Nearly a century ago, a deft-minded Governor Oswald West put his hand to his holster and drew out political genius rather than his pistol.

Oregon’s lava-riddled coastline has a rugged and rebellious quality, traits shared with its namesake: a man who finessed the law that made Oregon’s beaches the public property and the people’s coast.

Although Oswald West’s legacy encompasses a number of visionary accomplishments in the early 20th century, he is best known for his work in turning over the Oregon coastline to the public. And though he saved the Oregon Coast from the privatization that has pervaded many other coastal fronts, West is famous—infamous really—for how he pulled off the enormous political feat of taking public possession of hundreds of miles of the Oregon Coast.

“I know not why, but it appears that I was born to stir up trouble,” West, the ‘Father of Oregon’s Beaches,’ stated in his memoirs published in The Oregonian in 1937. “Early in life I rebelled against the established order of things, believing it to be responsible for most of the poverty and distress abroad in the land.”

West has been called a clever politician, a visionary thinker, a dynamic strategist and a crafty conservationalist who used unorthodox means to justify the end. “He was also a Democrat in a commonly Republican state, a militant Dry in a Wet state,” one historian wrote. “Although absolutely incorruptible, he was a shrewd politician with an extraordinary fine sense of drama as a part of the fitness of things.” A journalist described West as a “horse-loving, whiskey-hating, pistol-packing former governor of Oregon in one of its most colorful, tumultuous and productive eras.”

As a result of sticking to his guns, both literally and figuratively, West had great success as Oregon’s fourteenth governor, serving from 1911 to 1915. His handsome, crisp features, thin pinched lips, determined eyes and meticulously combed hair added authenticity to his reputation as a formidable opponent. More interesting is that West pushed numerous pieces of legislation through a Republican-dominated legislature. One such piece would have a lasting effect that benefits Oregon’s beach-goers today and tomorrow.

“Failing to find any other man of standing willing to enter the lists, and not wishing to give my support to some other two-by-four, I decided to throw my own hat in the ring.” — Oswald West

Oregon has 362 miles of shoreline open to the public with access points spaced approximately every three miles and attracts about 3.5 million visitors annually. Although there is a happy ending for the majorityof Oregonians and coastal visitors, this storyline could have taken numerous twists throughout the 20th century, most notably succumbing to the hands of privatization in the late 19th century.

Oregonians have historically assumed that the whole beach belonged to the public. From Native American coastal tribes to the Lewis and Clark expedition to World War II, people have been using the beach as a highway in order to travel north and south avoiding dense and difficult inland routes. The beach was not only used for foot and horseback travel, but eventually cars—even airplanes—would transport people and goods and serve as a destination for recreation.

In 1874, however, the State Land Board unwittingly triggered the impetus for what would later become West’s legacy when it sold twenty-three miles of beachfront property to private owners over the ensuing three decades. Legislators became increasingly skeptical of selling this land, acknowledging the coast as an important transportation route, and proclaimed in 1899 the thirty miles of ocean beach between low and high tide from the Columbia River to the southern border of Clatsop County as a public highway.

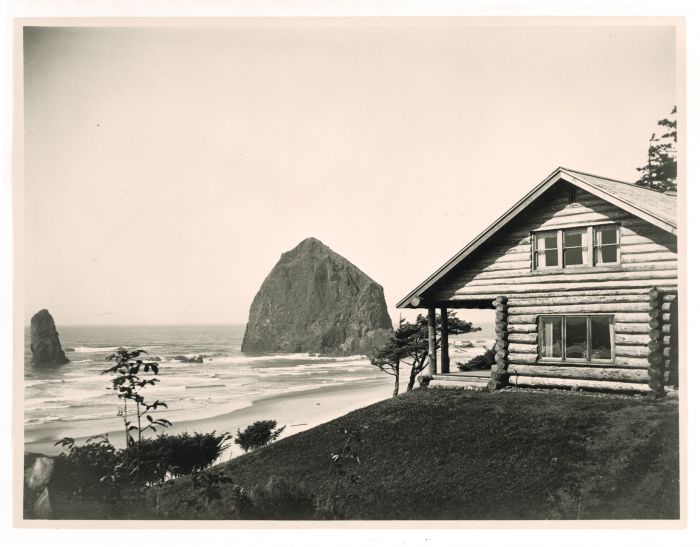

To West, who had a two-story log cabin home in Cannon Beach overlooking the iconic Haystack Rock, the privatization of coastal property did not sit well.

