep, yet drummers often seem to be at the heart of it.

Witness drummer Ron Steen, 59, who caught the tail end of those Williams Avenue jam sessions before the neighborhood was bulldozed for the I-5 freeway and Memorial Coliseum. Since then, he has led countless sessions of his own, where a number of today’s successful artists got their start, including pop jazz star Chris Botti. Steen, who toured with several big names in his younger days, has been leading jam sessions continuously in Portland for twenty-seven years.

“He plucked me out of the little town of Mill City where I was teaching high school, and I ended up going to New York with Jim Pepper,” Grant recalls. With Portland-raised saxophonist Pepper, a member of the Caw and Creek tribes, Grant recorded “Witchi-Tai-To,” a song covered by both pop and jazz acts. A colorful folk hero and international star, the late Pepper is celebrated for his fierce integrity and fusion of Native American music with jazz. Many musicians still cite him as being the epitome of the independent

spirit that animates the Portland scene.

Drummer, composer and educator Alan Jones, 48, another leader today, once studied with Brown. Now, every Thursday, he leads a group of student musicians himself. He learned his craft from legendary bassist Leroy Vinnegar, the “Father of the Walking Bass,” who came to Portland from Los Angeles in 1986. Jones dedicated an album to him after the bassist’s death in 1999. The compositions

on Jones’ sextet’s latest CD, “Climbing,” reflect the Oregon’s terroir as well as its jazz history.

“This music was composed to give expression to the uniqueness and the natural gifts we have here in the Pacific Northwest,” says Jones, a rock climbing enthusiast and outdoorsman.

Not Just The Coffee

That adventurous connection to the natural world is another part of what makes Portland’s jazz scene distinct. Dissertations have been written about connections between the landscape and compositions by the internationally acclaimed group, Oregon, whose co-founders, Glen Moore and Ralph Towner, hail from Milwaukie and Bend, respectively.

One of Moore’s frequent collaborators, is Grammy-nominated singer Nancy King. Her career has surely been defined by an independent spirit and refusal to compromise for commercial success.

“Nancy’s not acting like a diva,” says her pianist Steve Christofferson, who recorded an album with her and the Metropole Orchestra of the Netherlands in 1999. “Nancy is a diva. She doesn’t like to be told what to do.”

Maybe because it’s located far from the pressures of media centers, Portland seems to encourage performers to be themselves. Pianist Bill Beach, for instance, who built a reputation as a top local bebop player, has, in the past decade, transformed himself into a singer and composer in the samba and bossa nova styles. He went to Rio de Janiero, Brazil, studied the music and the language, then

made it his own.

Far from media, but connected to the world, Portland musicians have developed distinctive voices in Portland, then taken them abroad. Notably guitarist John Stowell, a former partner of world-renowned Portland bassist David Friesen, takes an advanced approach to harmony. His style has made him a highly demanded performer and teacher from Berlin to Buenos Aires. Stowell always returns to the Rose City.

“There’s something brewing here,” observes young pianist Oliver. “There’s a collaborative spirit, groups are hanging out and talking … People feel the younger guys are up to the same thing.”

Even if at first listen it doesn’t quite sound like jazz of the past, this Portland Indie jazz revival has deep roots in a place where landscape and community have nurtured an independent spirit. Nobody’s getting rich. Even so, since the Williams Avenue scene of the ’40s, the new era of jazz in the city is ushering in an independent sound with the feel of a golden age.