This is a story about taking time, slowing down and changing your life on Oregon’s back roads. It’s about stopping at restaurants, shops, roadside markers and parks you’d never consider if you were just blowing past in a minivan. In the end, the motorcycle is a vehicle for change unlike any other.

I once owned a motorcycle, but our relationship was immature and hell-bent. It was college, and we were more interested in the surface, looks and mutual abuse. That was more than two decades ago. The risk parameters seemed fuzzier, friendlier. Tires, I’m sure, had more traction then. They went faster and seemed more stable at higher speeds. Weather conditions were never a factor unless they prevented more forward progress than sideways progress. Motorcycles had wings, and they were magical.

At some point, though, I had a not-so-magical landing that led to a long estrangement from and resentment of motorcycles.

When the topic of rekindling my unsuccessful relationship with motorcycles innocently arose one day, my wife most sensibly laid down the over-my-dead-body threat. “Think about your kids! Think about me,” she said.

I did, and then enrolled in a motorcycle safety class that would allow me to become a more sensitive partner in my relationship (with motorcycles), a more responsible husband and father, and ultimately join the Oregon Discovery Rally, a three-day ride into the bosom of beauty.

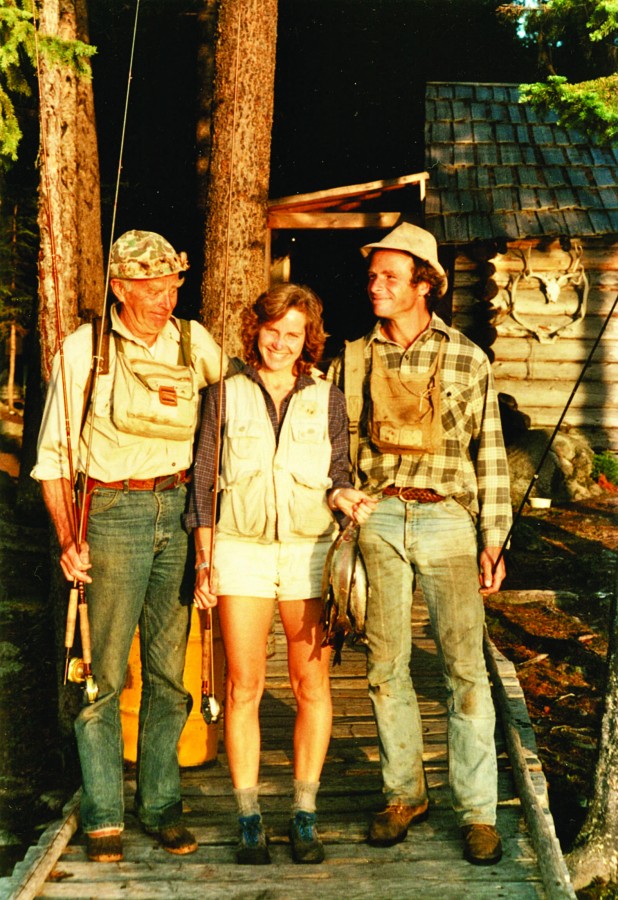

Through the kindness and blind faith of Billy and Stacie Benedict of Oregon Dual Sport Rentals & Adventures and gear guru Brian Price of Atomic Moto, I was able to procure a bike, get protective gear and learn from experienced riders who would soften the blow at home.

Dual sport bikes are hybrid bipolar innovations that are comfortable on paved roads but yearn for gravel on a mountain pass, sand in a desert crossing or a combination thereof. They are designed to take you from the relative safety of civilization to something a little more bumpy, uncivilized—adventure.

“When you drive a car, it’s like watching a movie,” Stacie explained. “When you ride a motorcycle, it’s like starring in a movie.”

These bikes are much quieter and lighter than Harley Davidsons and, frankly, many of their operators, too. They don’t seek groups of twenty for recognition, are rarely found in meaningful numbers in Sturgis, South Dakota and seldom host an intentionally-sleeveless rider.

With the exception of a few events, dual sport riders are mostly found in pairs, riding and camping along the path of adventure. The Discovery Rally is no exception—an excursion into the unknown. This event began in 2006, when Scott and Madelyn Russell of European Motorcycles of Western Oregon brought together their passion and a few riders in a state with enough dirt, gravel and stunning vistas to make for endless possibilities.