Born in Ontario, Canada in May 1873, West’s family emigrated to Portland when he was 4 years old. Misfortune struck when his parents, Oswald and his six brothers and sisters lost everything they owned in a hotel fire. After spending a few years in Salem, the family returned to Portland, where West attended school and drove cattle in the shadow of his hard drinking father. Although West’s formal education was halted halfway through the eighth grade, he was, in his own words, “at heart a rebel … with but little education.” The need to make a living quickly dashed his dreams of becoming a professional jockey and he began work at a bank, first as a messenger and then as a teller.

After a brief stint looking for gold in Alaska, he returned to Oregon and, while working at the Ladd & Bush bank of Salem, began his study of politics. Asahel Bush, the founder of the bank, was also a journalist and established The Oregon Statesman in 1851. Bush was a Democrat steeped in state politics and introduced West to the party ideals. West was captivated.

“I gathered what little I know about the use of the English language; became imbued with the democracy of Jefferson and Jackson; discovered that God’s ‘chosen people’ were really those who voted the Democratic ticket —and voted it straight; was taught to believe that a public office was a public trust and that political dishonesty, waste and extravagance should not be tolerated,” he wrote. West campaigned for George E. Chamberlain in his second, successful gubernatorial campaign and was duly rewarded. “About a year after taking office, Governor Chamberlain, no doubt at the suggestion of Mr. Bush, asked me to accept the appointment of state land agent for the purpose of putting an end to the frauds of the old state school land ring.” The State Land Board was selling off unsurveyed school lands for $1.25 an acre. A buying frenzy led to rampant fraud and a federal investigation.

In 1905, West took the job for $150 a month and worked almost single-handedly, resorting to unconventional methods at times. Even though he was an ardent Prohibitionist, West made friends with an inside man and got him “soused to the neck” to secure “information that made possible the uncovering of some surprisingly crooked transactions” that included forgery, bribery and political corruption. West’s final report led to federal trials and convictions, and a recovery of 900,000 acres for the State of Oregon. West remained highly sensitive to the exploitation of natural resources, an attitude that eventually would shape his gubernatorial campaign platform as well as his effort to save Oregon’s beaches from privatization.

“The people of Oregon are fine, but damn particular. One often is obliged to resort to strategy in order to induce them to do the things that are really in their interest.” — Oswald West

West was appointed to State Railway, and eventually, he decided to run for governor due to a perceived lack of options. “Failing to find any other man of standing willing to enter the lists, and not wishing to give my support to some other two-by-four, I decided to throw my own hat in the ring,” West wrote.

After he “shoestringed it through the campaign” and received the “votes of the friends of the ‘Oregon system’ of government,” West was elected. West was 37 when he became governor, and by this time, had become adamantly opposed to the sale of coastal tidelands. The State Legislature was now in favor of privatization of these coastal lands. West ingeniously parlayed two central issues into one: building roads and saving the beaches.

“At the time I became governor in 1911, everybody was talking about good roads,” West wrote, “but no one was declaring his willingness to stand his share of the cost.” Another dilemma was West’s belief that making it illegal to buy coastal land would cause controversy and the legislature would be swamped with protests. In order to preserve the coast’s importance as a north-south transportation route, block further sales of the shoreline and address an overall lack of funds to build additional highways, West mulled a “bright idea.”

“I drafted a simple short bill declaring the seashore from the Washington line to the California line to be a public highway,” he wrote. “I pointed out that thus we would come into miles and miles of highway without cost to the taxpayer. The Legislature and the public took the bait—hook, line and sinker. Thus came public ownership of our beaches.”

On February 13, 1913, the Oregon Legislature passed West’s bill and designated the entire tideland on the ocean shore as a highway with “free and uninterrupted” public access from the Columbia River to the California line. West proclaimed that “no local selfish interest should be permitted, through politics or otherwise, to destroy or even impair this great birthright of our people.”

Few people understood the gravity of this bill, at least not then. “Os West was smarter than today’s politicians. He got the entire Oregon Coast virtually without notice or fanfare,” reporter Harold Hughes wrote in The Sunday Oregonian in 1967. “Newspapers of the day carried only tiny stories – and that’s the way Governor West planned it. The fighting governor got the beaches without a battle or a loud verbal shot being fired.”

President Theodore Roosevelt praised West’s efforts by stating, “In Governor West of Oregon, I found a man more intelligently alive to the beauty of nature … and more keenly appreciative of how much this natural beauty should mean to civilized mankind, than almost any other man I have ever met holding high political position.”

