In one corner, weighing in at five grams, the reigning champion of wine bottle enclosures, the queen of mean, the matriarch of winedom—it’s CORK (cue throngs of screaming fans). In the other corner, weighing in at almost nothing, the aluminum avenger, the whirling dervish of stoppers, it’s the one and only SCREW CAP (cue more screaming fans). The battle is on, and the victor is anyone’s guess.

Screw caps came into existence when people started speaking out against the number of “bad” bottles popping up. For the sake of this discussion, let’s define a “bad” bottle as one that has been infected with Trichloroanisole (TCA). A mouthful both literally and figuratively, TCA is a chemical compound that expresses itself as a flaw in the wine. Infected wines are sometimes referenced in terms such as corked, corkiness or cork taint. The resulting wine can smell and taste dirty, musty and/or dank. TCA commonly makes its way into wine through naturally porous corks. That susceptible membrane was the genesis for airtight, aluminum-based screw cap closures.

Fear not, wine lovers, TCA won’t hurt you; it just doesn’t taste very good. Proponents of cork argue that flaws still occur in wines with screw cap closures since wines can sometimes be affected by TCA before bottling, specifically in the barrel. Another flaw that is a possibility regardless of capping style is overrunning of the yeast Brettanomyces.

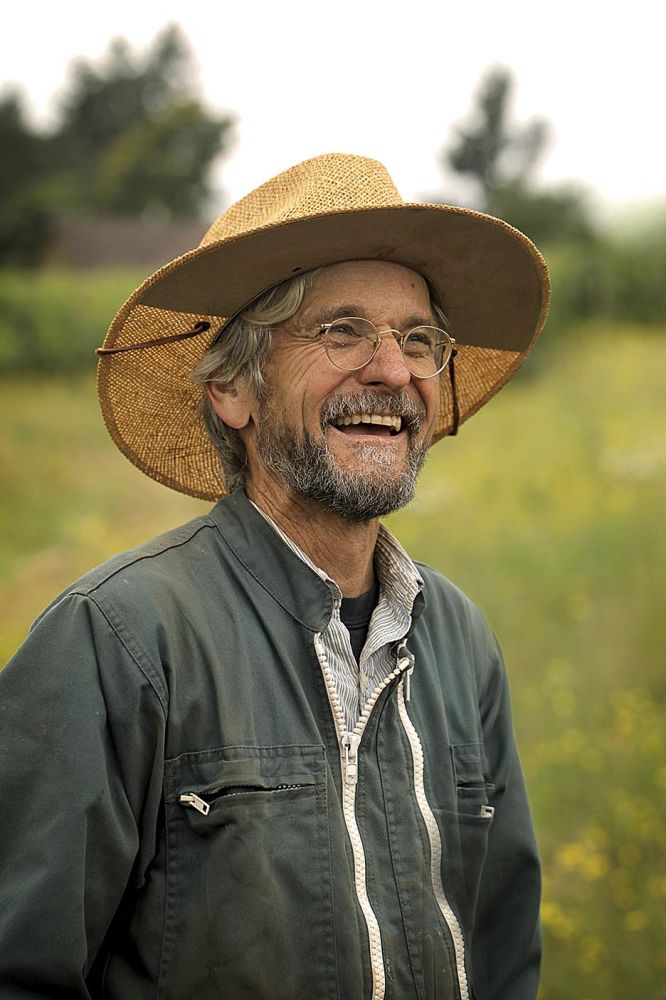

John Paul, winemaker and founder of Cameron winery in Dundee, incorporates only cork for his wine. He feels that the long-term ability of screw caps to both protect the wine and allow it to age gracefully have yet to be proven. “Early returns on the subject show wines that simply do not mature the same, or at the same rate as those in cork enclosed bottles,” says Paul. “There are lots of questions that I have, such as: What might be leaching into the wine from the enclosure?”

Harry Peterson-Nedry, founder and winemaker for Chehalem Winery in Newberg, has been using screw caps on a selection of his wines since 2003, and on all bottles since 2008. “The incidence of cork taint is very high and, although we’d like to use a naturally derived closure like cork, the tradeoff is not sustainable for our customers,” says Peterson-Nedry, who tracked the number of cork taint-affected bottles to around five to ten percent. “No other industry would put up with that rate of defective product,” he continues.

Dustin Mowe is president of Portocork America—a business that has been specializing in the sale of natural cork to wineries for over twenty-five years—feely admits that the cork business has been both difficult and exciting over the last several years. The introduction of synthetic closures into the market in 1992 gave winemakers options besides cork. An industry that once had exclusive hold on the market was suddenly faced with competition. “The cork industry had to react with scientific initiatives, says Mowe. “The producers who didn’t want to change and implement quality-first procurement methods fell by the wayside.” The change cut the cork industry from two thousand cork producers in Portugal (where most cork trees are grown) to one thousand, and from thirty to fifteen in the United States.

To increase the quality of cork products and find a way to be more competitive with their new rival, cork producers implemented changes, testing methods, and systematic cleansing methods to put cleaner cork on the market. “Since doing this, we have seen a continuous improvement in the cork quality,” says Mowe. (see graph)

For Mowe, the industry is about accountability and diligence. Portocork routinely checks the quality of their products, and it shows. “I am told time and time again by our customers that the occurrence of problems because of our cork is less than one-half of one percent,” says Mowe. He also took the opportunity to squash rumors that cork trees are now harder to come by, hinting that those rumors may have been started by “alternative closure” industry advocates attempting to increase the spotlight on their young product.

In reality, there is not a perfect wine closure. However, producers of corks, screw caps and other alternative cappings continue to investigate ways to improve the quality, durability, and reliability of their products. Until then…the fight goes on and the champion is yet to be crowned.

Thank you for the informative article. Regarding Mr. Peterson-Nedry's comments on cork taint percentages, I would ask that Mr. Perterson-Nedry provide quantifiable and scientific research that proves 5 to 10% of wines being "off" due to only natural cork/TCA taint. As a wine maker I'm sure he's aware that there are over 800 chemical compounds that can affect the favor profile of wine and of those 800, none of them are caused by natural cork. Also, it has been scientifically proven that if a winery has TCA present,i.e. in the walls, flooring ,pallets, cardboard or boxes the wine can be affected by TCA whether a natural cork, screw cap or plastic plug is used to seal the wine. Regarding his comment that, “No other industry would put up with that rate of defective product,”, that's just not accurate. A 2005 FDA study on spoilage and loss in agricultural products, showed the loss rate for apples alone, to be close to 40%. The losses were tracked from farmer to wholesaler to retail and then to consumer. In closing Peter Gago, head winemaker at Penfold’s, admitted during an event after the 2012 London International Wine Fair, that levels of TCA in his wines were down to 1%, or, he explained, the same percentage that are prematurely oxidised due to mechanical damage to screwcaps.” It is important to give consumers real fact's not outdated and unsubstantiated rumors. Possibly the next time this topic comes up for an article, it can focus on the environmental cost of screwcap and plastic closures. I venture to say, no winemaker wants a Bauxite mine or oil refinery across from their vineyard.

Best,

Patrick Spencer

Executive Director

Cork Forest Conservation Alliance