The rally involves camping, navigation, maps (lots of maps), true self-assessment, calculated risks, a balance of the mechanical and the romantic and, at the end of the day, bathing in the cool riffles of the Wallowa River.

The candidates for rides range from winding paved roads to rugged off-roads. Some bikers were keen on dirt roads that don’t show up on most maps. Others were more content with scenery, greenery and pavement.

Day 1 – Rattlesnake

Bikers had been straggling in all night, making breakfast our first quorum— all of those who were going to be in camp were now in camp. After the unexpected delicacies of French toast with mascarpone cheese and blackberries, maps became the feast. Maps in this community are not just the holy grail but an ongoing obsession, even one-upmanship.

“There’s a gravel road that goes through there, but it’s not on your map. Wait,” said one rider, producing a bigger map. A chorus of envious ahhs can’t be suppressed amid such glorious manifestations. “Here,” he pointed to a follicle on his map. “Here is a gravel road that should be there unless it’s been washed out.”

It was a 40-degree September morning in northeastern Oregon and truly my second day back on a motorcycle since college, third if you count my introductory ride with Billy and Stacie. (You really should count that, because we all lived a lifetime in that eventful day. It’s really too much, too early to go into here, so I’ve written an addendum that you can find here.)

Maps are almost irrelevant to third-day riders. I’m a follower, a liability to most other riders, myself and perhaps to oncoming traffic, too. One group decides to head to Troy, a tiny fishing enclave at the confluence of the Grande Ronde and Wenaha rivers, down a long gravel pitch that may or may not have fallen trees and may or may not be awfully rutted from a washout. Another is pointing to Enterprise and Joseph and in the direction of the unincorporated town of Imnaha. A twenty-four mile gravel grade picks up in Imnaha and climbs steeply to the southwestern end of Hells Canyon. A third ride bantered about was the “Rattlesnake Grade,” a ten-mile descent into the Grande Ronde River canyon on a paved road that, on a map, appears to have been poured by a happy drunk.

Billy and Stacie had skillfully shepherded me the 320 miles out to Minam and in one piece, so I was sucking their wheels like a needy calf on a teat. It’s into the belly of the snake we go. The shortest distance between two points is a straight line. It’s also the most predictable and prosaic distance. Lines, straight lines, are boring cousins to backroads. Leave them for long-haul truck operators and multi-tasking minivan drivers. Had Euclid owned a dual sport bike, geometry would look less like a hypotenuse and more like the rambling Rattlesnake Grade.

On most maps, this coil of a road is called Highway 3. At the Washington border, it becomes Highway 129 and runs straight up to the Idaho-Washington border towns of Lewiston and Clarkston. About forty miles north of Enterprise is the head of the Rattlesnake Grade. We pulled off the road to gape into its maws.

Ten non-linear miles and 3,000 feet below the rim of the canyon lay the Grande Ronde River. Before that were one hundred tight switchbacks and sweeping turns with little room for error. Take the turn too wide and you’d be as free as a butterfly, aloft thousands of feet above the river. Take the hairpin too tight and there would be a gleaming white cross to commemorate your head-on collision with whatever was coming the other way.

Stacie tactfully reminded me, “Look up the road, go up the road.” I repeated it in the privacy of my helmet a dozen times. Look up the road, go up the road. A common error among novice bikers is navigating turns as if they’re still on four wheels—eyes glued to the vehicle in front of them, not leaning into the turn. Motorcyclists, on the contrary, are taught to look through the turn, essentially focusing on where they want to go, not what’s directly in front of them.

Look up the road, go up the road. Somewhere between the eyes and the inner ear, this process helps execute a continuous arc of lean and speed. At its most extreme execution in a hairpin turn, the motorcycle is going one direction while the rider’s head is spun around the opposite way. The whole process feels unnatural and arrogant at first, like ignoring the outstretched hand of congratulations to get to the trophy.