Oregon did not necessarily set an example in other states. Today, most coastlines are private. In fact, approximately 93 percent of Maine’s 4,000-mile shoreline is private property to the mean low water mark and about 75 percent of Massachusetts’ coastline is privately owned to the low tide line, according to nonprofit Surfrider. In Florida, 77 percent of the beaches are privately owned to the high tide mark and 58 percent of California’s coastline above mean high tide line is privately owned. In addition, about 60 percent of the tidelands are privately owned to variable tidal lines in Washington.

“Oregon is so lucky that its beaches are owned by the public,” says Pete Stauffer, the ocean ecosystem project manager for Surfrider. “In so many states it is not the case. Once the beaches are privatized, it is very difficult to get them back into the public domain.” Only Hawaii and Texas join Oregon in maintaining publicly-owned or controlled coastlines.

But Oregon was not finished fighting for its public beaches. The 1913 Os West legislation would ultimately be a precursor to a major showdown more than five decades later in Governor Tom McCall’s Beach Bill in 1967.

“West had always been popularly applauded for saving the beaches,” Kathy Straton wrote in her book Oregon’s Beaches: A Birthright Preserved. “Few persons were aware that his legislation, and subsequent amendments, applied only to the beach seaward of the ordinary high tide line. Most recreationalists did not realize that on some beaches they actually were using private land.”

Ground zero for the Beach Bill would be the Surfsand Motel in Cannon Beach, coincidentally only a few miles from West’s former log cabin home. In the summer of 1966, some Oregonians complained about the denial of public access to beach property at Surfsand Motel in the dry sand portion, or the land above the high tide on the beach. The motel owners were operating under the impression that they owned the land to the high tide mark and had been paying taxes on it.

McCall and others wrote and passed the Beach Bill, which designated the beach as extending up to the vegetation line for public use. The bill was later upheld in courts in 1972.

“I think the great difference between Governor West’s 1913 proclamation and the 1967 Oregon Beach Bill was the public’s massive awareness and interest,” says Tom Olsen, Jr., producer of the documentary, Politics of Sand. “This is in large part thanks to the press who made Oregonians aware of what was at stake.”

Although West worked under the radar of public awareness at times, he always worked in the public’s interest and would ultimately achieve much in his four-year term as a strong advocate of welfare, development and conservation measures. His accomplishments include administering tougher banking regulations, enacting a measure to protect people from purchasing fraudulent securities, reforming the railroad commission and expanding its responsibilities, modernizing budgeting policies for the state, instituting a minimum wage law and designing a workman’s compensation system as well as the Industrial Accident Commission. West set the stage for the development of the Oregon State Park System and advocated women’s rights, signing the equal suffrage amendment into the constitution in 1912. West also advocated for prison reform and influenced the creation of the Fish & Game and Highway Commissions.

Throughout his public service, Oregonians were amused by his dramatic stunts such as putting penitentiary inmates to work building roads and then single-handedly hunting down and capturing one prisoner who had escaped into the woods. Once, in a move to pass a bill to end the old state printing racket, West locked the Speaker of the Legislature in an office, although some accounts say a bathroom, to “permit someone to preside who was not so well informed nor so particular about the rules.” Perhaps the most notable stunt came when West rode a horse to Boise, Idaho for a meeting with Idaho’s governor because he had exhausted his expense account and couldn’t afford train fare.

In his short tenure, West emerged as a reform figure of progressive, populist politics in Oregon as a result of his espousal of direct participation in government through initiatives, referenda and direct primaries. West declined to run for re-election for he had “seen enacted practically all of the constructive legislation I had in mind” and harbored “no further desire to hold office.” Although he never served in a public office again, politics had gotten into his blood. “I was schooled to be a political ball player, and will die in the faith,” he wrote. Instead he went to law school and practiced in Portland, residing there until his death on Aug. 22, 1960.

Through West’s strong connection with people and genuine concern for their welfare, as well as his conservation-centric attitude, he turned the Oregon Coast into the people’s coast. His extraordinary vision is captured in his comment to a fellow crusader that, “The people of Oregon are fine, but damn peculiar. One often is obliged to resort to strategy in order to induce them to do the things that are really in their interest.”

