written by Kevin Max

Long before they came back in smaller craft, the Spanish, the English and the French hoisted sails in the names of their crowns and pulled up the windy Columbia Gorge. Explorers first, they admired the sheer basalt cliffs, the towering pines and the plunging falls along her banks. As sailors, though, they took note of the strong wind in the Gorge.

Today, the same wind that Capt. Robert Gray first encountered on a maiden voyage up the Columbia in 1792 blows in sailors from around the globe to compete in world championship races hosted by the Columbia Gorge Racing Association (CGRA). Brits, Danes, Aussies, Japanese and American sailors command smaller boats in international races launched from Cascade Locks, twenty miles downriver from Hood River.

“Ultimately, I could see Cascade Locks become to dinghy sailing what Hood River is to windsurfing.” Bill Symes projects. “Dinghy sailing is not as big as windsurfing, but it’s big enough to have an economic impact on Cascade Locks.”

“In the Gorge, you get fifteen to twenty mile-an-hour winds in the summer, and that’s ideal for sailing,” says Bill Symes, longtime sailor and president of CGRA, an all-volunteer nonprofit organization.

Cascade Locks—known more for a recently failed Gorge casino gambit and ongoing controversy over the proposed site of a Nestlé water-bottling operation—decades ago became the curiosity of Kerry Poe, a competitive sailor from Portland and founder of CGRA.

As a young newspaper delivery boy, Poe once clipped a photograph of a sailboat. That image fueled his imagination. In sixth grade, he joined the Willamette Sailing Club. There he learned how to handle dinghies, small craft that are the mainstay of any sailor’s education.

He became more and more competitive and soon bought his first vehicle—a sunfish sailboat. This passion stayed with him, and the newspaper boy with an inspirational cut-out was soon racing for the U.S. Sailing Team, specializing in the international 470 class, named for its hull length in centimeters.

By 1990, Poe and his sailing partner, Chris Bittner, had surged to the top of the 470 Olympic class and won the Pacific Coast Championships that year. As part of that race’s tradition, however, the winners were required to host the next championship on their home surf. At this point, Oregon was equipped to host track and field championships, mountain biking championships, lumberjacking and beer drinking championships—but at first glance, it didn’t seem to be a feasible spot for one of sailing’s top competitions.

Bittner and Poe had sailed and trained in the Columbia River Gorge— even racing against friends in makeshift “bush regattas.” By then, the Gorge was already known for fierce winds that blew into the Hood River area and launched a windsurfing mecca. Dinghy sailing, however, requires a different wind, a gentler wind. Poe and Bittner scoured and sailed the Gorge for months, methodically testing different sites for the best wind.

Their search ended in the small town of Cascade Locks, where nearly 75 percent of its seventy-five K-6 students are on free or reduced lunches. There wasn’t much to report in terms of infrastructure, just a tiny riverfront gravel parking lot from which participants could launch their small craft. There was no building to conduct race administration, nor were there bathrooms. There was no yacht club to change clothes and refuel. But there was wind—the most crucial element with which Poe and others would build an internationally-recognized sailing venue.

The next year saw Oregon’s first sailing championships from Cascade Locks. “People loved it,” says Poe. “The following year, word spread and people called me and were asking about sailing in Cascade Locks. The International 14s Championships came in 1992, and they’ve been back every year.” Soon sailboats in national and international championships were skipping downwind from Cascade Locks in what was becoming the place to race in North America. Competitors came in pairs, in Tasars and 29ers. Solo sailors hiked out in their Lasers and flitted above the water in their Moths. No matter what class of boat they sailed, they came to do it in regattas held by the Columbia Gorge Racing Association.

Otto Strandvik, a Danish sailor who has competed in several races in the Gorge, says it’s the constant, reliable wind that makes Cascade Locks perfect for racing. “There are only a few places in the world like that.”

Luke Parker, an Australian sailor, came to Cascade Locks for the first time to compete in the Laser World Championships last summer. He has raced in many venues around the world. It was his sister, a five-time Olympic sailor, who told him about sailing in the Gorge. “With racing in the Gorge, there’s the people infrastructure,” notes Parker. “The Gorge has no physical infrastructure but a great bunch of volunteers and, to me, that’s the joy of it.”

Two-time Olympic sailing medalist, Charlie McKee, started training in Cascade Locks in the ’80s and continues to train there. “What makes it special for sailing is that it’s not as windy as other spots in the Gorge, and it’s off the beaten path,” he says. “All the things that make it not as good for windsurfing make it great for sailing.”

Lindsay Bergan, a competitive sailor from Seattle, describes the Gorge as having optimal sailing conditions. Bergan competes in the Moth and Tasar classes and trains or races in Cascade Locks at least three times each summer. Compared to many other sailing venues where she’s competed, she says, the Gorge is so clean.

This year, CGRA will host nineteen events between April and September, including five national championships in four different classes. These days, it’s the high demand for the wind at Cascade Locks that has the small sailing organization looking for resources to expand while seeking common ground with the economically struggling town.

“Our long-term goal is to see a top-notch sailing facility in the Gorge,” says Symes. “It’s a world class venue, and we’re supporting it on a shoestring budget.”

While Symes notes that some locals see the boats and sailing organization as an intrusion on their waterfront, others appreciate the new business that might otherwise play out in Hood River.

Last year, The Resort at Skamania Coves, a collection of luxury houses across the river from Cascade Locks, hosted many sailors from various races put on by CGRA. Co-owner and sailor, Scott Lonsway, estimates that 30 to 35 percent of his business comes from sailors competing in races at Cascade Locks. While the collapse of the Gorge casino proposal took the wind from the sails of local small businesses, the Moth World Championships last season, he says, really put Cascade Locks on the map.