The speed slows coming into a turn and the bike stands more erect. The helmet, head and eyes—all one—slowly turn to look through the turn, around the corner, up the road. Gradually your body leans into the turn, forming the beginning of a graceful arc. At the apex of the turn, you gently roll on the accelerator and descend into the elongating space beneath you. The wheel base spreads farther apart while you slide deeper between. Gently the speed increases through the tail of the turn, eventually standing the bike up again. Left. Right. Left. Right. It’s a powerful and mezmerizing thrill riding down the canyon, where Boggan’s Oasis Restaurant makes its palliative milkshakes.

On the first ride of the Oregon Discovery Tour, I had completed one of the top motorcycle rides in the state. Look up the road, go up the road. This relationship felt more mature.

Back in camp, Scott, Madelyn and their 14-year-old son, Kendrick, were grilling steaks, baking potatoes and serving them with a fresh spinach salad. Stories of the day’s rides were already wafting over the campfire, weaving in and out of circles of riders—Larry and Beverly from Indiana; Monica and Oliver from Luzern, Switzerland; Reuben from Puebla, Mexico; Hans, Lindy and Bob from Eugene; Wayne from Lincoln City—and falling onto filaments along illuminated maps.

Day 2 – Imnaha and Hat Point

At breakfast, tales from those who rode the prior day to Hat Point—a gravel grade that vaults out of a small unincorporated town called Imnaha to the southern lip of Hells Canyon—were the talk. Maps came out to confirm the claims.

“It’s not an easy ride,” one rider confirmed. “There’s more than twenty miles of gravel to get to the top, but it’s spectacular once you do,” said another. “You can always turn around at Imnaha, and it’s still a great ride,” said a third. Between our camp at Minam State Park and Hat Point lay ninety miles of mixed terrain. There are thirty-seven miles of pastoral paved riding southeast to Joseph, the peaks of the Wallowas to the south.

Highway 350 heads due east out of Joseph then turns northeast along the Imnaha River basin. This stretch of road is a car-sick carnival to most drivers, with its constant turns, its back and forth. For our lot, though, it’s a magical gulley for carving turns as effortlessly as a ski in fresh snow.

Along this river basin, the Nez Perce, led by the famed Chief Joseph and his son in the 1800s, roamed this area for centuries, fishing and hunting buffalo. They were mischaracterized by the French as having their noses pierced, or nez perce , and were later chased from their homeland by the U.S. Army led by General Oliver Howard.

The headwaters of the Imnaha River are in the Eagle Cap Wilderness in the Wallowas. The river runs northeast for seventy-three miles to its confluence with the Snake River then north to the Salmon and Columbia rivers. These river basins comprise the ancestral areas of the Nez Perce. Along the Imnaha River basin, there are no towns until you trip over the unincorporated Imnaha.

Imnaha is a tiny enclave on the skirt of Hells Canyon. Aside from a few ranches and houses, the three pillars of civilized society—state, religion and the state religion—are represented by a thirteen-foot-by-sixteen-foot U.S. Post Office, a church that serves as its school, and the Imnaha Tavern, where rattlesnake slayers are rewarded and dead wolves are celebrated.

One thing you can count on when riding a motorcycle is a challenge. There are questions of comfort, balance, steering through turns and blind corners. There are other elements—wind, sand, ice, water, gravel, grade, a low hanging sun and your own mental state and ability. Many of these are negligible in a minivan milieu but become prominent in the motorbike landscape.

The climb out of Imnaha is a narrow gravel road that gains elevation quickly. Many of these challenges immediately present themselves for inspection. The only true trail riding I’ve done was my literal crash course the prior week with Billy and Stacie. As we rode through the Central Oregon dusty backcountry on the way to the wholly unimpressive Hole in the Ground that day, we put about an eighth of a mile between us to improve our visibility. Even so, we rode through a light fog of dirt, but slowly.

As we rode, the dirt became sand and the sand became lighter than air. Riding on gravel is a different skill set than road riding. Visibility and speed decrease, as do traction and control. Often you’ll see a rider coming down a trail while standing on his foot pedals. It’s not cool for cool’s sake. The prevalent theory is that by standing, you take the weight off the back of the bike to prevent fishtailing while learning to grip the throttle lightly to gently feather it through floury terrain.