Coastal Preservation Organizations

Surfrider is a nonprofit grassroots organization dedicated to the protection and enjoyment of the world’s oceans, waves and beaches. The Oregon Surfrider chapter focuses on a range of different volunteer programs, grassroots community projects, and public education that includes monitoring water quality, tracking shoreline development and beach accessibility and campaigning for the designation and protection of marine reserves. “We are the caretakers of West’s legacy, and we must ensure that the public’s rights are protected for future generations,” says Pete Stauffer, a Surfrider project manager. “The next step in the legacy is to secure lasting protection of the marine reserves.” surfrider.org

Another important organization is the Oregon Shores Conservation Coalition, created by Beach Bill proponents under Governor Tom McCall. Oregon Shores has three arms to the organization. The first arm is involved with enforcing land-use issues and applying laws such as the Clean Water Act to coastal management. The second is a volunteer program called CoastWatch where a volunteer “adopts” a mile of the coastline and monitors and observes the beach, reporting data to any number of agencies. Lastly, there is an ocean program that works in conjunction with other agencies to protect marine reserves. “It is not really one issue, but a new reality that refocuses and reshapes our work in many ways,” according to executive director Phillip Johnson. oregonshores.org

SOLV began under the inspiration of Gov. Tom Mc- Call and community leaders in 1969. Its chief aim is to restore natural spaces and provide educational opportunities to encourage environmental stewardship, providing resources to more than 250 Oregon communities annually. Twice a year SOLV organizes beach and river clean-ups, among other programs. solv.org

Things to Do at the Coast

The first step in planning an Oregon Coast getaway is as easy as visiting visittheoregoncoast.com. There are access points to the beach spaced approximately every three miles with plenty of campgrounds to choose from, many of which have both tent spots and yurts. Here are some suggestions to get you started ranging from north to south along the coast.

Astoria is the oldest settlement west of the Rockies dating back to 1805 and located at the base of the Columbia River. Its historical significance additionally rests on the fact that it is the western end of the Lewis & Clark trail. oldoregon.com

Fort Clatsop is where Lewis and Clark wintered over in 1805-1806 and is an authentic replication of their settlement, which includes exhibits and an interpretive center. nps.gov/lewi/planyourvisit/fortclatsop.htm

Cannon Beach has a happening downtown area and is home to the iconic Haystack Rock, a coastal landmark as well as a refuge to numerous sea birds and tide pools. cannonbeach.org

Tillamook produces nationally recognized cheese and offers tours of the factory. There is also good crabbing in the bay. This March Tillamook’s mild cheddar was named the best in the world at the World Championship Cheese contest in Madison, Wisconsin. tillamookcheese.com

Pacific City and Cape Kiwanda is one of the premier surf breaks and a good place for watching surfers from the relative safety of Pelican Brewery. Oswald West State Park is popular with surfers and hikers. oregonstateparks.org

Lincoln City is the venue for several annual summer and fall kite festivals as well as where beachcombers can look for any one of the 2,000 hand-crafted glass floats hidden on the beaches. oregoncoast.org

Depoe Bay’s Whale Watching Center offers some of the best viewing of the sixty-plus Gray whales that reside on the Central Coast in summer. whalespoken.org

Newport is home to the Oregon Coast Aquarium with an impressive underwater tunnel to see the large sharks, rockfish and stingrays circle above. aquarium.org. Newport also hosts a delectable seafood and wine festival every February as it has for the past thirty-three years. newportchamber.org

Cape Perpetua is an incredibly scenic spot along your Highway 101 journey with a great viewpoint of the coast, and the opportunity to hike down to tide pools or through an old-growth forest. A fissure in the basalt called Devils Churn is a fabulous spot to watch the waves crash against the rocks and to take photos.

The Sea Lion Caves, located 11 miles north of Florence, is worth a stop. Take an elevator that plunges 208 feet, or approximately twenty-one stories, into the world’s largest sea cave. sealioncaves.com

Florence is a hot spot for recreation—namely longboarding or offroad ATV-riding at the Oregon Dunes National Recreation Area. There are also numerous horseback riding opportunities with access points outside of Florence in order to bring your horses over or hitch a ride with C&M Stables. florencechamber.com

Bandon hosts a nationally-recognized golf course. Truly one of Oregon’s best courses. bandondunesgolf.com

Amble around the lesser-visited Port Orford, a quaint artist community worthy of a stop. discoverportorford.com

In Gold Beach, you can take a jetboat up the Rogue River, one of Oregon’s most famous rivers. There is excellent fishing farther upstream in the motorless Wild and Scenic section. goldbeach.org

Historic Lighthouses (north to south): Cape Disappointment, Tillamook Rock, Cape Meares, Yaquina Head, Yaquina Bay, Heceta Head, Umpqua River, Cape Arago, Coquille River, Cape Blanco.