“Ultimately I could see Cascade Locks become to dinghy sailing what Hood River is to windsurfing,” Symes projects. “Dinghy sailing is not as big as windsurfing, but it’s big enough to have an economic impact on Cascade Locks.”

How to Watch Sailboat Races

What Types of Sailboats Race?

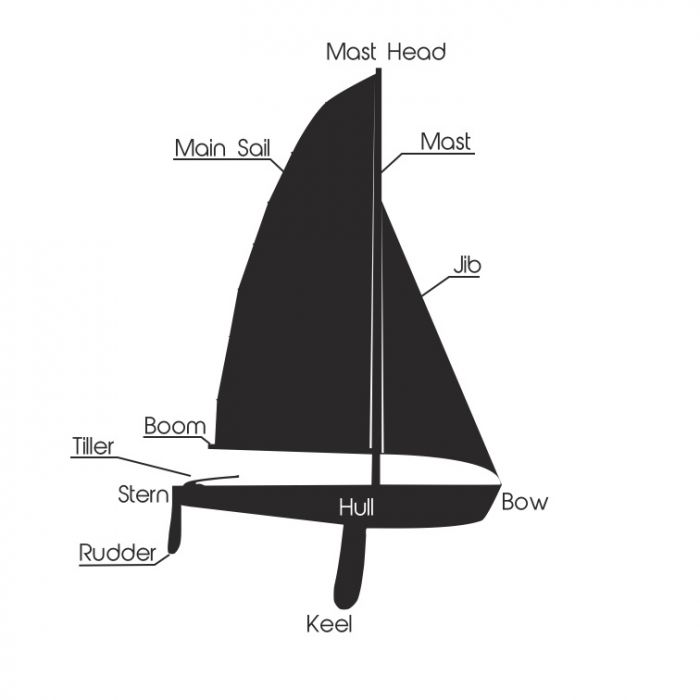

Small sailboats usually race as one-design classes, where all the boats in the race are identical in size and shape. About a dozen of these classes sail regularly in the Gorge, ranging from 8-foot Optimist Prams to 24-foot Melges 24s. CGRA regularly holds national and international championships for the world’s most competitive classes, including the Laser (Olympic men’s and women’s single-handed class), the 49er (Olympic men’s double-handed skiff class), and the International Moth Class, an 11-ft development class that sails on hydrofoils at speeds up to 30 mph.

What Does The Course Look Like?

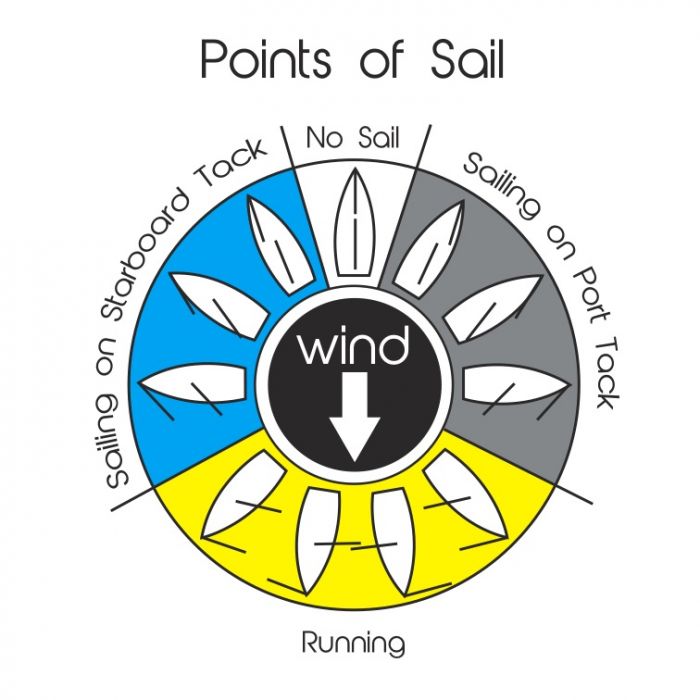

The race course is typically laid out parallel to the wind direction, with the first turning mark set directly upwind about a half mile to one mile from the start line. Since sailboats cannot sail directly into the wind, they must zigzag (tack) at 90 degree angles up the first leg to the windward mark. After rounding the windward mark, they sail with the wind behind them to a second turning mark set directly downwind. This is the leg where many classes break out the large, colorful sails called spinnakers that billow out in front of the boats. After rounding the downwind, or leeward, mark, the boats turn upwind again to tack to the finish line (often the same as the start line). There are many variations on the basic windward/leeward course, including multiple laps, a third turning mark set between the windward and leeward marks and off to the side to create a triangular course, and separate start and finish lines.

How Long Does It Typically Take For Boats To Complete The Course?

The races can be as short as twenty minutes or as long as an hour or more, depending on the size of the boats and the wind. A regatta consists of several races, usually five to ten. Competitors are ranked according to their cumulative score for races sailed. The sailor with the lowest score wins.

What Are The Strategies On The Water?

• Use shifts in wind direction to sail the shortest course to the next mark

• Find the most favorable current to sail in

• Maintain clear wind (nobody blocking)

• Cover your opponents to slow them down and prevent them from passing

What Constitutes Good Sailing?

• Sails correctly trimmed to conform to the current wind direction and course

• Knowing and complying with the racing rules of sailing to avoid penalties for hitting or fouling right-of-way boats

• Crew leaning out (hiking) to keep the boat from heeling too much; flat is fast

• Avoiding capsize—upside down is slow!

What Is The Best Vantage Point For Watching The Race?

Unlike most sailing venues where the action takes place far from shore, CGRA races are set in a natural amphitheater. Spectators can get a great view of the racing from bleachers on the point at Cascade Locks Marine Park, about 100 yards from the windward mark.