As we rode to Hole in the Ground the week before, the high desert dirt increasingly became like beach biking. Ruts left from prior rains were now filled with fine silt. Trailing Stacie by a couple hundred yards, I rode into a particularly nasty dust-up only to discover her bike on its side with Stacie strangely on her side, too. I panicked and side-crashed. A fine silt exploded in a white plume around me.

Sand is awful to ride in but a pleasure to crash in. Neither of us was hurt. From behind, Billy saw that the path ahead become increasingly dense with dust and assumed that at least one of us went down. As we set Stacie’s bike upright, Billy rode cautiously through the diaphanous curtain. Stacie was mummified in blonde sand. “Damn woman! You’re filthy!” Billy quipped.

As we had in procession to Hole in the Ground, at Hat Point we increased the spacing between our bikes and set off up the dirt road. At an average thirty miles per hour and twenty-four miles up, Hat Point was going to be a haul. As we climbed the first five miles, the views became living frescoes of rolling grass meadows—a god-view of the true blue Imnaha River thousands of feet below with dark grey scores across canyon walls marking bygone dynasties.

As absorbed as I was in ongoing motorcycle education, I was humbled by the grand vistas outside of my helmet. Few people get the time to slow down and just have a look. Fewer ever get to feel such beauty.

Farther up the road, 5,000 feet higher and much later, we crested Hat Point Road. From the looks of it, Heaven couldn’t be much farther bove Hells Canyon. If it were, it wouldn’t be much more picturesque.

An eighty-foot wooden fire lookout tower rose from a flat ridge-top clearing. Beneath it are the Snake River, Hells Canyon and, much closer, picnic tables with the best views in the American West. Atop it all in a seven-square-foot fish bowl sat Michael Oliver, a U.S. Forest Service fire spotter—his maps, a thermos, a radio and a camera his only company. In summer, he scans the horizon east to Idaho, north to Washington and Oregon beneath for smoke. That day, two fires of considerable size—9,000 and 16,000 acres—were burning across the Washington and Idaho borders. Over the course of each summer, Oliver snaps photos of ghost-like mountain goats quietly grazing below, rainbows spanning the canyon, blooming flowers under setting moons and electrical storms flashbulbing the landscape.

Somewhere back down the road is Joseph and Stein Distillery, whose whiskey was now properly aged and would make a nice fireside treat, and Terminal Gravity Brewery in Enterprise, where streamside picnic tables and IPAs would provide safe harbor for a few dirty riders.

The Road Home On the final morning of the Oregon Discovery Rally, camp broke slowly and reluctantly. Tents were rolled, clothes were stowed, coffee drained and water bottles filled. No one really wanted it to end, but most had long rides ahead of them before reaching home. Some went on to cross the entire width of Oregon, bound for the southern coast, others shot back to Portland or Eugene, while the Swiss stashed their bikes in storage until they could take up their American exploration next year.

Stacie, Billy and I headed southwest toward home. Along Highway 380 is Post, Oregon, named after a nearby post that marks the absolute geographic center of the state. An unincorporated desert town southeast of Prineville, Post doesn’t have many standing structures. One surprise, though, is the Post General Store and its oasis of milkshakes.

Outside, it’s a sagebrush scrub-land, a place that minvans roll past, air conditioning blasting, music blaring. Stepping on the brake is losing time. Time does double-speed until you arrive at your destination, ignoring all points on the map in between and the parts where Oregon is most beautiful and most alive.

I know it seems hugely optimistic, but sometimes you can change your life by changing how you travel. If you’re fortunate enough to do that, take your eyes off the bumper in front of you, slow down, look up the road and go up Oregon’s backroads.

Plan your trip

Oregon Discovery Rally

September 8-11

Central Oregon Cascades

Cost: $100

Oregon Dual Sport Rental & Adventures

oregondualsportrentalandadventures.com

Atomic Moto | Atomic-moto.com

European Motorcycles of Western Oregon

emcwor.com

Dual Sport Rides:

Crater Lake Rim

Rattlesnake Grade, northeastern Oregon

Hat Point Road, Imnaha

John Day Fossil Beds

Oregon Coast, Highway 101

Historic Columbia River Highway A ranch just east of Wallowa.

Click here for a full gallery of photos from this trip and a special collection from U.S. Forest Service fire spotter Michael Oliver.